Antique Arms & Militaria

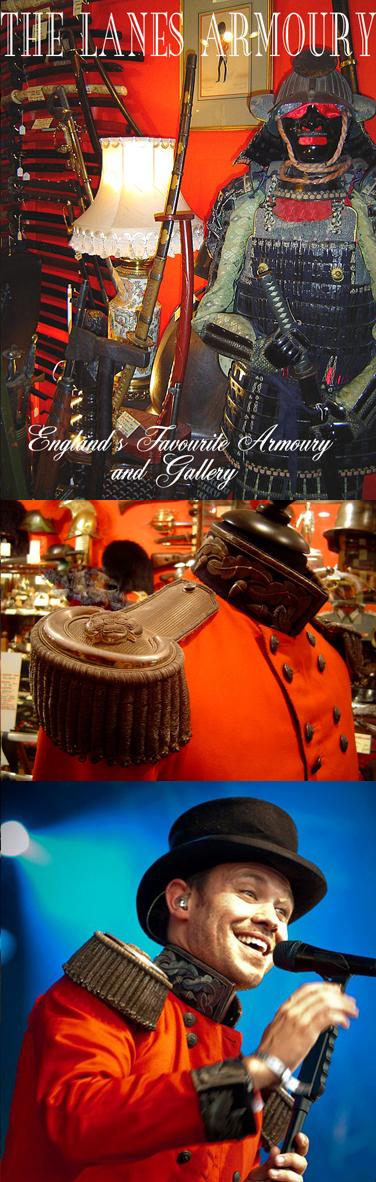

Welcome to The Lanes Armoury, Britain's Truly Magical Place, Where Thousands of Original & Breathtaking Wonders Are For Sale

Our beautiful pieces from history are not always just for looking at, some can still be enjoyed and worn for every one to see.

See our latest incredible 'Royal' daggers from the 17th century Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops) of the King of Sri Lanka. Occasionally, as we are Great Britain’s leading gallery of our kind, we have had had such knives, over the past 30 years, before, but nothing as fine as these museum grade examples, from the small collection we were thrilled to have acquired.

We have just also just added to the web store; a German colonels sword surrendered at the formal surrender of the German armed forces in May 1945 to Field Marshal Lord Montgomery, and a beautiful and magnificent samurai swords from the 1600's Tokugawa Shogunate period, one of the most fabulous samurai swords you might ever see. Plus, an Ancient Greek short sword or long dagger From The Greco-Persian Wars era, From the time of the Spartans at Thermopylae, to Alexander the Great's conquest of Persia & Egypt

We Are Not Just A Webstore, We Are Always Welcoming Thousands Personal Visitors To View or Buy our Museum Pieces in Our Gallery In Brighton, Every Day* {but Sunday}

Thousands of original, historic, ancient, antique and vintage collectables. For example; from Ancient Rome, China and Greece, to Medieval Japan, and Viking Europe. Covering British, European, and in fact, all worldwide eras of historical events from the past 4000 years, with antiquities, weaponry, armour, object d’art, militaria and fabulous books, from the Stone Age, the Bronze Age and the iron age, and right up to WW2.

Where else in the world could you find, under one roof, original artifacts, such as,; a mace and archer’s ring recovered from the site of Battle of Crecy, a sword of a British Admiral or notorious pirate fleet captain of the Golden Age of piracy of 17th century England, a battle mace, possibly once used by of one the personal guards in the service of the most famous Pharoah, Rameses the Great of Egypt, or, a museum quality 500 year old sword of a samurai clan Daimyo lord, and a pair of gold and enamel Art Deco 1920’s Magic Circle medals awarded to a friend of Harry Houdini. And all of the above, with many, many other Museum pieces, have been just been offered upon the site within the past couple of weeks.

Personalised and unique ‘Certificates of Authenticity’ can be supplied for every, single, purchase.

Our family have been personally serving the public in Brighton for several generations, in fact, for over 105 years.

* Opening hours Monday to Saturday 11.00am till 4.00pm, closed Sundays and Bank Holidays.

See in the gallery Will Young wearing one of our fabulous Victorian tunics, plus, James Marshall ‘Jimi’ Hendrix read more

Price

on

Request

A Breathtaking & Original Museum Piece. An Ancient Greek Leaf Shaped Sword or Long Dagger From The Greco-Persian Wars Era, From the Time of the Spartans at Thermopylae, To Alexander the Great's Conquest of Persia & Egypt

An original and most rare ancient Greek warrior's short sword or long dagger, circa 500 to 300 b.c. In superb excavated condition, and remarkable for its age, with light areas of encrustations and an overall delightful patina, all one piece cast construction.

Likely the short sword or long dagger of a warrior from the time of the Spartans at Thermopylae to Alexander the Great {son of Philip II of Macedon} and his renown conquests of the then known world.

Also as used at the Battle of Thermopylae which was fought between an alliance of Greek city-states, led by King Leonidas I of Sparta, and the Achaemenid Empire of Xerxes I.

It was fought over the course of three days, during the second Persian invasion of Greece. The battle took place simultaneously with the naval battle at Artemisium. It was held at the narrow coastal pass of Thermopylae ("The Hot Gates") in August or September 480 BC.

The Persian invasion was a delayed response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion of Greece, which had been ended by the Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. By 480 BC, Xerxes had amassed a massive army and navy and set out to conquer all of Greece. The Athenian politician and general Themistocles had proposed that the allied Greeks block the advance of the Persian army at the pass of Thermopylae, while simultaneously blocking the Persian navy at the Straits of Artemisium.

A Greek force of approximately 7,000 men marched north to block the pass in the middle of 480 BC. The Persian army was rumoured to have numbered over one million soldiers. Herodotus, a contemporary writer put the Persian army strength as one million and went to great pains to describe how they were counted in groups of ten thousand at a review of the troops. Simonides went as far as to put the Persian number at three million. Today, it is considered to have been much smaller. Scholars report various figures ranging between about 100,000 and 150,000 soldiers. The Persian army arrived at the pass in late August or early September. The vastly outnumbered Greeks held off the Persians for seven days (including three of battle) before the rear-guard was annihilated in one of history's most famous last stands. During two full days of battle, the small force led by Leonidas blocked the only road by which the massive Persian army could pass. After the second day, a local resident named Ephialtes betrayed the Greeks by revealing a small path used by shepherds. It led the Persians behind the Greek lines. Leonidas, aware that his force was being outflanked, dismissed the bulk of the Greek army and remained to guard their retreat with 300 Spartans and 700 Thespians. It has been reported that others also remained, including up to 900 helots and 400 Thebans. The remaining soldiers fought to the death. Most of the Thebans reportedly surrendered. Around 150 years later Alexander the Great, Greece’s most famous king created an Empire that still today resonates in its magnitude. Ancient Greek warriors were still using daggers such as this one. While Alexander's army mainly fielded Pezhetairoi (Foot Companions) as his main force, his army also included some classic Hoplites, either provided by the League of Corinth or from hired mercenaries. Beside these units, the Macedonians also used the so-called Hypaspists, an elite force of units possibly originally fighting as Hoplites and used to guard the exposed right wing of Alexander's phalanx. Today, Alexander the Great is still considered one of the most successful military leaders in history. His conquests shaped not just eastern and western culture but also the history of the world. Alexander was born July 20, 356 BC in Pella, a city in the Ancient Greek Kingdom of Macedonia. As the son of Philip II, King of Macedon, Alexander was raised as a noble Macedonian youth. Learning to read, play the lyre, ride, fight, and hunt were high priorities for Alexander.

As he got older, his father had the famous Aristotle tutor his son. His father knew he could no longer effectively challenge the mind and body of his son. Aristotle educated Alexander and his companions in various disciplines such as medicine, philosophy, morality, religion, logic, and art. Many of his study companions would later become generals in his army.

When King Philip was assassinated, Alexander ascended to the throne at the young age of 20. After quelling small uprisings and rebellions after his father’s death, Alexander began his campaign against the Persian Empire.

Crossing into Asia with over 100,000 men, he began his war against Persia which lasted more than seven years. Alexander displayed tactical brilliance in the fight against the Persian army, remaining undefeated despite having fewer soldiers.

His successes took him to the very edge of India, to the banks of the Ganges River. His armies feared the might of the Indian empires and mutinied, which marked the end of his campaign to the East. He had intended to march further into India, but he was persuaded against it because his soldiers wanted to return to their families.

Alexander died unexpectedly after his return to Babylon. Because his death was sudden and he did not name a successor to his throne, his empire fell into chaos as generals fought to take control.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery

A bronze short sword or long dagger with leaf-shaped blade, flat-section grip widening at the end. 630 grams, 38.5cm (15 1/4"). very fine condition for age. read more

2695.00 GBP

A Museum Piece, Antique 17th-18th Century Sinhalese Nobleman's Dagger Piha Kaetta, From The Royal Workshops of The King Of Kandy With Fabulous Gold Alloy, Silver, & Carved Black Coral Grip, and Very Unusually With its Original Scabbard.

The knife has being cleaned and conserved in the workshop

From our latest incredible collection of early 'Royal' daggers from the 17th century Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops) of the King of Kandy of Sri Lanka

From the sixteenth century, the Kandyan kingdom was drawn into the Wars of Kotte Succession after the Kingdom of Kotte was divided among three brothers. It was also at this time that the Portuguese Empire intruded into the internal affairs of Sri Lanka, establishing control over the maritime regions of the island and seeking to control its lucrative external trade. During this civil war the Kandyan kingdom almost lost its independence the Kingdom of Sitawaka who occupied it for a decade. The Crisis culminated in the collapse of the Kotte kingdom in 1597 and all of its successor states, including the Sitawaka kingdom. Kandy was the only independent Sinhalese kingdom to survive thus beginning the Kandyan period (1592–1815). Kandyan rulers, in an effort to protect their independence, alternated between resistance and diplomacy when dealing with the Europeans.

In the seventeenth century, the kingdom formed an alliance with the Dutch East India Company to expel the Portuguese from the island. Although the Portuguese were eventually removed, the Dutch double-crossed the Kandyans and retained control of the coastal regions and relations between Kandy and the Dutch became strained. The Kandyans and the Dutch would engage in two wars with the later resulting in loss of all of Kandy's remaining coastal territory, making it a landlocked country.

A single edged robust steel blade with fuller along the back edge. The forte and spine of the blade are heavily encrusted in silver and gold alloy with scrolling foliage, encased on each side with chased silver alloy bolster panels, over the base, decorated with finely chased floral and vine scrolling foliage, with finely carved black coral grip.

The hilt is finely carved and detailed with aliya-pata pattern hilt. The end is encased in a broad rounding of silver and gold alloy that has been chased in high relief with particularly fine Ceylonese scrolling foliage and flower motifs. From this is emitted a rounded tang button. In its wood scabbard with fluted finish and small wood part repaired

These fabulous and beautiful, elaborately decorated knives are the product of the Pattal-hatara (four royal workshops), the blades being supplied by smiths.

This was a mainly hereditary corporation of the best craftsmen who worked exclusively for the king in Kandy. Originally there was only one pattala but this was subsequently divided into sections which included a Randaku pattala (golden sword armoury or workshop). As well as being worn by courtiers, these knives were given by the king to nobles and to the temples. "The best of the higher craftsmen (gold and silversmiths, painters, and ivory carvers, etc.) working immediately for the king formed a close, largely hereditary, corporation of craftsmen called the Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops). They were named as follows; The Ran Kadu Golden Arms, the Abarana Regalia, the Sinhasana Lion Throne, and the Otunu Crown these men worked only for the King, unless by his express permission (though, of course, their sons or pupils might do otherwise); they were liable to be continually engaged in Kandy, while the Kottal-badda men were divided into relays, serving by turns in Kandy for periods of two months.

A related but less ornate example but without a scabbard currently is on display in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Also another, later but very similar to ours, with scabbard, in the same Museum, see below link,

Another example is in the Clive Collection (see Archer, 1987, p. 45 for an illustration.). The Clive example was first mentioned in inventories in 1775.

References

Caravana, J. et al, Rites of Power: Oriental Weapons: Collection of Jorge Caravana, Caleidoscopio, 2010.

Hales, R.,

Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour: A Lifetime’s Passion, Robert Hale CI Ltd, 2013.

De Silva, P.H.D.H & S. Wickramasinghe,

Ancient Swords, Daggers & Knives in Sri Lankan Museums, Sri Lanka National Museums, 2006.

Weereratne, N.,

Visions of an Island: Rare works from Sri Lanka in the Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Harper Collins, 1999.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O452562/knife-and-sheath/

Occasionally, as we are Great Britain’s leading gallery of our kind, we had had such knives, over the past 30 years, before, but nothing as fine as these museum grade examples, from the small collection we were thrilled to have acquired. read more

1895.00 GBP

A Superb & Very Rare Original Grouping, 5th to 7th Century Roman & Goth Period 'Ceremonially Folded' Sword, From a Pagan Ritual, A Warrior or Legionary's Spartha Sword, and War Shield Mounts

A very similar find of a Roman sword and shield boss was excavated in Greece last May, and caused a sensation and world news. The 'astonishing' findings have been shared by Errikos Maniotis, an archaeologist at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece, who believes the man likely served in the Roman imperial army.

'Usually, these types of swords were used by the auxiliary cavalry forces of the Roman army,' Maniotis told Live Science.

'Thus, we may say that the deceased, taking also into consideration the importance of the burial location, was a high-ranking officer of the Roman army.

It's rare to find a 'folded' sword in an urban landscape, let alone in this part of Europe, Maniotis pointed out. The term 'folded' sword describes that it has been believed to have been ceremonially killed and bent, in a pagan rite, to sacrifice the sword from current use, to represent a warrior passing into the afterlife, for it to be used in the afterlife by the warrior, and thus buried with his shield and offerings to the gods. Our sword group is around 1400 to 1600 years old. It was likely recovered more up to two centuries ago, probably a ‘Grand Tour’ find, from the area historically known as Merovingian Roman-Frankish Germany or France. The shield boss and handle have survived remarkably well, naturally the leather covered wooden shield body and sword hilt have rotted away over its 1200 plus years underground. The organic parts of shields and swords simply never survive this great period of time being buried. For example, we know not of a single complete Viking wooden shield in existence today, the only way we know today of their appearance is from ancient texts and poems that have survived. The spatha is a type of straight and long sword, measuring between 0.75 and 1 m , with a handle length between 18 and 20 cm , in use in the territory of the Roman Empire during the 1st to 6th centuries AD. Later swords, from the 6th to 10th centuries, like the Viking swords, are recognisable derivatives and sometimes subsumed under the term spatha.

The Roman spatha was used in war and in gladiatorial fights. The spatha of literature appears in the Roman Empire in the 1st century AD as a weapon used by presumably Germanic auxiliaries and gradually became a standard heavy infantry weapon, relegating the gladius to use as a light infantry weapon. The spatha apparently replaced the gladius in the front ranks, giving the infantry more reach when thrusting. While the infantry version had a long point, versions carried by the cavalry had a rounded tip that prevented accidental stabbing of the cavalryman's own foot or horse.

Archaeologically many instances of the spatha have been found in Britain and Germany. It was used extensively by Germanic warriors. It is unclear whether it came from the Pompeii gladius or the longer Celtic swords, or whether it served as a model for the various arming swords and Viking swords of Europe. The spatha remained popular throughout the Migration Period. It evolved into the knightly sword of the High Middle Ages by the 12th century. Picture of combating Frankish warrior knights using spartha and shields of the same type, from the Stuttgart Psalter.

The Merovingians were a Salian Frankish dynasty that ruled the Franks for nearly 300 years in a region known as Francia in Latin, beginning in the middle of the 5th century. Their territory largely corresponded to ancient Gaul as well as the Roman provinces of Raetia, Germania Superior and the southern part of Germania. The semi legendary Merovech was supposed to have founded the Merovingian dynasty, but it was his famous grandson Clovis I (ruled c.481-511) who united all of Gaul under Merovingian rule. Charles de Gaulle is on record as stating his opinion that "For me, the history of France begins with Clovis, elected as king of France by the tribe of the Franks, who gave their name to France. Before Clovis, we have Gallo-Roman and Gaulish prehistory. The decisive element, for me, is that Clovis was the first king to have been baptized a Christian. My country is a Christian country and I reckon the history of France beginning with the accession of a Christian king who bore the name of the Franks. The Merovingians are featured in the book The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail (1982) where they are depicted as descendants of Jesus, inspired by the "Priory of Sion" story developed by Pierre Plantard in the 1960s. Plantard playfully sold the story as non-fiction, giving rise to a number of works of pseudohistory among which The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail was the most successful. The "Priory of Sion" material has given rise to later works in popular fiction, notably The Da Vinci Code (2003), which mentions the Merovingians in chapter 60 . The ritual 'killing' of swords, such as bending or breaking have been found in thousands of examples of this practice across Europe, indicating that it was a ritual common to all the pan-Celtic tribes. However, although many theories have been postulated, for now the exact significance of this mysterious custom remains unclear. Some suggest it may be for all to know that the blade is not to recovered by grave robbers, or, possibly, the warrior or knight owner has been killed in battle, and thus his sword, as part of him, is also now dead. Or, maybe an offering to the gods of the afterlife. A Merovingian Frankish sword in 'un-killed' condition, is such a rare piece to survive to today, would likely be valued comfortably into five figures £12,000 plus. In May 2021 An iron sword deliberately bent as part of a pagan ritual has been discovered in a Roman soldier's grave in Greece, an archaeologist has revealed.

The deformed or 'folded' sword was buried with an as yet unidentified soldier about 1,600 years ago in the Greek city of Thessaloniki.

His 'arch-shaped' grave was found in the underground remains of a basilica – a large public building and place of worship – dating from the fifth century AD. 'Folded swords are usually excavated in sites in Northern Europe,' he said.

'It seems that Romans didn't practise it, let alone when the new religion, Christianity, dominated, due to the fact that this ritual was considered to be pagan.'

Archaeologists are yet to assess the remains of the soldier, described as likely a 'Romanized Goth or from any other Germanic tribe who served as a mercenary'.

'We don't know anything about his profile – age of death, cause of death, possible wounds that he might have from the wars he fought,' Maniotis said.

The soldier's grave was one of seven found in the basilica, but not all of them were found containing artefacts. in the third century A.D., the Goths launched a series of raids into the Roman Empire. “The first known attack came in 238, when Goths sacked the city of Histria at the mouth of the river Danube. A series of much more substantial land incursions followed a decade later,” writes Peter Heather, a professor at King’s College London, in his book “The Goths” (Blackwell Publishers, 1996).

He notes that in A.D. 268, a massive expedition of Goths, along with other groups also called barbarians, broke into the Aegean Sea, wreaking havoc. They attacked a number of settlements, including Ephesus (a city in Anatolia inhabited by Greeks), where they destroyed a temple dedicated to the goddess Diana.

“The destruction wrought by this combined assault on land and sea were severe, and prompted a fierce Roman response. Not only were the individual groups defeated, but no major raid ever again broke through the Dardanelles,” writes Heather.

The Goths' tumultuous relationship with Rome would continue into the fourth century. While Goths served as Roman soldiers, and trade took place across the Danube River, there was plenty of conflict.

Heather notes that a Gothic group called the Tervingi intervened in Roman imperial politics, supporting two unsuccessful claimants to the emperorship. In A.D. 321, they supported Licinius against Constantine, and in A.D. 365, they supported Procopius against Valens. In both instances this backfired, with Constantine and Valens launching attacks against the Tervingi after becoming emperor.

As contact with Rome intensified, a form of Christianity known as Arianism spread among the Goths.

“In the 340s, the Arian Gothic bishop Ulfilas or Wulfila (d. 383) translated the Bible into the Gothic language in a script based chiefly upon the uncial Greek alphabet and said to have been invented by Ulfilas for the purpose,” writes Robin Sowerby, a lecturer at the University of Stirling, in an article in the book “A New Companion to the Gothic” (Wiley, 2012).

In time, the Goths would adopt the Catholic form of Christianity that came to be used in Rome. ; From a private collection of an English gentleman acquired in the 1940's. As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity. Almost every iron weapon that has survived today from this era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one, because only the swords of kings, that have been preserved in national or Royal collections are today still in a relative good state and condition. We show in the gallery two photos of the excavated Roman's tomb in Thessaloniki, and the Roman's folded spartha sword. In the photo of the tomb interior one can plainly see the folded sword and shield boss, the shield boss has been crushed flat. Another photograph is of the exhibit in the museum of Nuremberg Germany showing another original spartha sword unfolded and a fully formed shield boss, both are extremely similar to ours.

A sword was still so valued in the much later Norse society that good blades were prized by successive generations of warriors. There is even some evidence from Viking burials for the deliberate and possibly ritual "killing" of swords, a ritual from ancient times, which still involved the blade being bent so that it was unusable. Because Vikings were often buried with their weapons, the "killing" of swords may have served two functions, namely a ritualistic function in retiring a weapon with a warrior, and a practical one in deterring any grave robbers from disturbing the burial in order to get one of these costly weapons. Indeed, archaeological finds of the bent and brittle pieces of metal sword remains testify to the regular burial of Vikings with weapons, as well as the habitual "killing" of sword read more

4950.00 GBP

Antique Museum Worthy 17th-18th Century Sinhalese Nobleman's Dagger Piha Kaetta, From The Royal Workshops of The King Of Kandy, Sri Lanka, With Fabulous Chisseled,Engraved Gold Alloy, Silver, & Carved Black Coral Grip

A most stunning, ornate, pihas, and made exclusively by the Pattal Hattara (The Four Workshops). They were employed directly by the Kings of Kandy. Kandy, the independent kingdom, that was first established by King Wickramabahu (1357-1374 AD).

From our latest incredible collection of early 'Royal' daggers from the 17th century Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops) of the King Kandy of Sri Lanka. Each one a masterpiece of the early craftsman’s art

The last Kandyan king was in the early 1800's, and the workshops are no longer in existence today.

From these knives there are all transitions to the finest versions of nobles and princes, the most elaborate and costly of silver or gold inlaid and overlaid knives worn by the greatest chiefs as a part of their formal dress. The workmanship of many of these is most exquisite but this fine work is done rather by the higher craftsmen, the silversmiths and ivory carvers, than by the mere blacksmith. Many of the best knives were made in the Four Workshops, such as is this example, the blades being supplied to the silversmith by the blacksmiths.

"The best of the higher craftsmen (gold and silversmiths, painters, and ivory carvers, etc.) working immediately for the king formed a close, largely hereditary, corporation of craftsmen called the Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops). They were named as follows; The Ran Kadu Golden Arms, the Abarana Regalia, the Sinhasana Lion Throne, and the Otunu Crown these men worked only for the King, unless by his express permission (though, of course, their sons or pupils might do otherwise); they were liable to be continually engaged in Kandy, while the Kottal-badda men were divided into relays, serving by turns in Kandy for periods of two months. The Kottal-badda men in each district were under a foreman (mul-acariya) belonging to the Pattal-hatara. Four other foremen, one from each pattala, were in constant attendance at the palace.This beautiful noble's dagger is stunningly decorated with veka deka liya vela double curve vine motif and the flower motif sina mal, and a bold vine in damascene silver. The blade is traditonal iron and the hilt beautifully carved black coral

From the sixteenth century, the Kandyan kingdom was drawn into the Wars of Kotte Succession after the Kingdom of Kotte was divided among three brothers. It was also at this time that the Portuguese Empire intruded into the internal affairs of Sri Lanka, establishing control over the maritime regions of the island and seeking to control its lucrative external trade. During this civil war the Kandyan kingdom almost lost its independence the Kingdom of Sitawaka who occupied it for a decade. The Crisis culminated in the collapse of the Kotte kingdom in 1597 and all of its successor states, including the Sitawaka kingdom. Kandy was the only independent Sinhalese kingdom to survive thus beginning the Kandyan period (1592–1815). Kandyan rulers, in an effort to protect their independence, alternated between resistance and diplomacy when dealing with the Europeans.

In the seventeenth century, the kingdom formed an alliance with the Dutch East India Company to expel the Portuguese from the island. Although the Portuguese were eventually removed, the Dutch double-crossed the Kandyans and retained control of the coastal regions and relations between Kandy and the Dutch became strained. The Kandyans and the Dutch would engage in two wars with the later resulting in loss of all of Kandy's remaining coastal territory, making it a landlocked country.

A related but less ornate example also without a scabbard currently is on display in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Another example is in the Clive Collection (see Archer, 1987, p. 45 for an illustration.). The Clive example was first mentioned in inventories in 1775.

References

Caravana, J. et al, Rites of Power: Oriental Weapons: Collection of Jorge Caravana, Caleidoscopio, 2010.

Hales, R.,

Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour: A Lifetime’s Passion, Robert Hale CI Ltd, 2013.

De Silva, P.H.D.H & S. Wickramasinghe,

Ancient Swords, Daggers & Knives in Sri Lankan Museums, Sri Lanka National Museums, 2006.

Weereratne, N.,

Visions of an Island: Rare works from Sri Lanka in the Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Harper Collins, 1999.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O452562/knife-and-sheath/

Occasionally, as we are Great Britain’s leading gallery of our kind, we had had such knives, over the past 30 years, before, but nothing as fine as these museum grade examples, from the small collection we were thrilled to have acquired. read more

1495.00 GBP

A Most Beautiful and Intriguing, Early, Possibly 17th Century, Carved Lion Head Sinhalese Simha Makkara Lionhead Hilted, Tail-Bladed Knife

A large knife version of a Sinhalese early kastane short sword.

Traces of an early armourer's stamp at the ricasso of the blade, carved hardwood hilt in the form of a Sinhalese simha lion. The hilt has a pair of rivets through which the blade tang is held in place, and the rivet heads have copper rosette collars, very similar to the rosettes found on 17th century cabassat helmet rivets. A wide blade with an unusual recurved tail, and a single cutting edge. It is of a most unusual form and may for sacrificial purposes, or, a ceremonial implement of another function entirely. We feel it may be Sinhalese, by the hilt design, possible even loosely based on a very large piha kaetta knife.

Curiously it is incredibly similar to artefacts of the early pre-Colombian Central American period, such as Incan or Mayan. 13.5 inches long overall. read more

365.00 GBP

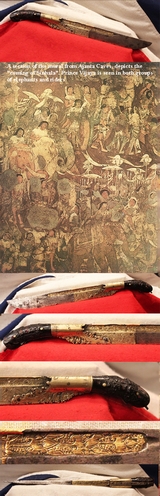

A Late 1600’s to 1700’s Very Fine Museum Grade, Black Coral Handled Sinhalese King’s or Noble’s Knife. A Royal Piha-Kaetta (Pihiya) With Finest Chisseled Silver And Gold. From The King of Kandy’s Workshop

The knife is being artisan conservator cleaned and conserved in the workshop, it is photographed here pre-conservation at present

A Fine Sinhalese Knife Piha-Kaetta (Pihiya) from Sri Lanka, Late 17th early 18th Century.

From our latest incredible collection of early 'Royal' daggers from the 17th century Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops) of the King of Kandy of Sri Lanka. Each one a masterpiece of the early craftsman’s art

From the sixteenth century, the Kandyan kingdom was drawn into the Wars of Kotte Succession after the Kingdom of Kotte was divided among three brothers. It was also at this time that the Portuguese Empire intruded into the internal affairs of Sri Lanka, establishing control over the maritime regions of the island and seeking to control its lucrative external trade. During this civil war the Kandyan kingdom almost lost its independence the Kingdom of Sitawaka who occupied it for a decade. The Crisis culminated in the collapse of the Kotte kingdom in 1597 and all of its successor states, including the Sitawaka kingdom. Kandy was the only independent Sinhalese kingdom to survive thus beginning the Kandyan period (1592–1815). Kandyan rulers, in an effort to protect their independence, alternated between resistance and diplomacy when dealing with the Europeans.

In the seventeenth century, the kingdom formed an alliance with the Dutch East India Company to expel the Portuguese from the island. Although the Portuguese were eventually removed, the Dutch double-crossed the Kandyans and retained control of the coastal regions and relations between Kandy and the Dutch became strained. The Kandyans and the Dutch would engage in two wars with the later resulting in loss of all of Kandy's remaining coastal territory, making it a landlocked country.

This Pihiya is a very well known form of early Ceylonese royal knife, with a straight-backed blade and a curved cutting edge.

The Pihiya Handle and part of the blade are beautifully and finely engraved and decorated with delicate tendrils, the powerful hilt is made out of different combinations of materials such as Gold, Silver, Brass, Copper, Rock Crystal, Ivory, Horn, Black Coral Steel and Wood. Sometimes the Gold or Silver mounts extend down halfway the blade.

Handles were made in a certain and very distinctive form, occasionally they were made in the form of serpentines or a mythical creature’s head, most similar to this stunning piece.

The Kaetta means a beak or billhook, it is a similar but larger knife to the Pihiya, it has a blade with a carved back and a straight cutting edge that curves only towards the tip.

The finest examples were made at the four workshop (Pattal-Hatara), where a selected group of craftsmen worked exclusively for the King and his court, and were bestowed to nobles and officials together with the kasthan? and a cane as a sign of rank and / or office. Others were presented as diplomatic gifts. Many of the best knives were doubtless made in the Four Workshops, such as is this example, the blades being supplied to the silversmith by the blacksmiths.

"The best of the higher craftsmen (gold and silversmiths, painters, and ivory carvers, etc.) working immediately for the king formed a close, largely hereditary, corporation of craftsmen called the Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops). They were named as follows; The Ran Kadu Golden Arms, the Abarana Regalia, the Sinhasana Lion Throne, and the Otunu Crown these men worked only for the King, unless by his express permission (though, of course, their sons or pupils might do otherwise); they were liable to be continually engaged in Kandy, while the Kottal-badda men were divided into relays, serving by turns in Kandy for periods of two months. The Kottal-badda men in each district were under a foreman (mul-acariya) belonging to the Pattal-hatara. Four other foremen, one from each pattala, were in constant attendance at the palace. Prince Vijaya was a legendary king of Sri Lanka, mentioned in the Pali chronicles, including Mahavamsa. He is the first recorded King of Sri Lanka. His reign is traditionally dated to 543 -505 bc. According to the legends, he and several hundred of his followers came to Lanka after being expelled from an Indian kingdom. In Lanka, they displaced the island's original inhabitants (Yakkhas), established a kingdom and became ancestors of the modern Sinhalese people.

A related but less ornate example but without a scabbard currently is on display in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Another example is in the Clive Collection (see Archer, 1987, p. 45 for an illustration.). The Clive example was first mentioned in inventories in 1775.

References

Caravana, J. et al, Rites of Power: Oriental Weapons: Collection of Jorge Caravana, Caleidoscopio, 2010.

Hales, R.,

Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour: A Lifetime’s Passion, Robert Hale CI Ltd, 2013.

De Silva, P.H.D.H & S. Wickramasinghe,

Ancient Swords, Daggers & Knives in Sri Lankan Museums, Sri Lanka National Museums, 2006.

Weereratne, N.,

Visions of an Island: Rare works from Sri Lanka in the Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Harper Collins, 1999.

https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O452562/knife-and-sheath/

Occasionally, as we are Great Britain’s leading gallery of our kind, we had had such knives, over the past 30 years, before, but nothing as fine as these museum grade examples, from the small collection we were thrilled to have acquired.

13 inches long overall read more

1795.00 GBP

A Finest Museum Piece. A Most Beautiful and Early Black Coral Handle, inlaid With Engraved Silver Banding and Four Rubies. Gold Alloy Mounted Sinhalese King's Knife 'Piha-Kaetta' (Pihiya)

From our latest incredible collection of early 'Royal' daggers from the 17th century Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops) of the King Kandy of Sri Lanka. Each one a masterpiece of the early craftsman’s art.

A Fine Sinhalese Knife Piha-Kaetta (Pihiya) from Sri Lanka, Late 17th early 18th Century. Stunningly decorated with gold alloy, silver and what appear to rubies. The gold alloy is incredibly floridly patterned and fully engraved with great skill. This early royal dagger is truly a joy to behold.

The Pihiya is a very well known Ceylonese highest status knife, made for Sri lankan royalty, with a straight-backed blade and a curved cutting edge.

The Pihiya handle and part of the blade are beautifully and finely engraved and decorated with delicate tendrils, the powerful hilt is made out of different combinations of materials such as gold, silver, brass, horn, black coral inlaid with rubies and a steel blade. Sometimes the gold or silver mounts extend down halfway the blade as does this wonderful example.

Handles were made in a certain and very distinctive form, occasionally they were made in the form of serpentines or a mythical creature's head, similar to this beauty.

The Kaetta means a beak or billhook, it is a similar but larger knife to the Pihiya, it has a blade with a carved back and a straight cutting edge that curves only towards the tip.

The finest examples were made at the four workshop (Pattal-Hatara), where a selected group of craftsmen worked exclusively for the King and his court, and were bestowed to nobles and officials together with the kasthan and a cane as a sign of rank and / or office. Others were presented as diplomatic gifts. Many of the best knives were doubtless made in the Four Workshops, such as is this example, the blades being supplied to the silversmith by the blacksmiths.

"The best of the higher craftsmen (gold and silversmiths, painters, and ivory carvers, etc.) working immediately for the king formed a close, largely hereditary, corporation of craftsmen called the Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops). They were named as follows; The Ran Kadu Golden Arms, the Abarana Regalia, the Sinhasana Lion Throne, and the Otunu Crown these men worked only for the King, unless by his express permission (though, of course, their sons or pupils might do otherwise); they were liable to be continually engaged in Kandy, while the Kottal-badda men were divided into relays, serving by turns in Kandy for periods of two months. The Kottal-badda men in each district were under a foreman (mul-acariya) belonging to the Pattal-hatara. Four other foremen, one from each pattala, were in constant attendance at the palace. Prince Vijaya was a legendary king of Sri Lanka, mentioned in the Pali chronicles, including Mahavamsa. He is the first recorded King of Sri Lanka. His reign is traditionally dated to 543-505 bce. According to the legends, he and several hundred of his followers came to Lanka after being expelled from an Indian kingdom. In Lanka, they displaced the island's original inhabitants (Yakkhas), established a kingdom and became ancestors of the modern Sinhalese people.

A related but less ornate example but without a scabbard currently is on display in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Another example is in the Clive Collection (see Archer, 1987, p. 45 for an illustration.). The Clive example was first mentioned in inventories in 1775.

References

Caravana, J. et al, Rites of Power: Oriental Weapons: Collection of Jorge Caravana, Caleidoscopio, 2010.

Hales, R.,

Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour: A Lifetime’s Passion, Robert Hale CI Ltd, 2013.

De Silva, P.H.D.H & S. Wickramasinghe,

Ancient Swords, Daggers & Knives in Sri Lankan Museums, Sri Lanka National Museums, 2006.

Weereratne, N.,

Visions of an Island: Rare works from Sri Lanka in the Christopher Ondaatje Collection, Harper Collins, 1999.

Overall 32 cm's long,

Occasionally, as we are Great Britain’s leading gallery of our kind, we had had such knives, over the past 30 years, before, but nothing as fine as these museum grade examples, from the small collection we were thrilled to have acquired. read more

1725.00 GBP

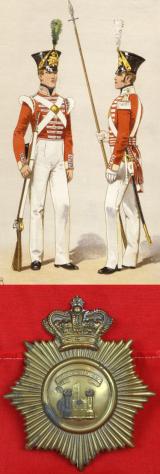

An Incredibly Rare & Historically Significant. An Early19th Century, Georgian to William IVth Irish, Crum Castle Infantryman's Large Shako Helmet Plate

This is a superb, and incredibly desirable large Bell-Top Shako helmet plate, from one of the small Irish Militia of the early 19th century. Their motto was 'Rebels Lie Down'.

Surviving artefacts of this militia are so scarce that we know of only one other surviving piece of early uniform militaria, a shoulder belt plate, regimentally named and also bearing their motto.

Early 19th century Irish Militia helmet plates are incredibly rare in their own right, and both highly prized and very collectable indeed.

Crum Castle was the alternative old spelling of Crom Castle, County Fermanagh. Although the Yeomanry’s official existence ended in 1834, the last rusty muskets were not removed from their dusty stores till the early 1840s. With unintentional but obvious symbolism, they were escorted to the ordnance stores by members of the new constabulary. Although gone, the Yeomen were most certainly not forgotten. For one thing, they were seen as the most recent manifestation of a tradition of Protestant self-defence stretching back to plantation requirements of armed service from tenants then re-surfacing in different forms such as the Williamite county associations, the eighteenth-century Boyne Societies, anti-Jacobite associations of 1745 and the Volunteers. Such identification had been eagerly promoted. At the foundation of an Apprentice Boys’ club in 1813, Colonel Blacker, a Yeoman and Orangeman, amalgamated the siege tradition, the Yeomanry and 1798 in a song entitled The Crimson Banner:

Again when treason maddened round,

and rebel hordes were swarming,

were Derry’s sons the foremost found,

for King and Country arming.

Moreover, the idea of a yeomanry remained as a structural template for local, gentry-led self-defence, particularly in Ulster. When volunteering was revived in Britain in 1859, northern Irish MPs like Sharman Crawford tried unsuccessfully to use the Yeomanry precedent to get similar Irish legislation. Yeomanry-like associations were mooted in the second Home Rule crisis of 1893. The Ulster Volunteer Force of 1911-14—often led by the same families like Knox of Dungannon—defined their role like Yeomen, giving priority to local defence and exhibiting great reluctance to leave their own districts for training in brigades. Two loop mounts one with old re-bedding 6.25 inches high. read more

1895.00 GBP

A Superb Original Imperial Roman Legionary's "Whistling" Sling Bullet Circa 1st to 2nd century AD.

Identical to the few found at an archaeological dig at a Roman Fort site in southwestern Scotland a few years ago, and one of a very small collection of fine original sling bullets of antiquity we acquired.

Over 1,800 years ago, Roman troops used "whistling" sling bullets as a "terror weapon" against their barbarian foes, such as were in Scotland and the Celts in England, according to archaeologists who found the cast lead bullets at a site in Scotland.

Weighing about 1 ounce (30 grams), each of the bullets had been drilled with a 0.2-inch (5 millimeters) hole that the researchers think was designed to give the soaring bullets a sharp buzzing or whistling noise in flight.

The bullets were found recently at Burnswark Hill in southwestern Scotland, where a massive Roman attack against native defenders in a hilltop fort took place in the second century A.D. These holes converted the bullets into a "terror weapon," said archaeologist John Reid of the Trimontium Trust, a Scottish historical society directing the first major archaeological investigation in 50 years of the Burnswark Hill site.

"You don't just have these silent but deadly bullets flying over; you've got a sound effect coming off them that would keep the defenders' heads down," Reid told Live Science. "Every army likes an edge over its opponents, so this was an ingenious edge on the permutation of sling bullets."

The whistling bullets were also smaller than typical sling bullets, and the researchers think the soldiers may have used several of them in their slings — made from two long cords held in the throwing hand, attached to a pouch that holds the ammunition — so they could hurl multiple bullets at a target with one throw.

"You can easily shoot them in groups of three of four, so you get a scattergun effect," Reid said. "We think they're for close-quarter skirmishing, for getting quite close to the enemy." Onasandrius wrote the 1st C. BC, in his book "Strategy". "The Sling is the deadly weapon used by light infantry because lead is of the same colour as the air and therefore not visible, thus the impact is unexpected and not only smites hard, but the bullet penetrates deeply into the victims flesh". Used by Roman auxiliary troops like Greeks, Sicilians, North Africans, but after the Roman conquest of the Balearic Islands elite slingers were always the Balearic that fought in the legions of Julius Caesar.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

220.00 GBP