Japanese

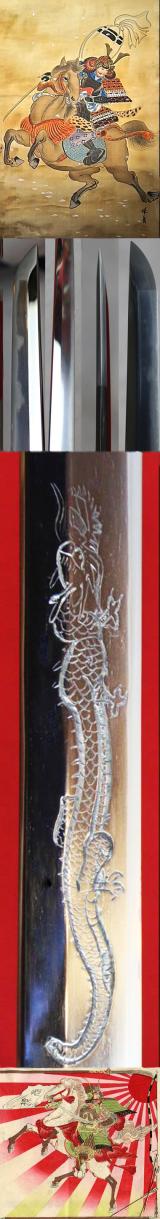

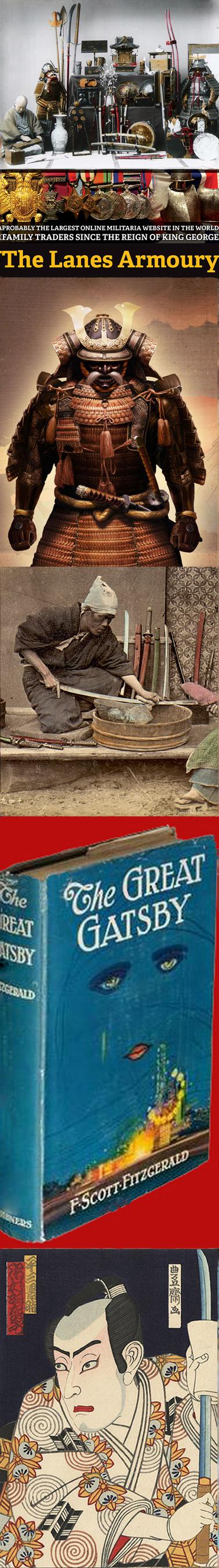

A Stunning, Antique, Edo Period Circa 1660 'Dragon Horimono' Shinto Horseman's Katana. With A Carved Horimono Blade of a Dragon. With a Superb Suguha Hamon That Transforms With Choji Elements At The Top Section

A very impressive, beautiful and substantial original katana of a horseman samurai, that has both incredible beauty, yet conveys a considerable sense of power through its length and heft. From the Shinto period likely from 1640 to around 1680-1700. All the koshirae and the blade are in super condition for age.

A large iron plate mokko tsuba with mimi, decorated with a village scene with gold highlights. the fuchi kashira are matching with a rattan screen pattern showing gold decorated blooms. a superb black isheme stone finish saya, and finest black tsukaito binding wrapped over fine menuki, and traditional samegawa {giant rayskin}.

Horimono, a type of carving, often adds other decorative Horimono to the blade in addition to grooves. The properties of horimono are usually traditional images, such as swords, dragons, deities, Buddhist patterns, bonji, Chinese characters, and so on.Among the blades of the Koto period of sword manufacture (1600), many of the carvings display religious meaning: Bonji (sanskrit), Su-ken, Fudo Myo-o,Kurikara, Sanko-tsuki-ken, Goma-bashi, Hachiman-daibosatsu, Namu-myoho-renge-kyo, and Sanjuban-shin.In the Shinto period of swordmaking (1600), the carvings become more decorative with depictions of cranes and turtles, ascending and descending dragons, shochikubai (pine, bamboo and plum), and the deity of wealth, Daikoku.These images are carved with hammers hitting small chisels of various sizes. The internal surface of horimono is ground smoothly and finely, and polished during the polishing process. Making horimono is both difficult and time-consuming; Swordsmiths mostly carve grooves and simple Sanskrit characters themselves, while the more magnificent horimono is made by specialized craftsmen. After deciding which image to use, carefully draw a detailed pattern with a brush at the position to be carved, and then complete the horimono. The ideal horimono has a moderate proportion, the size matches the word to be carved, and is engraved in the appropriate position

The decorative horimono were introduced during the Edo period on the katanas and are generally larger than the votive ones. They often depict a dragon, taking up traditional iconography but using superfine techniques to embellish the blade.

The blade is in super condition for age with just a few very small thin natural age surface marks. See photo 3, on the far right hand blade picture in the photo group read more

7450.00 GBP

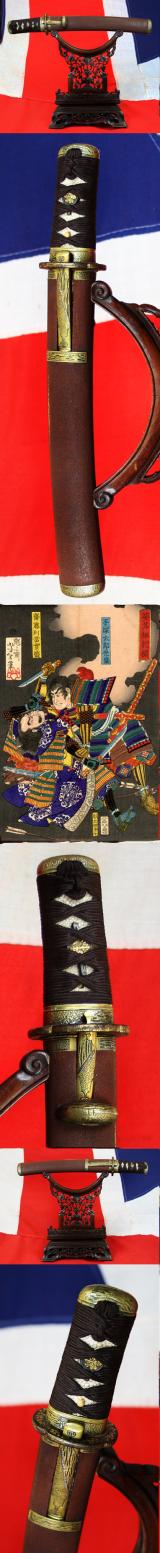

A Truly Beautiful Antique Koto Period, 'Dragon Head' Hamon, Unokubi (鵜首) Zukuri Blade Tantō. In a Chesnut and Sable Livery, Matsushiro Sinano Koshirae With Kozuka and Kogai, with Higo Scool Tsuba Inlaid With Pure Gold Sakura {Cherry Blossom}

Mounted with a fully matching suite of sinchu and contrasting silver line mounts, including the kozuka and kogai of the fine Matsushiro Sinano school. The Edo period iron tettsu Higo school tsuba is inlaid with pure gold cherry blossom. A very similar Higo school tsuba can be seen in the Osafune sword Museum in Japan, mounted upon a Tomonari, Sukesada blade tanto sword.

The kozuka and kogai pockets in the saya are lined with delicate, doe skin, decorated with a black and red pattern, on a natural white skin ground, in the same form as can see seen to embellish kabuto and armour {see photo 8 in the gallery}.

Wonderful chessnut brown ishime stone finish lacquer saya, with a contrast of sable brown tuskaito silk binding, wrapped over pure gold kiri mon menuki, on shakudo bar ground, over traditional samegawa {giant rayskin}.

The stunning blade has a beautiful intricate hamon, including, where the yakiba meets the hada the detailed head of a dragon. A very small combat surface mark to one side of the blade, likely made by a blade tip {see both detailed in photo 10}.

Unokubi (鵜首): An uncommon tantō style akin to the kanmuri-otoshi, with a back that grows abruptly thinner around the middle of the blade; however, the unokubi zukuri regains its thickness just before the point. There is normally a short, wide groove {hi} extending to the midway point on the blade, this is a most unusual form of unokubi zukuri blade tanto without a hi.

Historically significant and intricately crafted, Japanese swords offer a unique glimpse into Japanese society. Compared to traditional Japanese blades, the Tanto stands out for its beauty, adaptability, and rich cultural importance. But of course, not everyone is well-familiar with this samurai sword form. Despite being traditional dagger sized all Japanese blades are titled as swords however short they may be.

The Matsushiro Shinano Koshirae is a distinctive style of antique Japanese sword mounting (koshirae) that originated in the Matsushiro domain of Shinano Province (present-day Nagano Prefecture) during the Edo period. This style is specifically characterized by the use of brass (shinchu) for all of its metal fittings.

Key Characteristics

The defining feature is the uniform use of brass for all components of the sword furniture, including the fuchi (hilt collar), kashira (pommel), tsuba (handguard), kojiri (scabbard tip), kozuka (small utility knife handle), and kogai (spike).

These fittings often feature intricate decorations, such as bamboo or other natural patterns, sometimes with silver striping or designs.

Matsushiro was a castle town developed by the Sanada family in the early Edo period. It is believed that many domains developed their own distinct styles of koshirae during this era, and the Matsushiro koshirae was a local specialty.

The koshirae was the ornate, functional exterior of a samurai's sword, designed for both aesthetic appeal and practical use, in contrast to the plain wooden shirasaya used for storage.

Swords with original Matsushiro koshirae are considered unique historical artifacts and are highly valued by collectors for their complete, matching sets of fittings.

For example one of the great tanto swords of samurai history is “Tanto Mei Bishu Osafune Jyu Nagayoshi” (短刀 銘 備州長船住長義) it is a tanto made by the swordsmith “Osafune Nagayoshi” (Osafune Nagayoshi / Chogi) who was active in Bizen Province (currently eastern Okayama Prefecture) during the Nanbokucho period. This tanto was a favorite of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and later it was received by Toyotomi’s retainer “Maeda Toshiie” at Osaka Castle (Osaka Castle), and since then it has been handed down to the Maeda family of Kaga Domain, making it a prestigious famous sword.

The swordsmith, Osafune Nagayoshi, is one of the “Osafune Four Heavenly Kings” representing the “Osafune School”, a group of swordsmiths that flourished in Bizen Province, and is also listed among the “Masamune Jittei” (Masamune’s Ten Disciples), the ten high disciples of the swordsmith Masamune, who is called the “Ancestor of the Revival of Japanese Swords”.

Photo in the gallery of a Tanto sword, by Sadamune, Kamakura period, 1300s AD - Tokyo National Museum - Ueno Park, Tokyo, Japan. This shows how their samurai swords are displayed in the greatest Japanese museum in Tokyo. The koshirae {fittings} are always shown separately, if at all.

The antique Chinese display stand the tanto is shown upon is a superb hand carved hongmu hardwood piece, Ching Dynasty, and originally displayed a piece of the of finest Chinese Imperial Jade once featured in a Mandarin's palace in Peking, and you will see it featured throughout our online Japanese sword gallery to display wakazashi and tanto. It isn't for sale as it has been used by the family in our gallery for around 100 years.

Over the centuries some extraodinarily talented bladesmiths have integrated within their blades a form of identfiable mark, one smith creates rabbit ears in his hamon, several others feature the profile of Mount Fuji, and even one features Mount Fuji with birds flying over head. This smith has created a dragon's head into his hamon, with utterly remarkable skill. It is possible you may never ever see another surviving example.

Overall 13.5 inches long, blade 8.25 inches long tip to tsuba. read more

4950.00 GBP

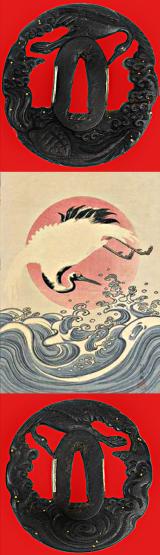

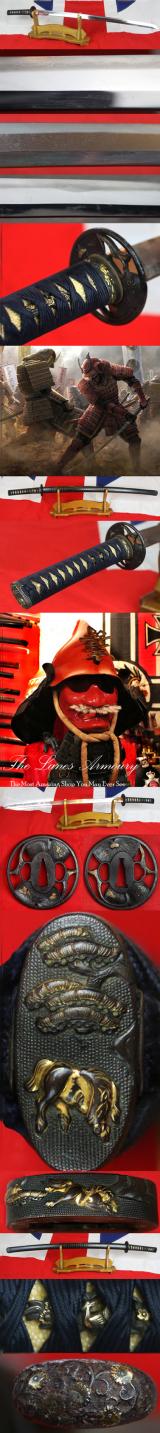

A Beautiful Omori School Tsuba Turbulant Sea With Crashing Waves and A Crane Swooping Over Turtle Below.. Edo Period

The crane and the turtle have a significant position in Japanese folk lore and tradition, as both symbolically represent longevity in Japanese art.

The shibuichi tsuba of marugata shape, with a kozuka and kogai hitsu-ana, the nakago-ana with some suaka sekigane, finely worked takabori and takazogan to depict breaking waves carved in the typical manner of the Omori school with inlaid gold spray drops. Sekigane. Late 18th century, Edo period (1615-1868)

Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other.

A closely related shibuichi tsuba with waves {omitting the crane and turtle} by Omori Teruhide is in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, accession number 11.5454.

Koryūsai Isoda, woodblock print, of a crane flying over crashing waves.

64mm read more

625.00 GBP

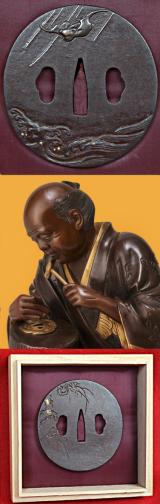

A Beautiful & Stunning Edo Period Tetsu Round Tsuba Of a Bat Flying in Rain Over Turbulant Seas.

The reverse is a willow carved in sunken relief, all upon a russet ground. somewhat reminiscent of the work my master Kenzui,

In Japanese folklore, bats are often associated with good luck and prosperity. One popular folktale is the story of "Bakeneko," a mythical creature resembling a cat with bat-like features. Bakeneko is believed to bring blessings and protection to households, particularly during times of hardship.

In the context of kimono designs, the depiction of bats holds specific symbolism. Bats are often featured alongside other auspicious motifs such as the pine, bamboo, and plum—traditional symbols of longevity, resilience, and prosperity. When bats are included in these designs, they reinforce the notion of good fortune and longevity, making them popular motifs for celebratory occasions such as weddings and New Year's festivities.

During the Meiji period (1868-1912), Japan underwent significant cultural and societal transformations. Bats continued to be prominent symbols during this era, often depicted in art and textiles as representations of prosperity and modernisation. As Japan embraced Western influences and embarked on industrialisation, the symbolism of bats evolved to reflect aspirations for economic growth and social advancement. Bats were frequently incorporated into decorative arts, such as ceramics and textiles, to convey wishes for prosperity and success in the changing landscape of Meiji Japan.

72mm read more

895.00 GBP

A Good Yoshii School Wakazashi, Likely Muromachi, Signed Yoshii Mitsunori Dressed With A Stunning Livery of Brown Ishime Lacquer Complimented With a Finest Blue Silk Tsukaito Hilt Wrap

A good, antique, wakazashi signed Yoshii Mitsunori.

Beautiful blue-green tsuka-ito wrap over a pair of feather form menuki, traditional samegawa {giant rayskin}. Higo school iron kashira decorated with a large leaved plant on a plain course plain background. plain iron fuchi.

Very attractive Edo period round plate tetsu tsuba, reminiscent of the Yokoya School, with pronounced mimi rim, engraved with katakiri and kebori on one side with Mount Fuji, and a deeply engraved shishi lion dog.

The Yoshii (吉井派)school was active in Yoshii, near Osafune, beginning in the Nanbokuchô period 1336-1392. Tamenori (為則) is said to have been the founder, followed by Kagenori (景則), Sanenori (真則), Ujinori (氏則), Yoshinori (吉則), Mitsunori, (光則), Morinori (盛則), Naganori, (永則) , Kanenori (兼則), and others. Later generations of smiths used the same names and those who moved to Izumo province are known as the Unshu Yoshii (雲州吉井)smiths.

Most of the Yoshii (吉井)blades were produced during the Muromachi {室町時代,} era, 1336 to 1573.This wakazashi was made during this era.

Their workmanship shows its own distinctive traits and is an unorthodox variation of the Bizen tradition.

By the end of the Muromachi period, the first Europeans had arrived. The Portuguese landed in Tanegashima south of Kyūshū in 1543 and within two years were making regular port calls, initiating the century-long Nanban trade period. In 1551, the Navarrese Roman Catholic missionary Francis Xavier was one of the first Westerners who visited Japan. Francis described Japan as follows:

"Japan is a very large empire entirely composed of islands. One language is spoken throughout, not very difficult to learn. This country was discovered by the Portuguese eight or nine years ago. The Japanese are very ambitious of honors and distinctions, and think themselves superior to all nations in military glory and valor. They prize and honor all that has to do with war, and all such things, and there is nothing of which they are so proud as of weapons adorned with gold and silver. They always wear swords and daggers both in and out of the house, and when they go to sleep they hang them at the bed's head. In short, they value arms more than any people I have ever seen. They are excellent archers, and usually fight on foot, though there is no lack of horses in the country. They are very polite to each other, but not to foreigners, whom they utterly despise. They spend their means on arms, bodily adornment, and on a number of attendants, and do not in the least care to save money. They are, in short, a very warlike people, and engaged in continual wars among themselves; the most powerful in arms bearing the most extensive sway. They have all one sovereign, although for one hundred and fifty years past the princes have ceased to obey him, and this is the cause of their perpetual feuds."

This sword has certainly seen combat in its centuries long combat life, the external koshirae are excellent, after being refurbished in the last 20 years, the blade is beautifully bright and elegant with natural age wear for a blade so old, with surface thinning. read more

2995.00 GBP

A Superb, Original, Antique Japanese Shinshinto Period, 19th Century, Samurai's, Secret, Hidden Fan-Dagger, A Kanmuri-Otoshi Form Kakushi Ken

A fantastic original antique samurai conversation piece, a samurai tanto {dagger} disguised as a folded fan, that the blade is concealed within. A wide and very attractive kanmuri-otoshi form kakushi ken, with clip back return false edge, overall bright polish and just the faintest traces of miniscule old age pitting. Edo period secret bladed tanto,19th century, with carved wood and bi-colour urushi lacquered fittings, in ishime black and golden yellow, beautifully simulated to look like a traditional Japanese folded fan.

A photo in the gallery from Edo Japan of a seated high ranking samurai holding his tachi and war fan. Another samurai standing also with fan and daisho through his obi. Samurai sometimes disguised their blades as inoffensive items, such as cleverly made walking sticks or other common objects such as fans. Their ancestors, the classical warriors, overlooked nothing which could be used as a weapon. Also, deprived of their swords by law in the Meji era, late 19th century samurai had to rely even more on their own ingenuity and resourcefulness for protection against thieves, hoodlums, bandits and intrigue. The blade nakago sealed in place, so there was no telltale visible mekugi blade affixing peg.

A Japanese war fan is a fan designed for use in warfare. Several types of war fans were used by the samurai class of feudal Japan and each had a different look and purpose. One particularly famous legend involving war fans concerns a direct confrontation between Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin at the fourth battle of Kawanakajima. Kenshin burst into Shingen's command tent on horseback, having broken through his entire army, and attacked; his sword was deflected by Shingen's war fan. It is not clear whether Shingen parried with a tessen, a dansen uchiwa, or some other form of fan. Nevertheless, it was quite rare for commanders to fight directly, and especially for a general to defend himself so effectively when taken so off-guard.

Minamoto no Yoshitsune is said to have defeated the great warrior monk Saito Musashibo Benkei with a tessen.

Araki Murashige is said to have used a tessen to save his life when the great warlord Oda Nobunaga sought to assassinate him. Araki was invited before Nobunaga, and was stripped of his swords at the entrance to the mansion, as was customary. When he performed the customary bowing at the threshold, Nobunaga intended to have the room's sliding doors slammed shut onto Araki's neck, killing him. However, Araki supposedly placed his tessen in the grooves in the floor, blocking the doors from closing. Types of Japanese war fans;

Gunsen were folding fans used by the average warriors to cool themselves off. They were made of wood, bronze, brass or a similar metal for the inner spokes, and often used thin iron or other metals for the outer spokes or cover, making them lightweight but strong. Warriors would hang their fans from a variety of places, most typically from the belt or the breastplate, though the latter often impeded the use of a sword or a bow.

Tessen were folding fans with outer spokes made of heavy plates of iron which were designed to look like normal, harmless folding fans or solid clubs shaped to look like a closed fan. Samurai could take these to places where swords or other overt weapons were not allowed, and some swordsmanship schools included training in the use of the tessen as a weapon. The tessen was also used for fending off knives and darts, as a throwing weapon, and as an aid in swimming.

Gunbai (Gumbai), Gunpai (Gumpai) or dansen uchiwa were large solid open fans that could be solid iron, metal with wooden core, or solid wood, which were carried by high-ranking officers. They were supposedly used to ward off arrows, as a sunshade, and to signal to troops.

12 inches long overall. approx 7.5 inch blade. The black ishime lacquer is near pristine, the golden yellow urushi lacquer has some natural, dark, handling age staining. read more

1320.00 GBP

The Lanes Armoury, Often Referred As Britain’s Favourite Antique Gallery. Family Traders, For Many Generations In The Lanes Over 100 Years & 200 Years As General Merchants In Brighton. We Are Also Europe’s Leading Original Samurai Sword Specialists

another fantastic collection of original samurai swords have just arrive, ready for cleaning and conservation.

We are the leading and pre-eminent original samurai sword specialists in the whole of Europe, in fact, we know of no other specialists outside of Japan, and likely within it, that stock anywhere near the quantity of our original selection. Constantly striving to achieve the very best for all our clients from around the world, our solution demanded a holistic approach and a strategic vision of what can be achieved. A solution that has effectively taken over 100 years in the making, and thus in order to be improved upon, it is evolving, constantly. However, never forgetting our old fashioned values of a personal, one to one service, dedicated for the benefit of our customers.

We even had the enormous privilege, to own and sell, although, sadly, only very briefly, thanks to the kind assistance of the most highly esteemed Japanese sword expert in England, Victor Harris, an incredibly rare and unique sword, an original, Edo period, traditionally hand made representation facsimile of the most famous Japanese sword in world history, the Japanese National Treasure, Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi (草薙の剣). It is a legendary Japanese sword and one of three Imperial Regalia of Japan. It was originally called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi (天叢雲剣, "Heavenly Sword of Gathering Clouds"), but its name was later changed to the more popular Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi ("Grass-Cutting Sword"). In folklore, the sword represents the virtue of valour. Victor stated it was the only example he had ever seen, possibly an official Imperial commission, to create for the emperor and scholars a faithful, identical facsimile of the most treasured sword ever made in Japan’s history. The National Treasure sword is used only during the coronation of the Emperor, yet even the emperor is not permitted to gaze upon it {apparently} only to place his hand upon it, beneath its ceremonial silk cloth.

Our one time late advisor, Victor Harris, was Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities, at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, of the Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords. We fondly remember many brainstorming sessions on our ever expanding collection of ancient antique and vintage Japanese swords with Victor, and our late esteemed colleague, Chris Fox, formerly a member of the Nihonto of Great Britain Association, here in our store.

After well over 54 years of personal experience as a professional dealer by Mark, since 1971, and David’s experiance over 44 years, we are now universally recognised as Europe’s leading samurai sword specialists, with many hundreds of swords to view and buy online 24/7, or, within our store, on a personal visit, 6 days a week. In fact we know of no better and varied original samurai sword selection for sale under one roof outside of Japan, or probably, even within it. Hundreds of original pieces up to 800 years old. Whether we are selling to our clients representing museums around the globe, the world’s leading collectors, or simply a first time buyer, we offer our advice and guidance in order to assist the next custodian of a fine historical Japanese sword, to make the very best, and entirely holistic choice combination, of a sword, its history, and its {koshirae} fittings.

But that of course is just one small part of the story and history of The Lanes Armoury, and the Hawkins brothers, as the world famous arms armour, militaria & book merchants

Both of the partners of the company have spent literally all of their lives surrounded by objects of history, trained, almost since birth in the arts, antiques and militaria. Supervised and mentored, first by their grandfathers, then their father, who left the RAF sometime after the war, to become one of the leading antique exporters and dealers in the entire world. Selling, around the globe, through our network of numerous shops, warehouses, and antique export companies, in today’s equivalent, hundreds of millions of pounds of our antiques and works of art. Our family have traded as general merchants for over 200 years in Brighton, including supplying the Prince Regent {King George IVth} shellfish to his palace in Brighton, The Royal Pavilion.

Both Mark and David were incredibly fortunate to be mentored by some of the world’s leading experts within their fields of antiques and militaria. For example, just to mention two of Mark’s diverse mentors, one was Edward ‘Ted’ Dale, who was one of Britain's most highly respected and leading experts on antiques in his day. He was chief auctioneer and managing director in the 1960’s and 70’s of Bonhams Auctioneers of London, now one of the worlds highest ranked auctioneers, and at the other end of the spectrum, there was Bill ‘Yorkie’ Cole, the company’s ‘keeper of horse’, who revelled in the title of the company’s ‘head stable boy’, right up until his 90’s, in fact, he refused to retire, he simply ‘faded away’. He controlled our stables and dozens of horse drawn vehicles up to the 1970’s. He was a true Brighton character, whose experiences in the antique trade went way back to WW1, and, amongst other skills, he taught young Mark, as a teenager in the 1960’s, to drive a horse drawn pantechnicon with ‘Dolly’, Britain’s last surviving English dray horse that was trained for night driving in the ‘blackout’ during the blitz. See a photo of the company pantechnicon and 'Dolly' in the gallery

Mark has been a director and partner in the family businesses since 1971, specialising in elements of the family business that varied from the acquisition and export of vintage cars, mostly Rolls Royces, Bentleys, Aston Martins and Lagondas, to America, to the complete restoration and furnishing of a historical Sussex Georgian country Manor House for his late mother from the ground up, but long before that he was handling and buying swords and flintlocks since he was just seven years old, obviously in a very limited way though, naturally.

David jnr, Mark’s younger brother, also started collecting militaria when he was seven, in fact he became the youngest firearms dealer licence holder in the country, and it was he that convinced Mark that concentrating on militaria and rare books was the future for our world within the antique trade, and as you will by now guess, history, antiques, books and militaria are simply in their blood.

Thus, around 40 years ago, they decided to sell their export business and concentrate where their true hearts lie, in the world of military history and its artefacts, from antiquity to the 20th century. From fine and rare books and first editions, to antiquities and the greatest historical and beautiful samurai swords to be found. One photo in the gallery was one of the rarest books we have ever had, some years ago, a Great Gatsby Ist edition they can now command up to $360,000

One photo in the gallery is of Mark, some few years ago with his then new lockdown companion at the farm, ‘Cody’, named after Buffalo Bill naturally. Cody is now somewhat bigger! .Another photo is of two of our ten company trucks photographed just after their delivery from the signwriters. As you can see we always enjoyed a very old fashioned British tradition of having our vehicles fully liveried, hand sign written and artistically painted by our local and very talented artisans. Vehicles that ranged from our many horse drawn vehicles, to our 1930’s Bedford generator lorry that doubled up during WW2 as a mobile searchlight for the local anti-aircraft artillery installations, and then to our more modern fleet from the 1950’s to the 1980’s. The green liveried Leyland truck in the photograph was hand painted with a massive representation of the scene of the chariot race from Chuck Heston’s movie spectacular Ben Hur, and on the other side a huge copy of Lady Butler’s Charge of the Heavy Brigade. Each painting took over three months to complete. When we called Chuck in America to show him the completed livery, painted in his honour, he was delighted and very impressed and promised to visit us again to see it personally in all its glory, sadly his filming schedules for his 1970’s blockbuster disaster movies such as ‘Earthquake’ prevented it. Chuck was recommended to us years before by one of his co-stars in Solyent Green, one of Hollywood’s true greats, {alongside Chuck} Edward G. Robinson, who used to buy, undervalued {then}, impressionist paintings from David snr in the 1960’s. read more

Price

on

Request

An Absolute Beauty of a Fine, Koto Period Katana, Signed Bishu Osafune Kiyomitsu & Dated 1573 The Tsuba is Kinai School, a Sukashi Round Tsuba, of An Aoi,

A very good Koto period sword, with a beautiful polished blade. Two stage black lacquer saya with two tone counter striping at the top section and ishime stone matt lacquer at the bottom, it has an iron Higo style kojiri bottom chape inlaid with gold. The fuchigashira are shakudo copper with a nanako ground decorated with takebori carved ponies over decorated in pure gold, with bocage of a Japanese white pine tree above the pony on the kashira. The tsuba is a Kinai school sukashi round tsuba, in the form of an aoi, or hollyhock plant heightened with gold inlays, including Arabesque scrolls, and leaves. the tsuba came from likely a branch of the Miochin (Group IV), this family was founded by Ishikawa Kinai, who moved from Kyoto to Echizen province and died in 1680. The succeeding masters, however, bore the surname of Takahashi. All sign only Kinai Japanese text, with differences in the characters used and in the manner of writing them.

Futaba aoi is a Japanese term for the Asarum caulescens plant, which has two leaves and is often mistakenly called a "hollyhock" due to its use in the Aoi Matsuri festival. The distinctive heart-shaped leaves of futaba aoi are used to decorate participants and items in the Aoi Matsuri, which is a major festival in Kyoto. The plant is sacred to the Shimogamo and Kamigamo shrines and also served as the crest for the powerful Tokugawa Shogunate family.

The Kinai made guards only, of hard and well forged iron usually coated with the black magnetic oxide. They confined themselves to pierced relief showing extraordinary cleanness both of design and execution. Any considerable heightening of gold is found as a rule only in later work. Dragons in the round appear first in guards by the third master, fishes, birds, etc., in those of the fifth; while designs of autumn flowers and the like come still later. There are examples of Kinai tsuba in the Ashmolean and the British Museum. Made around to decades before but certainly used in the time of the greatest battle in samurai history "The Battle of Sekigahara" Sekigahara no Tatakai was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 that preceded the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate. Initially, Tokugawa's eastern army had 75,000 men, while Ishida's western army numbered 120,000. Tokugawa had also sneaked in a supply of arquebuses. Knowing that Tokugawa was heading towards Osaka, Ishida decided to abandon his positions and marched to Sekigahara. Even though the Western forces had tremendous tactical advantages, Tokugawa had already been in contact with many daimyo in the Western Army for months, promising them land and leniency after the battle should they switch sides.

Tokugawa's forces started the battle when Fukushima Masanori, the leader of the advance guard, charged north from Tokugawa's left flank along the Fuji River against the Western Army's right centre. The ground was still muddy from the previous day's rain, so the conflict there devolved into something more primal. Tokugawa then ordered attacks from his right and his centre against the Western Army's left in order to support Fukushima's attack.

This left the Western Army's centre unscathed, so Ishida ordered this unit under the command of Shimazu Yoshihiro to reinforce his right flank. Shimazu refused as daimyos of the day only listened to respected commanders, which Ishida was not.

Recent scholarship by Professor Yoshiji Yamasaki of Toho University has indicated that the Mori faction had reached a secret agreement with the Tokugawa two weeks earlier, pledging neutrality at the decisive battle in exchange for a guarantee of territorial preservation, and was a strategic decision on Mori Terumoto's part that later backfired.

Fukushima's attack was slowly gaining ground, but this came at the cost of exposing their flank to attack from across the Fuji River by Otani Yoshitsugu, who took advantage of this opportunity. Just past Otani's forces were those of Kobayakawa Hideaki on Mount Matsuo.

Kobayakawa was one of the daimyos that had been courted by Tokugawa. Even though he had agreed to defect to Tokugawa's side, in the actual battle he was hesitant and remained neutral. As the battle grew more intense, Tokugawa finally ordered arquebuses to fire at Kobayakawa's position on Mount Matsuo to force Kobayakawa to make his choice. At that point Kobayakawa joined the battle as a member of the Eastern Army. His forces charged Otani's position, which did not end well for Kobayakawa. Otani's forces had dry gunpowder, so they opened fire on the turncoats, making the charge of 16,000 men mostly ineffective. However, he was already engaging forces under the command of Todo Takatora, Kyogoku Takatsugu, and Oda Yuraku when Kobayakawa charged. At this point, the buffer Otani established was outnumbered. Seeing this, Western Army generals Wakisaka Yasuharu, Ogawa Suketada, Akaza Naoyasu, and Kutsuki Mototsuna switched sides. The blade is showing a very small, combat, sword to sword, thrust from a blade tip, or, possibly a deflected arrow impact, this tiny wound so to speak should never be polished away, this is known as a most honourable battle scar, and certainly no detriment to the blade, and that likely saved the owner of the swords life in a hand to hand combat situation. See close up photo 9 in the gallery, tiny impact of around 1mm with slight bruising below over a maximum total length 5mm, max impact depth around 1mm read more

8750.00 GBP

A Fine Signed Shinto O-Tanto Signed Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro.

Signed Shinto Tanto, by a master smith bearing the honorific title Assistant Lord of Yamoto.

A Samurai's personal dagger signed Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro. A Smith who had a very high ranking title A very nice signed Tanto, in full polish, with an early, Koto, Kamakuribori Style Iron Tsuba. The tsuba is probably Muromachi period around 1450, carved in low relief to one side. 6.5cm. Plain early iron Koshira. The blade in nice polish, itami grain and a medium wide sugaha hamon signed with his high ranking official title Yamoto Daijo Kanehiro [Kane Hiro, Assistant Lord of Yamoto Province] circa 1660. He lived in Saga province. Superb original Edo period ribbed lacquer saya.the saya has a usual side pocket to fit a kozuka utility knife. These knives were always a separate non matching and disconnected part of the dagger. Black silk binding over silver feather menuki. The samurai were bound by a code of honour, discipline and morality known as Bushido or ?The Way of the Warrior.? If a samurai violated this code of honour (or was captured in battle), a gruesome ritual suicide was the chosen method of punishment and atonement. The ritual suicide of a samurai or Seppuku can be either a voluntary act or a punishment, undertakan usually with his tanto or wakazashi. The ritual suicide of a samurai was generally seen as an extremely honourable way to die, after death in combat. read more

3995.00 GBP

A Most Scarce Antique Samurai Commander's Saihai, A Samurai Army Signalling Baton

Edo period. From a pair of different forms of saihai acquired by us.

For a commander to signal troop movements to his samurai army in battle. A Saihai, a most lightweight item of samurai warfare, and certainly a most innocuous looking instrument, despite being an important part of the control of samurai troop movements in combat, usually consisted of a lacquered wooden haft with metal ends. The butt had a hole for a cord for the saihai to be hung from the armour of the samurai commander when not being used. The head of the saihai had a hole with a cord attached to a tassel of strips of lacquered paper, leather, cloth or yak hair, rarest of all used metal strips. This example uses yak hair.

We show the lord Uesugi Kenshin holding his in an antique woodblock print in the gallery.

The saihai first came into use during the 1570s and the 1590s between the Genki and Tensho year periods. Large troop movements and improved and varied tactics required commanders in the rear to be able to signal their troops during a battle Uesugi Kenshin (February 18, 1530 - April 19, 1578) was a daimyo who was born as Nagao Kagetora, and after the adoption into the Uesugi clan, ruled Echigo Province in the Sengoku period of Japan. He was one of the most powerful daimyos of the Sengoku period. While chiefly remembered for his prowess on the battlefield, Kenshin is also regarded as an extremely skillful administrator who fostered the growth of local industries and trade; his rule saw a marked rise in the standard of living of Echigo.

Kenshin is famed for his honourable conduct, his military expertise, a long-standing rivalry with Takeda Shingen, his numerous campaigns to restore order in the Kanto region as the Kanto Kanrei, and his belief in the Buddhist god of war Bishamonten. In fact, many of his followers and others believed him to be the Avatar of Bishamonten, and called Kenshin "God of War". read more

650.00 GBP