A Superb Antique, Shinto Era, Unokubi (鵜首) Zukuri Blade Tantō, Late 16th To Early 17th Century, from the Battle of Sekigahara, Shinjitai: 関ヶ原の戦い; Kyūjitai: 關ヶ原の戰い With, Signed Kaboku, 'Nakago Form' Kozuka Side Knife With Imperial Chrysanthemum Mon

The kozuka {side knife} is signed, Koboku, who was a master swordsmith and surgeon to the lord of Mito. He was a famous swordsmith of legend mysteriously assassinated in 1703 during his retirement, yet not before he killed his unknown assassin using his dismembered arm.

A really nice and rare form of samurai tanto fitted with all its original Edo period koshirae Including a superb stunning urushi lacquer 'pine needle' decor saya with buffalo horn fittings, {kurigata, sayajiri}. Iron tetsu tsuba, signed, and decorated with a dragon in the foreground with mountains under clouds at the rear. Patinated copper fuchi of flowers, and a pair of iron rectagular menuki inlaid with flowers, underneath the rich brown coloured silk tsukaito {binding}. The silver inlay in the menuki is now blacked with age and very difficult to see. Made from around the era of the Battle of Sekigahara, Shinjitai: 関ヶ原の戦い; Kyūjitai: 關ヶ原の戰い

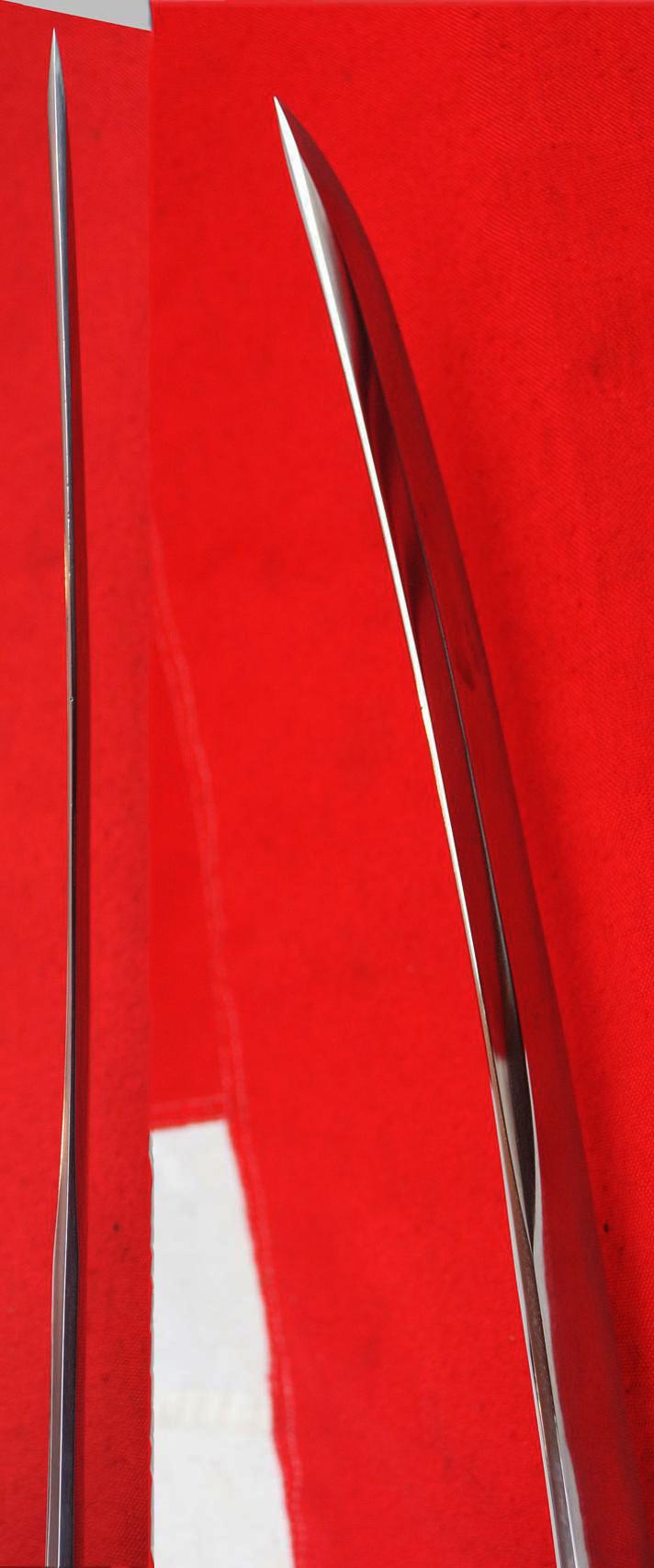

Unokubi (鵜首): Is an uncommon tantō blade style akin to the kanmuri-otoshi, with a back that grows abruptly thinner around the middle of the blade; however, the unokubi zukuri regains its thickness just before the point. There is normally a short, wide groove {hi} extending to the midway point on the blade, this is a most unusual form of unokubi zukuri blade tanto without a hi. It has a beautiful habaki, set in its original Edo period pine needle uriushi lacquered saya.The blade is absolutely beautiful.

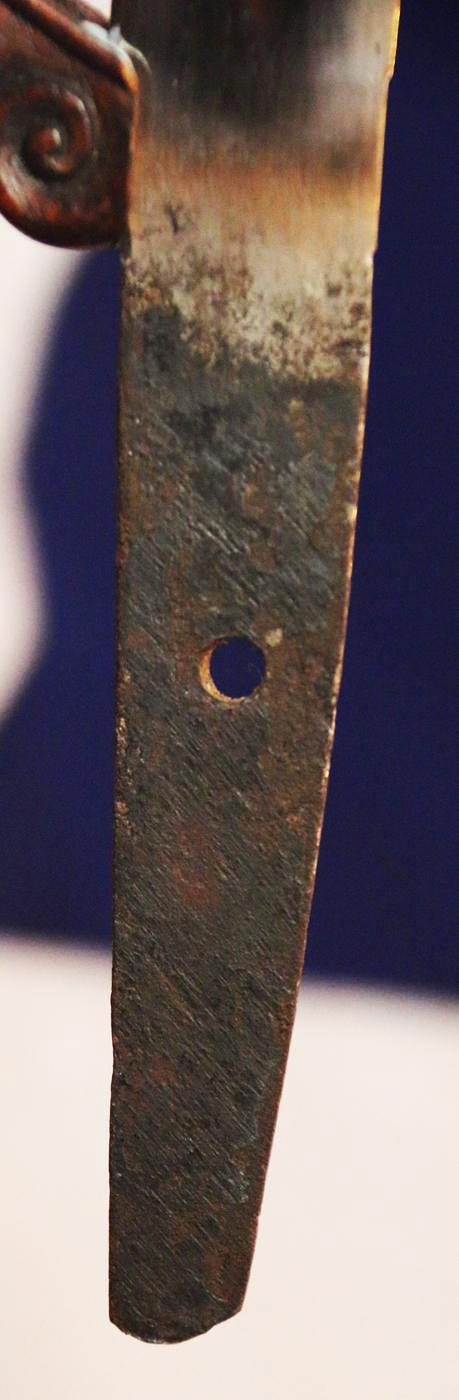

A Very Nice Edo Period Shinto Era 'Nakago Form' Kodzuka Iron body inlaid with copper , with the signature kanji of Kaboku, and the Imperial chrysanthemum mon. Kodzuka have been collectable items for many centuries, simply as works of art, even though they were functional knife handles, for the utility blades that fitted into wakizashi, tanto and katana saya. They can vary in quality, and this is a most fine example, inlaid with pure copper. What is particularly scarce is that it is shaped like the tang of the sword, complete with simulated mekugi ana, and signed in much the same way. This type is rare and very collectable. a long thin blade that slotted into it's opening, and the blade was often considered to be almost of a disposable nature, with the handle itself being the prized part.

The Battle of Sekigahara (Shinjitai: 関ヶ原の戦い; Kyūjitai: 關ヶ原の戰い,Sekigahara no Tatakai) was a decisive battle on October 21, 1600 (Keichō 5, 15th day of the 9th month) in what is now Gifu Prefecture, Japan, at the end of the Sengoku period. This battle was fought by the forces of Tokugawa Ieyasu against a coalition of Toyotomi loyalist clans under Ishida Mitsunari, several of which defected before or during the battle, leading to a Tokugawa victory. The Battle of Sekigahara was the largest battle of Japanese feudal history and is often regarded as the most important. Mitsunari's defeat led to the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate.

Tokugawa Ieyasu took three more years to consolidate his position of power over the Toyotomi clan and the various daimyō, but the Battle of Sekigahara is widely considered to be the unofficial beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, which ruled Japan for another two and a half centuries

A tanto would most often be worn by Samurai, and it was very uncommon to come across a non samurai with a tanto. It was not only men who carried these daggers, women would on occasions carry a small tanto called a kaiken in their obi which would be used for self-defence. In feudal Japan a tanto would occasionally be worn by Samurai in place of the wakizashi in a combination called the daisho, which roughly translates as big-little, in reference to the big Samurai Sword (Katana) and the small dagger (tanto). Before the rise of the katana it was more common for a Samurai to carry a tachi and tanto combination as opposed to a katana and wakizashi.

The lacquer saya has 'pine needle' decor, a highly complex design of pine needles laid upon black lacquer, in a seemingly random pattern, but in reality each pine needle was strategically placed upon them, one at a time, to give the impression they fell naturally upon the ground, from above, from a pine tree. The surface was then lacquered in clear transparent urushi lacquer to create a uniform smooth surface. in the Edo period it would take anything around a year or more to create a samurai sword saya, as the lacquer coating would be anything up to 12 coats deep, and each would take a month to dry as they were made using on natural materials, not modern quick drying synthetic cellulose lacquers as used today.

Japanese lacquer, or urushi, is a transformative and highly prized material that has been refined for well over 7000 years. The use of natural lacquer, known as urushi, has a 9,000-year history in Japan. Lacquered artifacts dating back to the prehistoric Jomon period (10,000–300 BCE) have been found at various archeological sites throughout Japan.

Cherished for its infinite versatility, urushi is a distinctive art form that has spread across all facets of Japanese culture from the tea ceremony to the saya scabbards of samurai swords

Japanese artists created their own style and perfected the art of decorated lacquerware during the 8th century. Japanese lacquer skills reached its peak as early as the twelfth century, at the end of the Heian period (794-1185). This skill was passed on from father to son and from master to apprentice.

Some provinces of Japan were famous for their contribution to this art: the province of Edo (later Tokyo), for example, produced the most beautiful lacquered pieces from the 17th to the 18th centuries. Lords and shoguns privately employed lacquerers to produce ceremonial and decorative objects for their homes and palaces.

The varnish used in Japanese lacquer is made from the sap of the urushi tree, also known as the lacquer tree or the Japanese varnish tree (Rhus vernacifera), which mainly grows in Japan and China, as well as Southeast Asia. Japanese lacquer, 漆 urushi, is made from the sap of the lacquer tree. The tree must be tapped carefully, as in its raw form the liquid is poisonous to the touch, and even breathing in the fumes can be dangerous. But people in Japan have been working with this material for many millennia, so there has been time to refine the technique!

The kozuka is signed Koboku, he was a master swordsmith and surgeon to his lord of Mito, and an extraordinarily eccentric character. He studied medicine under Tsunoda Kyuho, and he seems to have started forging swords at an early age. According to legend because he had taken up the study of western medicine and he was not satisfied with the scalpels that were available, so endeavoured to make his own. He left the employ of the Mito family in January of 1699, Genroku 12. Some say because he did not get along with his immediate superior the Karo, Nakayama Bizen no Kami, others that his peculiar behavior and egotistical manner was offending too many people and this reached the ears of the lord. House records from 1698, record that his health was failing and it was decided that he be “retired” to Mito. Perhaps he did not wish to leave Edo and be confined to Mito. Whatever the reason the house record notes that he officially asked to resign and left to devote himself to his religious studies on that date.

Five years later found him in the far north living in Oshu Nihonmatsu where one night he stood naked in his garden where he was confronted by an assassin. To this day no one knows who the man was nor why he might have been sent to kill Kaboku but his intent was clear enough. Without hesitation Kaboku, who held a mokuroku in Shibukawa-ryu Jujutsu, charged as his attacker charged him. He grabbed his left wrist with his right hand and used his own left arm to block the cut that was descending toward his head. Still clutching his severed left hand in his right he closed with his attacker and thrust the jagged bone into the mans mouth, here he fell upon him and smothered him with the bloody relic.

Kaboku then went back into his home, perhaps something the assassin had said struck him, perhaps he understood from his own wounds that he would not survive, it is not clear why but using only the right hand he drew out a tanto and took his own life. A strange end for one of the sword worlds strangest characters.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery

Code: 25707

3950.00 GBP