Antique Arms & Militaria

Archaic Chinese Warrior's Bronze Sword, Around 2500 Years Old, From the Zhou Dynasty to the Qin Dynasty, Including the Period of the Great Military Doctrine 'The Art of War' by General Sun-Tzu

Chinese Bronze 'Two Ring' Jian sword, however both the grip rings are now lacking, as is the pommel. Used in the era of the Seven Kingdoms period, likely in the Kingdom of Wu, up to the latter part of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (475 – 221 BC).

From our wonderful collection of ancient Chinese weaponry we recently acquired, another stunning ancient sword around 2500 years old or more. From the Zhou dynasty, and the area of the King's of Wu, in Chu. as this sword bears old damage it is priced accordingly, yet it is still an ancient piece of great beauty and interest.

Swords of this type are called “two-ring” swords because of the prominent rings formerly located on the hilt. This is the very type of sword used by the warriors serving under the world renowned General Sun Tzu, in the Kingdom of Wu, who is thought by many to be the finest general, philosopher and military tactician who ever lived. His 2500 year old book on the methods of warfare, tactics and psychology are still taught and highly revered in practically every officer training college throughout the world.

We show a painting in the gallery of a chariot charge by a Zhou dynasty warrior armed with this very form of sword.

The Chinese term for this form of weapon is “Jian” which refers to a double-edged sword. This style of Jian is generally attributed to either the Wu or the Yue state. The sword has straight graduated edges reducing to a pointed tip, which may indicate an earlier period Jian.

The blade is heavy with a midrib and tapered edges

A very impressive original ancient Chinese sword with a long, straight blade with a raised, linear ridge down its centre. It has a very shallow, short guard. The thin handle would have had leather or some other organic material such as leather or hemp cord, wrapped around it to form a grip. At the top once had a round, likely dished pommel

The Seven Kingdom or Warring States period in Chinese history was one of instability and conflict between many smaller Kingdom-states. The period officially ended when China was unified under the first Emperor of China, Qin pronounced Chin Shi Huang Di in 221 BC. It is from him that China gained its name.

The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was among the most culturally significant of the early Chinese dynasties and the longest lasting of any in China's history, divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771-256 BCE). It followed the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE), and preceded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE, pronounced “chin”) which gave China its name.

In the early years of the Spring and Autumn Period, (770-476 BC) chivalry in battle was still observed and all seven states used the same tactics resulting in a series of stalemates since, whenever one engaged with another in battle, neither could gain an advantage. In time, this repetition of seemingly endless, and completely futile, warfare became simply the way of life for the people of China during the era now referred to as the Warring States Period. The famous work The Art of War by Sun-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) was written during this time, recording precepts and tactics one could use to gain advantage over an opponent, win the war, and establish peace.

Sun Tzu was a Chinese general, military strategist, writer, and philosopher who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of The Art of War, an influential work of military strategy that has affected both Western and East Asian philosophy and military thinking. His works focus much more on alternatives to battle, such as stratagem, delay, the use of spies and alternatives to war itself, the making and keeping of alliances, the uses of deceit, and a willingness to submit, at least temporarily, to more powerful foes. Sun Tzu is revered in Chinese and East Asian culture as a legendary historical and military figure. His birth name was Sun Wu and he was known outside of his family by his courtesy name Changqing The name Sun Tzu by which he is more popularly known is an honorific which means "Master Sun".

Sun Tzu's historicity is uncertain. The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian and other traditional Chinese historians placed him as a minister to King Helü of Wu and dated his lifetime to 544–496 BC. Modern scholars accepting his historicity place the extant text of The Art of War in the later Warring States period based on its style of composition and its descriptions of warfare. Traditional accounts state that the general's descendant Sun Bin wrote a treatise on military tactics, also titled The Art of War. Since Sun Wu and Sun Bin were referred to as Sun Tzu in classical Chinese texts, some historians believed them identical, prior to the rediscovery of Sun Bin's treatise in 1972.

Sun Tzu's work has been praised and employed in East Asian warfare since its composition. During the twentieth century, The Art of War grew in popularity and saw practical use in Western society as well. It continues to influence many competitive endeavours in the world, including culture, politics, business and sports.

The ancient Chinese people worshipped the bronze and iron swords, where they reached a point of magic and myth, regarding the swords as “ancient holy items”. Because they were easy to carry, elegant to wear and quick to use, bronze swords were considered a status symbol and an honour for kings, emperors, scholars, chivalrous experts, merchants, as well as common people during ancient dynasties. For example, Confucius claimed himself to be a knight, not a scholar, and carried a sword when he went out. The most famous ancient bronze sword is called the “Sword of Gou Jian”.

This is one of a stunning collection of original archaic bronze age weaponry we have just acquired and has now arrived. Many are near identical to other similar examples held in the Metropolitan in New York, the British royal collection, and such as the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, China.

As with all our items, every piece is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity read more

1495.00 GBP

A Stunning 1796 Scottish Flank Officer's Combat Sword, Napoleonic Wars, Peninsular & Waterloo Period. For Coldstream Guards, With One Of The Most Beautiful, Finest Quality & Unique Blade Engravings We Have Ever Seen. By Hunter of Edinburgh

Very likely a Coldstream Regiment of Foot Guards, flank company officer's sword for use in the Coldstreamers grenadier 'flank company' of the regiment. Almost certainly used by a Coldstream flank company officer in the Peninsular War and Waterloo, and even at Hougemont itself, for that, for us, there is little doubt. Each battalion of the British army included a light infantry company and a grenadier company; they were known as "flank companies" and were made up of the best soldiers in the battalion. During field operations they normally were pooled to form special corps of light infantry and grenadiers. This wondrous sword has a fully deluxe engraved blade, engraved and etched with royal crown, royal crest and cypher, a seated Brittania and an Angel blowing the trumpet of Victory, stands of arms, thistles and roses, with fine contra blueing, and fully intact to one blade face. Although fully engraved and etched on both sides, the obverse side is more worn, and has the blueing to that side worn away entirely. Possibly due to it being on display, hanging against a wall of a stately home or castle, for a century and a half or more. Custom made for its owner by Hunter of Edinburgh, and it was Hunter that was the dominant and near exclusive supplier of swords to all Coldstream guards regimental officers from before, and during, the Napoleonic wars. Also, the finest quality deluxe and extravagant nature of this blade is a typical example of the elaborate display of an elite Guards officer's status. The sword maker/retailer's name, Hunter, and his location, Edinburgh, is etched upon the obverse side of the blade, but very worn see photo 8 . In at least two seminal works of sword makers both Sword for Sea Service, and Swords and Sword Makers of England and Scotland it is clearly recorded that 'Hunter of Edinburgh' specifically supplied the officers of the Coldstream Guards from 1780 to at least 1810. The elite Coldstream Regiment saw extensive service in the wars against the French Revolution and in the Napoleonic Wars. Under the command of Sir Ralph Abercrombie, it defeated French troops in Egypt. In 1807, it took part in the investment of Copenhagen. In January 1809, it sailed to Portugal to join the forces under Sir Arthur Wellesley. In 1814, it took part in the Battle of Bayonne, in France, where a cemetery keeps their memory. The 2nd Battalion joined the Walcheren Expedition. Later, it served as part of the 2nd Guards Brigade in the chateau of Hougoumont on the outskirts of the Battle of Waterloo. This defence is considered one of the greatest achievements of the regiment, and an annual ceremony of "Hanging the Brick" is performed each year in the Sergeants' Mess to commemorate the efforts of Cpl James Graham and Lt-Col James MacDonnell, who shut the North Gate after a French attack. The Duke of Wellington himself declared after the battle that "the success of the battle turned upon closing the gates at Hougoumont". The night before the battle of Waterloo, Wellington sent MacDonnell with the guards to occupy the Chateau de Hougoumont. MacDonnell held this key position against overwhelming French attacks during the early part of the battle. When French troops were forcing their way into the courtyard, MacDonnell, aided by a sergeant, closed and held the gates by sheer physical strength. Chosen by Wellington for the award of £1,000 as the ‘bravest man in the British Army,’ MacDonnell insisted upon sharing the sum with his sergeant.

A painting by Dighton of the Coldstream Guards coming to the aid of the defenders. They fought their way into the chateau. Lieut-Col Daniel Mackinnon of the Grenadier Company has his back to us on the right. He was wounded in the knee but carried on until he became weak through loss of blood. He survived the battle and became commanding officer of the regiment in 1830.

Map of Hougoumont

From Wellington's viewpoint the three main buildings that formed landmarks on the battlefield were La Haye Sainte in the middle, Papelotte on the left, and Hougoumont on the right. The chateau of Hougoumont was a manor house and farm with ornamental garden, orchard and woods. The 1st Guards were posted on the ridge behind the chateau and some of them had been involved in a skirmish around Hougoumont on the evening of the 17th. But the defence of the buildings was given, initially, to the Light Companies of the Coldstream and Scots Guards under the command of Coldstreamer, Lieut-Col James Macdonnell, the personal choice of Wellington. They spent the morning barricading all the gateways into the enclosure of buildings, except for the north gate which had to remain accessible to supplies and reinforcements.

The first attack came from troops in Reille's Corps under the command of Jerome, who was ordered by his brother Napoleon, to take Hougoumont at all costs. He took the order literally and many Frenchmen died in the attempt, by the end of the day the number was 8,000. The first attack was repulsed by firing from within the chateau and outside. More attacks came, but thankfully without artillery which could have destroyed the walls of the enclosure. Those guardsmen who were still outside managed to withdraw into the chateau and the north gate was shut, but before it could be barricaded it was rushed by a party of 12 brave Frenchmen led by Lieutenant Legros, a large man with an axe. They barged in but all died fighting. Only a young French drummer was allowed to live. The closing and barricading of the gates was accomplished by Macdonnell and nine others.

Fighting Outside Hougoumont

Sir John Byng ordered three companies of the Coldstream Guards under Lt-Col Dan Mackinnon to go down and support the beleaguered garrison. They drove the French from the west wall and entered the enclosure. Napoleon himself became involved and ordered howitzer fire to be used. Incendiary shells were fired at the buildings and they caught fire, killing many of the wounded who were inside. Colonel Alexander Woodford entered the struggle with the remainder of the Coldstream Guards, leaving two companies on the ridge to guard the Colours. They fought their way into Hougoumont to reinforce the defenders. Woodford outranked Macdonnell but at first declined to take command away from him.

The End of the Battle

The situation became critical at one stage so that the King's German Legion were sent forward to counter-attack on the outside of the building. This effectively proved the last straw for the French who gave up their attempts to take Hougoumont. Woodford was commanding the garrison at the end of the battle when Wellington ordered a general advance to pursue the French. The force inside the enclosure ranged from 500 to 2000, but they managed to keep a whole French Corps occupied all day. The casualty figures for the Coldstream Guards on the 18th June was one officer and 54 other ranks killed, 7 officers and 249 other ranks wounded. Four men were unaccounted for. No scabbard read more

2750.00 GBP

A Superb, Original, 1879 Zulu War Small Cow-Hide Zulu Shield. Likely A Zulu Iwahu Shield. From the Time Of Islandwana, Rorke's Drift and Ulundi. Souvenir of the Zulu War

The ideal size for a historical display today, of a private collector or museum, such as combined with original Zulu War pieces, such as spears & knopkerrie {war clubs}.

Small cow-hide shields such as this were developed into larger versions, known as Isihlangu, in the early 19th century by Shaka kaSenzangakhona, a great warrior king and innovator who transformed Zulu warriors into a potent military machine. Shaka also introduced a new short, stabbing spear and a new style of fighting whereby the Zulu could barge his enemy off balance with the shield, or use it to hook around hid enemy's shield, pull it across his body and stab him under the left arm. These new weapons and methods, combined with tactical brilliance on the battlefield allowed the Zulu to conquer their neighbours, consolidate economic and military power, and resist European invasion for a long period.

The Zulu military system was based on the close bonding of unmarried men grouped by age. Brought together in a barracks at about 18-20 years old, a group of 350-400 men developed a strong identity as a 'regiment' or impi thanks to insignia such as the patterning on their shields. Each impi had its own kraal of cattle, and King Shaka assigned each a specific hide patterning. Impi kept their shields turned face-inwards under their arms while charging the enemy, until the last moment when the entire regiment turned their shields to face the enemy - who would only realise which of Shaka's regiments they faced with seconds to spare. This idea that the shield represented one's military identity is enshrined in the Zulu expression, "to be under somebody's shield", meaning to be under their protection.

Yet the different colours and markings on shields did more than just identify a specific impi. Great warriors had white shields with one or two spots, the young and inexperienced had black shields whilst the middle warriors had red shields. This demarcation formed the basis of the Zulu's famous battle formation imitating the horns, chest and loins of a cow, which is thought to have originated in hunting as a means of encircling game. During combat, the youngest and swiftest warriors, carrying dark shields, made up the 'horns', attempting to surround the enemy and draw him into the 'chest', whereupon the elite white shields would destroy him.

After a year of basic training, young warriors were sent home to tend their family cattle herds, mobilising for active service for four months of each year thereafter. Impi were disbanded when the men reached their late thirties and, under Shaka, it was only then they could marry. However, by the time of Zulu War of 1879, in the reign of Cetewayo, the marriage age was much younger and married warriors were no longer regarded as inferior and could bear a white shield in battle. Whether a Zulu warrior was active or retired, his shield remained an important symbol of his status upon entering marriage.

The Zulus, 22,000 strong, attacked the camp at Isandlwana and their sheer numbers overwhelmed the British. As the officers paced their men far too far apart to face the coming onslaught. During the battle Lieutenant-Colonel Pulleine ordered Lieutenants Coghill and Melvill to save the Queen's Colour—the Regimental Colour was located at Helpmakaar with G Company. The two Lieutenants attempted to escape by crossing the Buffalo River where the Colour fell and was lost downstream, later being recovered. Both officers were killed. At this time the Victoria Cross (VC) was not awarded posthumously. This changed in the early 1900s when both Lieutenants were awarded posthumous Victoria Crosses for their bravery. The 2nd Battalion lost both its Colours at Isandhlwana though parts of the Colours—the crown, the pike and a colour case—were retrieved and trooped when the battalion was presented with new Colours in 1880.

The 24th had performed with distinction during the battle. The last survivors made their way to the foot of a mountain where they fought until they expended all their ammunition and were killed. The 24th Foot suffered 540 dead, including the 1st Battalion's commanding officer.

After the battle, some 4,000 to 5,000 Zulus headed for Rorke's Drift, a small missionary post garrisoned by a company of the 2/24th Foot, native levies and others under the command of Lieutenant Chard, Royal Engineers, the most senior officer of the 24th present being Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead. Two Boer cavalry officers, Lieutenants Adendorff and Vane, arrived to inform the garrison of the defeat at Isandhlwana. The Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton persuaded Bromhead and Chard to stay and the small garrison frantically prepared rudimentary fortifications.

The Zulus first attacked at 4:30 pm. Throughout the day the garrison was attacked from all sides, including rifle fire from the heights above the garrison, and bitter hand-to-hand fighting often ensued. At one point the Zulus entered the hospital, which was stoutly defended by the wounded inside until it was set alight and eventually burnt down. The battle raged on into the early hours of 23 January but by dawn the Zulu Army had withdrawn. Lord Chelmsford and a column of British troops arrived soon afterwards. The garrison had suffered 15 killed during the battle (two died later) and 11 defenders were awarded the Victoria Cross for their distinguished defense of the post, 7 going to soldiers of the 24th Foot.

54cm long inc haft read more

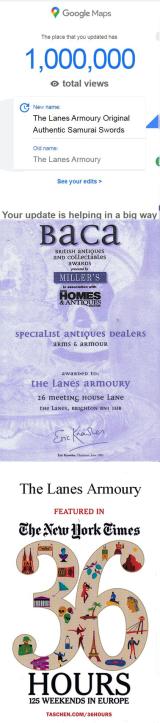

One Million Viewers!! Google Just Informed Us 1,000,000 People Searched To Find Our Location on Google Maps Since We Updated Our Company Entry Recently.

Google just let us know our updated Google entry just past the amazing 1,000,000 { one million } searches in order to find out our location in order to visit us here in Brighton, England.

Twenty Three Years Ago, After 80 Years Trading in Brighton, We Were Honoured by Being Nominated & Awarded by BACA, In The Best Antique & Collectables Shop In Britain Awards 2001

Presented by MILLER'S Antiques Guide, THE BBC, HOMES & ANTIQUES MAGAZINE, for the British Antique & Collectables Awards. The version of the antique dealers ‘Oscars’ of Britain.

It was a great honour for Mark and David, especially considering at the beginning of the new millennium, in the year 2000, there was over 7,000 established antique and collectors shops in the UK, according to the official Guide to the Antique Shops of Britain, 1999-2000, and we were nominated, and voted into in the top four in Britain.

We were also very kindly described and listed as one of the most highly recommended visitors attractions in the whole of Europe and the UK by nothing less than the 'New York Times ' within their travel guide "New York Times, 36 Hours, 125 Weekends in Europe read more

Price

on

Request

A 18th to Mid 19th Century Steel, Indo Persian, Double Crescent Blade Headed War Axe and Spike, Known as a Tabarzin

Of a type carried into battle by Indo-Persian/Mughal warriors. With engraved bird and floral decoration to the axe heads. Iron shaft.

The double head war axe with spike would have been a very effective battlefield weapon and had excellent balance.

The term tabar is used for axes originating from the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Armenia, India and surrounding countries and cultures. As a loanword taken through Iranian Scythian, the word tabar is also used in most Slavic languages as the word for axe.

The tabarzin (saddle axe) (Persian: تبرزین; sometimes translated "saddle-hatchet") is the traditional battle axe of Persia. It bears one or two crescent-shaped blades. The long form of the tabar was about seven feet long, while a shorter version was about three feet long or less. What makes the Persian axe unique is the very thin handle, which is very light and always metallic. The tabarzin was sometimes carried as a symbolic weapon by wandering dervishes (Muslim ascetic worshippers). The word tabar for axe was directly borrowed into Armenian as tapar (Armenian: տապար) from Middle Persian tabar, as well as into Proto-Slavonic as "topor" (*toporъ), the latter word known to be taken through Scythian, and is still the common Slavic word for axe.

A delightful example of a ceremonial axe in war axe form read more

495.00 GBP

Another Fabulous Christmas Gift Idea. A Superb Pair of Regency Silhouette Portraits of a Scottish Lady and Gentleman, Possibly by George Atkins

Circa 1815 to 1830 British School. The gentleman is holding his fouling piece, and wearing a kilt. The lady is holding what appears to be her prayer book. Both silhouettes are hand cut black paper aplied to an off-white card backing, emphasized with gold shadow highlights. Original Regency rosewood frames. A silhouette is the image of a person, animal, object or scene represented as a solid shape of a single colour, usually black, with its edges matching the outline of the subject. The interior of a silhouette is featureless, and the silhouette is usually presented on a light background, usually white, or none at all. The more expensive versions could have a gold highlight such as these have. The silhouette differs from an outline, which depicts the edge of an object in a linear form, while a silhouette appears as a solid shape. Silhouette images may be created in any visual artistic media, but were first used to describe pieces of cut paper, which were then stuck to a backing in a contrasting colour, and often framed.

Cutting portraits, generally in profile, from black card became popular in the mid-18th century, though the term silhouette was seldom used until the early decades of the 19th century, and the tradition has continued under this name into the 21st century. They represented an effective alternative to the portrait miniature, and skilled specialist artists could cut a high-quality bust portrait, by far the most common style, in a matter of minutes, working purely by eye. Other artists, especially from about 1790, drew an outline on paper, then painted it in, which could be equally quick.

From its original graphic meaning, the term silhouette has been extended to describe the sight or representation of a person, object or scene that is backlit, and appears dark against a lighter background. Anything that appears this way, for example, a figure standing backlit in a doorway, may be described as "in silhouette". Because a silhouette emphasises the outline, the word has also been used in the fields of fashion and fitness to describe the shape of a person's body or the shape created by wearing clothing of a particular style or period. 10.5 x 12.5 inches framed. Picture in the gallery of a drawing a Silhouette by Johann Rudolph Schellenberg (1740?1806). Light staining to the gentlemans white backing paper. read more

595.00 GBP

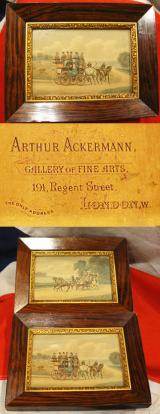

What a Superb Antique Christmas Gift Idea. A Pair of Simply Delightful Original Victorian Royal Mail Coaching Prints in Fine Rosewood Veneer Frames

With their original and super old retailer's labels of the most distinguished Arthur Ackerman Gallery of Fine Arts, 191 Regent St. London, W. A charming pair of original Victorian coloured prints in fine quality frames. 6.75 inches x 8.75 inches framed In the 18th century travel was hazardous to all. Highwaymen stalked the roads and those leading into London were said to be ‘infested’ with robbers. Romantic tales of masked, gallant gentleman were far from the truth: highwaymen were ruthless and deadly.

On 4 December 1775, a Norwich stagecoach was attacked by a gang of seven highwaymen. The guard shot three robbers before being killed and the coach robbed. Richard ‘Dick’ Turpin, a famous highwayman of the time, was known to torture his victims and would even kill one of his companions to aid his own escape.

‘… recommending the Guarding of all the Horse Mails, as a measure of national importance to which the Public in some degree conceived themselves entitled…’

Francis Freeling, Resident Surveyor, 14th March 1796

A plan was written to guard all horse mails, which included the arming of all guards. In doing so the Post Office would not only secure the vast property conveyed by horse, but also save the expenses incurred in prosecuting a robber. Furthermore, it would maintain regularity of service and eliminate what was seen as a disgrace to both the Office and to the nation.

Surveyors observed that the revenue lost to robbery was twice the sum it would cost to guard the mail: it was the obvious choice. In 1784, John Palmer introduced the first mail coach from Bristol to London. This faster and well-armed postal service proved to be a great deterrent to robbers, as they risked being shot or, if caught, tried and hanged. The first recorded robbery of a mail coach did not occur until 25 July 1786.

A letter to joint Postmaster Generals asking for the establishment of a regional mail coach was signed by over 100 people, whose businesses had been damaged due to the frequency of robberies. Mail coaches were a better way of securing the post’s safe passage, though there are a few recorded instances of attempted robberies even of them.

In January 1816, an Enniskillen coach was attacked and robbed by a gang of 14 men who had barricaded the road. The guards fired off all of their ammunition but the mail bags and weapons were all stolen. the Mail Guard was issued with a a pair of flintlock pistols read more

375.00 GBP

A Very Good Victorian 19th Century Royal Artillery Officer's Pouch

Patent leather with gilt badge of an artillery cannon. A cross belt is two connected straps worn across the body to distribute the weight of loads, carried at the hip, across the shoulders and trunk. It is similar to two shoulder belts joined with a single buckle at the center of the chest. The cross belt was predominantly used from the 1700s (American Revolutionary War) to the 1840s they were not part of a soldier's equipment in the American Civil War and Anglo-Zulu War/First Boer War.

For most line infantry, skirmishers, light infantry, grenadiers and guard regiments during much of Europe's Age of Gunpowder, either a cross belt or two shoulder belts were worn.citation needed One configuration for the belts would be the cartridge box on the right hip and sword scabbard on the left. Such equipment would be attached to the belt at its lowest point, where it rests on the hip. Officers almost never carried muskets or rifles, so they typically wore only one shoulder belt, such as for the pistol cartridge box or for a sabre scabbard. As officers were often aristocratic and used many independent symbols for their family, rank, and command, their uniforms and gear organisation could be highly variable.

For British infantry, the cross belt had a metal belt plate with the regiment of the soldier inscribed on it read more

245.00 GBP

A Superb Antique Historismus Armour Breastplate Stunningly Etched With Heraldic Beasts, The Form of Armour Worn by Conquistadors Officers and Commanders.

A beautiful piece of chest parade armour, with an etched crest of nobility comprising three winged Griffins and a central Lion rampant within a shield. The Griffin (or Gryphon) is a legendary creature with the body of a lion and the head and wings of an eagle. Combining the attributes of the "King of the Beasts" and the "King of the Air", it was thought to be especially powerful and majestic. A light armour breastplate, 16th century style in the manner of the 1550's, with old restoration, 19th century and earlier.

Parade armour became an elaborate and ornate Renaissance art form intended to both glorify war, and flatter the military prowess of the royal subject. Surviving examples include decorated shields, helmets, and full suits of armour. Delaune was an important contributor to the form, and Henry II of France commissioned a number of similar works, including a panel for his horse, and some bucklers (shields) now in the Louvre, both by Delaune. In addition surviving works for Henry include a full suit at the Museum of Ethnology, Last picture in the gallery is a painting by

Madeleine Boulogne (French, 1648–1710)

Titled;

Pieces of parade armour, a plumed helmet, a pistol in a case, a gilt ewer, a silver perfume burner, a jewellery box, a trumpet and a flag on a partly-draped cassone. 18.5 inches x 14.5 inches read more

1650.00 GBP