Japanese

A Beautiful Shinto Katana By Kaga Kiyomitsu With NTHK Kanteisho Papers

With super original Edo period koshirae mounts and fittings. Higo fuchigashira with pure gold onlay with a war fan and kanji seal stamp. Shakudo menuki under the hilt wrap of samurai warriors fighting with swords and polearm. Iron plate o-sukashi tsuba, black lacquer saya with buffalo horn kurigata. Superb hamon and polish with just a few aged surface stains see photo 7

The Hamon is the pattern we see on the edge of the blade of any Nihonto (日本刀) and it is not merely aesthetic, but is due to the differential tempering with clay applied to weapons in the forging process. Japanese katanas are unique in the way of the forging process, where apart from the materials the system is tremendously laborious. In short, before temper, the steel has different clays applied that when submerged in water causing the characteristic blade curvature and the pattern of the hamon. This also causes the katanas to be flexible and can be very sharp, since the hardening of the steels at different temperatures causes a part of the sword to be softer and more flexible called Mune or loin and the other harder and brittle, thus having a High quality cutting edge capable of making precise and lethal cuts.

There are various types and variants, some simple and others very complex. Depending on how the clay is applied, it will form some patterns or others.

According to legend, Amakuni Yasutsuna developed the process of differential hardening of the blades around the 8th century. The emperor was returning from battle with his soldiers when Yasutsuna noticed that half of the swords were broken:

Amakuni and his son, Amakura, picked up the broken blades and examined them. They were determined to create a sword that will not break in combat and they were locked up in seclusion for 30 days. When they reappeared, they took the curved blade with them. The following spring there was another war. Again the soldiers returned, only this time all the swords were intact and the emperor smiled at Amakuni.

Although it is impossible to determine who invented the technique, surviving blades from Yasutsuna around AD 749–811 suggest that, at the very least, Yasutsuna helped establish the tradition of differentially hardening blades.

By the time Ieyasu Tokugawa unified Japan under his rule at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, only samurai were permitted to wear the sword. A samurai was recognised by his carrying the feared daisho, the big sword daito, little sword shoto of the samurai warrior. These were the battle katana, the big sword, and the wakizashi, the little sword. The name katana derives from two old Japanese written characters or symbols: kata, meaning side, and na, or edge. Thus a katana is a single-edged sword that has had few rivals in the annals of war, either in the East or the West. Because the sword was the main battle weapon of Japan's knightly man-at-arms (although spears and bows were also carried), an entire martial art grew up around learning how to use it. This was kenjutsu, the art of sword fighting, or kendo in its modern, non-warlike incarnation. The importance of studying kenjutsu and the other martial arts such as kyujutsu, the art of the bow, was so critical to the samurai, a very real matter of life or death, that Miyamoto Musashi, most renowned of all swordsmen, warned in his classic The Book of Five Rings: The science of martial arts for warriors requires construction of various weapons and understanding the properties of the weapons. A member of a warrior family who does not learn to use weapons and understand the specific advantages of each weapon would seem to be somewhat uncultivated. We rarely have swords with papers for our swords mostly came to England in the 1870's long before 'papers' were invented, and they have never returned to Japan for inspection and papers to be issued. However, on occasion we acquire swords from latter day collectors that have had swords papered in the past 30 years or so., and this is one of those. read more

7450.00 GBP

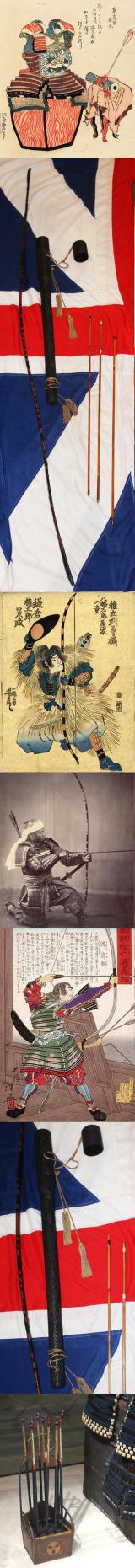

A Rare, Original, Japanese Antique Edo Period Samurai War Bow 'Daikyū ' With Urushi Lacquered Woven Rattan Quiver 'Yabira Yazutsu' With 3 'Ya' Arrows

A wonderful, original, antique Edo period {1603-1863} Samurai long war bow 'Yumi', made in either yohonhigo or gohonhigo form {4 piece or 5 piece bamboo laminate core, that is surrounded by wood and bamboo, then bound with rattan and lacquered}

Acquired by us by personally being permitted to select from the private collection one of the world's greatest, highly respected and renown archery, bow and arrow experts. Who had spent his life travelling the world to lecture on archery and to accumulate the finest arrows and bows he could find. .

Edo Era, 1600 to 1700's, with practice arrows, unfeathered, that fit into in a lacquer quiver {yabira yazutsu} with three arrows {ya}. we show a photo in the gallery from a samurai museum display that shows a practice arrow stand with the same form of flightless 'ya' inbedded in sand within the stand.

The arrows are made using yadake bamboo (Pseudosasa Japonica), a tough and narrow bamboo long considered the choice material for Japanese arrow shafts. The lidded quiver is a beautiful piece of craftsmanship in hardened urushi lacquer on woven rattan. Practice arrows were a fundamental part of samurai bowmanship.

These sets are very rarely to be seen and we consider ourselves very fortunate, indeed privileged, to offer another one.

It was from the use of the war bow or longbow in particular that Chinese historians called the Japanese 'the people of the longbow'. As early as the 4th century archery contests were being held in Japan. In the Heian period (between the 8th and 12th centuries) archery competitions on horseback were very popular and during this time training in archery was developed. Archers had to loose their arrows against static and mobile targets both on foot and on horseback. The static targets were the large kind or o-mato and was set at thirty-three bow lengths and measured about 180cm in diameter; the deer target or kusajishi consisted of a deer's silhouette and was covered in deer skin and marks indicated vital areas on the body; and finally there was the round target or marumono which was essentially a round board, stuffed and enveloped in strong animal skin. To make things more interesting for the archer these targets would be hung from poles and set in motion so that they would provide much harder targets to hit. Throughout feudal Japan indoor and outdoor archery ranges could be found in the houses of every major samurai clan. Bow and arrow and straw targets were common sights as were the beautiful cases which held the arrows and the likewise ornate stands which contained the bow. These items were prominent features in the houses of samurai. The typical longbow, or war bow (daikyu), was made from deciduous wood faced with bamboo and was reinforced with a binding of rattan to further strengthen the composite weapon together. To waterproof it the shaft was lacquered, and was bent in the shape of a double curve. The bowstring was made from a fibrous substance originating from plants (usually hemp or ramie) and was coated with wax to give a hard smooth surface and in some cases it was necessary for two people to string the bow. Bowstrings were often made by skilled specialists and came in varying qualities from hard strings to the soft and elastic bowstrings used for hunting; silk was also available but this was only used for ceremonial bows. Other types of bows existed. There was the short bow, one used for battle called the hankyu, one used for amusement called the yokyu, and one used for hunting called the suzume-yumi. There was also the maru-ki or roundwood bow, the shige-no-yumi or bow wound round with rattan, and the hoko-yumi or the Tartar-shaped bow. Every Samurai was expected to be an expert in the skill of archery, and it presented the various elements, essence and the representation of the Samurai's numerous skills, for hunting, combat, sport and amusement, and all inextricably linked together.

The mounted archer mainly controls his horse with his knees, as he needs both hands to draw and shoot his bow. As he approaches his target, he brings his bow up and draws the arrow past his ear before letting the arrow fly with a deep shout of In-Yo-In-Yo (darkness and light).

Yabusame (流鏑馬) is a type of mounted archery in traditional Japanese archery. An archer on a running horse shoots three special "turnip-headed" arrows successively at three wooden targets.

This style of archery has its origins at the beginning of the Kamakura period. Minamoto no Yoritomo became alarmed at the lack of archery skills his samurai possessed. He organized yabusame as a form of practice.

Nowadays, the best places to see yabusame performed are at the Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū in Kamakura and Shimogamo Shrine in Kyoto (during Aoi Matsuri in early May). It is also performed in Samukawa and on the beach at Zushi, as well as other locations.

On his final day in Japan in May 1922, Edward, Prince of Wales was entertained by Prince Shimazu Tadashige (1886–1968), son of the last feudal lord of the Satsuma domain. Lunch was served at Prince Shimazu’s villa, followed by an archery demonstration. Afterwards, the Prince of Wales was presented with a complete set for archery practice, including an archer’s glove, arm guard and reel for spare bowstrings read more

3550.00 GBP

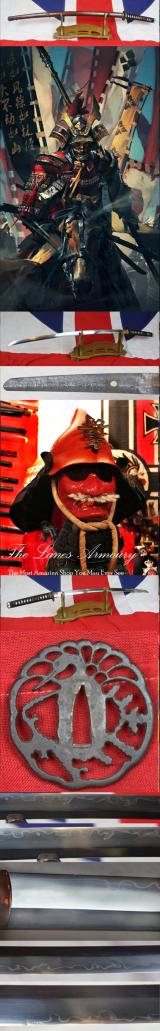

A Fine Shinto Samurai Katana Signed By Mino Swordsmith, Nodagoro Fujiwara Kanesada Circa 1720 Around 300 Years Old, With a Horai-zu Style Tsuba

He also signed Kinmichi. see Hawley’s Japanese Swordsmiths, ID KAN533 who was active in the Mino province between 1716-1736. A beautiful sword with a fabulous hamon mounted handachi style. The photos showpresent It is an original Edo period mounted handachi semi tachi form katana with iron mounts of fine quality. The original Edo saya has a beautiful rich red lacquer with flecks of pure gold.

The Edo tsuba is o-sukashi, in iron, a Horai-zu style tsuba that has a motif of crane, the symbol of long life. The crane and/or turtle and/or rocks and/or pine trees and/or bamboo are often referred to as a 蓬莱図 (Hōrai-zu) crane pattern design. The sword was being worn more and more edge up when on foot, but edge down on horseback as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need to be worn in either style. The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or daimyo, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could read and they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry. Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu to stop the spear exanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai).

Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesized in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality.The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they could be trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony. The blade shows a super hamon, and polish with a couple of very small edge pits near the habaki on just one side. read more

8750.00 GBP

A Stunning Edo Period Tettsu {iron Plate} Krishitan {Christian.} Tsuba, Of The Holy Cross, Heavenly Eight Pointed Stars in Gold, & The River Of Life in Silver. In Superb Condition & From A Very Fine Collection of Tsuba.

A stunning Krishitam sukashi piercing of the cross with a silver river and gold eight pointed star inlays. With a kozuka hitsu-ana, and kogai hitsu ana

The Bible starts with an account of a river watering the Garden of Eden. It flowed from the garden separating out into four headwaters. The rivers are named, flowing into different areas of the world,

Eight pointed stars symbolise the number of regeneration and of Baptism. The Stars and The River as Christian Symbols, are images or symbolic representation with sacred significance. The meanings, origins and ancient traditions surrounding Christian symbols date back to early times when the majority of ordinary people were not able to read or write and printing was unknown. Many were 'borrowed' or drawn from early pre-Christian traditions.

The Hidden Christians quieted their public expressions and practices of faith in the hope of survival from the great purge. They also suffered unspeakably if captured and failed to renounce their Christian beliefs.

In Silence, Endo depicts the trauma of Rodrigues’ journey into Japan through his early encounter with an abandoned and destroyed Christian village. Rodrigues expresses his distress over the suffering of Japanese Christians and he reports the “deadly silence.”

‘I will not say it was a scene of empty desolation. Rather was it as though a battle had recently devastated the whole district. Strewn all over the roads were broken plates and cups, while the doors were broken down so that all the houses lay open . . . The only thing that kept repeating itself quietly in my mind was: Why this? Why? I walked the village from corner to corner in the deadly silence.

...Somewhere or other there must be Christians secretly living their life of faith as these people had been doing . . . I would look for them and find out what had happened here; and after that I would determine what ought to be done.”

- Silence, Shusaku Endo

Two images in the gallery are drawings of bronze fumi-e in use during the 1660s in Japan, during the time of the persecution. Each of these drawings mirrors actual brass fumi-e portraying Stations of the Cross, which are held in the collections of the Tokyo National Museum

The current FX series 'Shogun' by Robert Clavell is based on the true story of William Adams and the Shogun Tokugawa Ieyesu, and apart from being one of the very best film series yet made, it shows superbly and relatively accurately the machinations of the Catholic Jesuits to manipulate the Japanese Regents and their Christian convert samurai Lords.

Oda Nobunaga (1534–82) had taken his first step toward uniting Japan as the first missionaries landed, and as his power increased he encouraged the growing Kirishitan movement as a means of subverting the great political strength of Buddhism. Oppressed peasants welcomed the gospel of salvation, but merchants and trade-conscious daimyos saw Christianity as an important link with valuable European trade. Oda’s successor, Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537–98), was much cooler toward the alien religion. The Japanese were becoming aware of competition between the Jesuits and the Franciscans and between Spanish and Portuguese trading interests. Toyotomi questioned the reliability of subjects with some allegiance to the foreign power at the Vatican. In 1587 he ordered all foreign missionaries to leave Japan but did not enforce the edict harshly until a decade later, when nine missionaries and 17 native Kirishitan were martyred.

After Toyotomi’s death and the brief regency of his adopted child, the pressures relaxed. However, Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the great Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1867), gradually came to see the foreign missionaries as a threat to political stability. By 1614, through his son and successor, Tokugawa Hidetada, he banned Kirishitan and ordered the missionaries expelled. Severe persecution continued for a generation under his son and grandson. Kirishitan were required to renounce their faith on pain of exile or torture. Every family was required to belong to a Buddhist temple, and periodic reports on them were expected from the temple priests.

By 1650 all known Kirishitan had been exiled or executed. Undetected survivors were driven underground into a secret movement that came to be known as Kakure Kirishitan (“Hidden Christians”), existing mainly in western Kyushu island around Nagasaki and Shimabara. To avoid detection they were obliged to practice deceptions such as using images of the Virgin Mary disguised as the popular and merciful Bōsatsu (bodhisattva) Kannon, whose gender is ambiguous and whom carvers often render as female.

The populace at large remained unaware that the Kakure Kirishitan managed to survive for two centuries, and when the prohibition against Roman Catholics began to ease again in the mid-19th century, arriving European priests were told there were no Japanese Christians left. A Roman Catholic church set up in Nagasaki in 1865 was dedicated to the 26 martyrs of 1597, and within the year 20,000 Kakure Kirishitan dropped their disguise and openly professed their Christian faith. They faced some repression during the waning years of the Tokugawa shogunate, but early in the reforms of the emperor Meiji (reigned 1867–1912) the Kirishitan won the right to declare their faith and worship publicly.

Some wear to the gold and silver inlays on the reverse side. read more

1495.00 GBP

A Beautiful, Edo Period, 18th century Hanbo, A Samurai Warrior's Face Armour Mask

Black lacquer decor throughout, with vermillion lacquer interior. The expression is fierce/noble with protruding chin, the shape is elegant and very well refined. three lame yodarekake, with hooked standing cord pegs. Face armour, of this type is called hanbo.

They were worn with the Samurai's armours to serve as a protection for the head and the face from sword cuts. There are 4 types of face armour mask designs that came into general use in Japan: happuri (which covers the forehead and cheeks), hanbō (covers the lower face, from below the nose all the way to the chin), sōmen (covers the entire face) and the me-no-shita-men (covers the face from nose to chin). We can also classify those mask depending on their facial expressions, most of which derive from the theatre masks. It has an asenagashino ana a hole under the chin to drain off perspiration and orikugi two projecting studs above the chin to provide a secure fastening to the wearer. In the 16th century Japan began trading with Europe during what would become known as the Nanban trade. Samurai acquired European armour including the cuirass and comb morion which they modified and combined with domestic armour as it provided better protection from the newly introduced matchlock muskets known as Tanegashima. The introduction of the tanegashima by the Portuguese in 1543 changed the nature of warfare in Japan causing the Japanese armour makers to change the design of their armours from the centuries old lamellar armours to plate armour constructed from iron and steel plates which was called tosei gusoku (new armours). Bullet resistant armours were developed called tameshi gusoku or (bullet tested) allowing samurai to continue wearing their armour despite the use of firearms.

The era of warfare called the Sengoku period ended around 1600, Japan was united and entered a relatively peaceful Edo period. However, the Shoguns of the Tokugawa period were most adept at encouraging clan rivalries and conflicts and battles were engaged throughout the empire. This of course suited the Shogun very well, while all his subordinate daimyo fought each other they were unlikely to conspire against him. Samurai use continued to use both plate and lamellar armour as a symbol of their status but traditional armours were no longer necessary for war, but still for battle. The face armour was not designed to have any nose protection fitted, the lacquer is original Edo period throughout with vermilion red lacquer in the interior face portion, the exterior lacquer has a fair amount of age flaking over around 6-8% of the neck defence lames. read more

1125.00 GBP

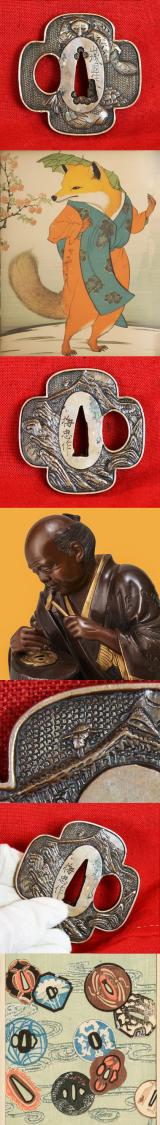

A Fine Edo Tsuba Kaga Kyoto Praying Mantis, Cricket Butterfly in Gold Inlay. From WW2 British RAF Commander & Hero Air Marshal Dowding's Collection

Circa 1730 from the family of Air Marshal Lord Dowding, commander of the Royal Airforce in WW2.

Iron plate inlaid with silver and gold superior Kaga Kyoto school tsuba of fine quality. After Hanabusa Itchō, a very popular subject in Japanese art in the late 17th to 18th century.

Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other.

2.5 inches x 2.25 inches read more

975.00 GBP

Ko Tosho School Swordsmith Made Koto Katana Tsuba Circa 1400

The strong, softly lustrous metal and very well cut, the large Hitsu-ana, and the antique chisel marks around the Hitsu-ana are all characteristic indications of early-Muromachi period works. Carved openwork clan mon. The Hitsu-ana, made when the guard was first produced, suggests that it is a work of the time of Yoshimitsu. A well worked and hammered plate. According to tradition, it says each time a Tosho made a to-ken, he made a habaki with his own hands, and at the same time he also added a single tsuba such as this.

The earliest Tosho tsuba are referred to in Japanese as Ko-Tosho old sword smith and date from the Genpei War (1180-1185) to middle Muromachi Period (1400-1500).

During the late Kamakura Period large Ko-Tosho tsuba were developed and were used mostly as field mounts for odachi by high-ranking Samurai during and after the Mongol invasion of Japan in Genko Jidai (1274-1281 ) in the Muromachi Period (1336-1573) the Ko-Tosho tsuba became even more common with the development and popularization of the onehanded sword uchigatana as the only sword of Ashigaru.

The most common design characteristic, next to the plain flat plate, for Ko-Tosho tsuba is kosukashi the simplistic use of small negative silhouetted openwork. The most common openwork designs are of mon (family crest), sun, moon, tools, plants, Buddhist, Shinto and sometimes Christian religious symbols. The plates iron is characteristically of a good temper, having good hardness and elasticity. The plate is made of local iron forged by the swordsmith or apprentice, the same as for Japanese sword blades. 74mm read more

750.00 GBP

An Iron Plate Katana Edo Tsuba Decorated With Small Figures In Rain Garb

Circa 1650. Small fishermen towing nets wearing rain hats and tied straw body coverings. With large fauna as a side decoration. With kozuka and kogaiana. The Tsuba can be solid, semi pierced of fully pierced, with an overall perforated design, but it always a central opening which narrows at its peak for the blade to fit within. It often can have openings for the kozuka and kogai to pass through, and these openings can also often be filled with metal to seal them closed. For the Samurai, it also functioned as an article of distinction, as his sole personal ornament read more

395.00 GBP

A Most Unusual & Rare Edo Period Katana Tsuba, With Rotational Fitting. This is An Incdibly Rare Form of Tsuba in that it Has Two Methods To Mount It On Katana. Vertical or Horizontal

An iron sukashi tsuba, cut with four different shaped symbols as kozuka-ana and kogai-ana, and two, North and South, or East and West facing blade apertures, to enable the rotation of the tsuba when mounting it onto the blade. Thus altering the profile of the tsuka from wide to narrow.

The tsuba is always usually a round, ovoid or occasionally squarish guard at the end of the tsuka of bladed Japanese weapons but always usually designed to be worn one way upon the sword, either the katana and its various declinations, tachi, wakizashi, tanto, and polearms that have a tsuba, such as naginata etc.

They contribute to the balance of the weapon and to the protection of the hand. The tsuba was mostly meant to be used to prevent the hand from sliding onto the blade during thrusts as opposed to protecting from an opponent's blade. The chudan no kamae guard is determined by the tsuba and the curvature of the blade. The diameter of the average katana tsuba is 7.58 centimetres (3.0-3.1 in), wakizashi tsuba is (2.4-2.6 in), and tanto tsuba is 4.5-6 cm (1.8-2.4 in).

During the Muromachi period (1333-1573) and the Momoyama period (1573-1603) Tsuba were more for functionality than for decoration, being made of stronger metals and designs. During the Edo period (1603-1868) tsuba became more ornamental and made of less practical metals such as gold.

Tsuba are usually finely decorated, and are highly desirable collectors' items in their own right. Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other. read more

585.00 GBP

A Superb Edo Period Umetada Tsuba Signed Yamashiro kuni ju Umetada Shigenari, From the Umetada Line Of Tsuba Makers of Yamashiro. Of A Carved Takebori Kitsune {Fox} Going To The Kitsune no Yomeiri {The Foxe's Wedding}

Yamashiro kuni ju Umetada shigenari, from the Umetada family residing in the province of Yamashiro, active around 1650-1700.

With a most rare feature of the punch in order to create a narrowing of the nakago-ana, bears numerous strikes of a clan mon of six plum blossom petals. At the area around the nakago-ana note there are tagane-ato (punch marks around the nakago-ana) in the form of mon

The Umetada school was one of the pivotal centres of sword-related arts between the late Momoyama period and the early Edo era. Founded in Kyōto, it stood out for its versatility and outstanding quality, covering all fields associated with the katana: restorations, horimono, suriage, kinzogan-mei, crafting of habaki, and mountings — most of these works commissioned through collaboration with the Hon’ami family, who retained exclusive rights for polishing and appraisal services.

The Umetada school was a renowned family of tsuba (sword guard) makers in Kyoto, founded in the late 16th century by Umetada Myōju. The school is known for its innovative combination of chiseling and inlay work, creating tsuba with a wide variety of styles, including intricate designs, soft metal inlays, and even European-influenced motifs. Key members of the school included Umetada Myōju, Umetada Mitsutada, Myōshin, and Jusai.

Key features of the Umetada school

Innovative techniques: The school combined traditional chiseling and inlay (zogan) techniques with unique designs.

Versatile subject matter: Tsuba often featured natural motifs like snow crystals and leaves

Use of soft metals: They were known for using soft metals like copper and brass, often with inlays of gold, silver, or shakudo.

One the principle side is the fox dressed in formal garb with a hat with his iconic big fluffy tail, and at his feet is a bound bag of precious gifts. On the opposing side is a mountain scene with the small fox figure, carrying the bag of precious gifts on a pole, wearing a jingasa hat, walking the mountain path.

The Foxes' Wedding

is less a single continuous narrative and more a widespread folk belief used to explain a specific natural phenomenon: a sunshower, where rain falls while the sun is shining. People in rural Japan once believed this meant a kitsune wedding was taking place just beyond human sight.

On a day when the sun and rain appear together, an invisible (or nearly invisible) procession of foxes can be seen or heard moving through the fields or mountains.

The foxes in the procession, having used their magical abilities to take on human form, wear traditional Japanese wedding attire. The bride wears a white kimono (a bridal kimono) and a traditional headdress, while the groom may be in formal black attire. Other fox guests wear splendid kimonos with their family crests.

The groom in traditional formal wear would wear a traditional formal hat (like an eboshi or kanmuri), fitting the description of a "fox wearing a kimono and hat" in human form for the ceremony.

The procession is often lit by kitsunebi (fox-fire), ethereal fireballs breathed out by the foxes to light their way through the night.

Human Encounters: Humans who accidentally witnessed this rare event were traditionally warned to stay indoors to avoid disruption, which could bring bad luck. Sometimes, a human might stumble upon the wedding and either be granted good fortune or become bewitched if they spoke of it.

This belief is a popular motif in traditional Japanese art (ukiyo-e prints) and theatre, such as Kabuki, where actors would wear fox masks and elaborate costumes to portray the characters. read more

995.00 GBP