Antique Arms & Militaria

A Most Intriguing, Early, Wide Bladed Mayan or Aztec Form Sacrificial Knife, Beautifully Carved Head of Possibly Vucub Caquix or Quetzalcoatl The Wind Spouting God, Upon the Stag-Horn Hilt

Acquired from an early, rare edged weapon collector,

An early antique wide hammer forged blade in an an almost Bowie style, with its clipped back tip form, and a single cutting edge. It is of a most unusual form of hilt with a large bladed knife, and may for tribal sacrificial purposes, or, a tribal ceremonial knife.

The carving is very reminiscent of the Mayan, Incan and Aztec culture, but some knives of this form can be little like those from Bali. The Aztec looking wind spouting snake head demon, is rather intriguing, and superbly executed, but as this is the first we have seen quite like this we can only suggest the comparisons we have seen in the past 50 years.

Vucub-Caquix is the name of a bird demon defeated by the Hero Twins of a Kʼicheʼ-Mayan myth preserved in an 18th-century document, entitled ʼPopol Vuhʼ. The episode of the demon's defeat was already known in the Late Preclassic Period, before the year 200 AD. He was also the father of Zipacna, an underworld demon deity, and Cabrakan, the Earthquake God.

To the Aztecs, Quetzalcoatl was, as his name indicates, a feathered serpent. He was a creator deity having contributed essentially to the creation of mankind. He also had anthropomorphic forms, for example in his aspects as Ehecatl the wind god. Among the Aztecs, the name Quetzalcoatl was also a priestly title, as the two most important priests of the Aztec Templo Mayor were called "Quetzalcoatl Tlamacazqui". In the Aztec ritual calendar, different deities were associated with the cycle-of-year names: Quetzalcoatl was tied to the year Ce Acatl (One Reed), which correlates to the year 1519.

One hand coloured page in the gallery is Quetzalcoatl as depicted in the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, there are also photos of original Mayan and Aztec stone carvings, depicting the god Quetzalcoatl. One can easily see the similarity to the carving depicted on the knife's hilt to these stone carvings

16 inches long overall. read more

465.00 GBP

A Late 1600’s Very Fine Black Coral Handled Sinhalese King’s or Noble’s Knife. A Royal Piha-Kaetta (Pihiya)

A Fine Sinhalese Knife Piha-Kaetta (Pihiya) from Sri Lanka, Late 17th early 18th Century

This Pihiya is a very well known form of early Ceylonese royal knife, with a straight-backed blade and a curved cutting edge.

The Pihiya Handle and part of the blade are beautifully and finely engraved and decorated with delicate tendrils, the powerful hilt is made out of different combinations of materials such as Gold, Silver, Brass, Copper, Rock Crystal, Ivory, Horn, Black Coral Steel and Wood. Sometimes the Gold or Silver mounts extend down halfway the blade.

Handles were made in a certain and very distinctive form, occasionally they were made in the form of serpentines or a mythical creature’s head, most similar to this stunning piece.

The Kaetta means a beak or billhook, it is a similar but larger knife to the Pihiya, it has a blade with a carved back and a straight cutting edge that curves only towards the tip.

The finest examples were made at the four workshop (Pattal-Hatara), where a selected group of craftsmen worked exclusively for the King and his court, and were bestowed to nobles and officials together with the kasthan? and a cane as a sign of rank and / or office. Others were presented as diplomatic gifts. Many of the best knives were doubtless made in the Four Workshops, such as is this example, the blades being supplied to the silversmith by the blacksmiths.

"The best of the higher craftsmen (gold and silversmiths, painters, and ivory carvers, etc.) working immediately for the king formed a close, largely hereditary, corporation of craftsmen called the Pattal-hatara (Four Workshops). They were named as follows; The Ran Kadu Golden Arms, the Abarana Regalia, the Sinhasana Lion Throne, and the Otunu Crown these men worked only for the King, unless by his express permission (though, of course, their sons or pupils might do otherwise); they were liable to be continually engaged in Kandy, while the Kottal-badda men were divided into relays, serving by turns in Kandy for periods of two months. The Kottal-badda men in each district were under a foreman (mul-acariya) belonging to the Pattal-hatara. Four other foremen, one from each pattala, were in constant attendance at the palace. Prince Vijaya was a legendary king of Sri Lanka, mentioned in the Pali chronicles, including Mahavamsa. He is the first recorded King of Sri Lanka. His reign is traditionally dated to 543?505 bce. According to the legends, he and several hundred of his followers came to Lanka after being expelled from an Indian kingdom. In Lanka, they displaced the island's original inhabitants (Yakkhas), established a kingdom and became ancestors of the modern Sinhalese people. 13 inches long overall read more

795.00 GBP

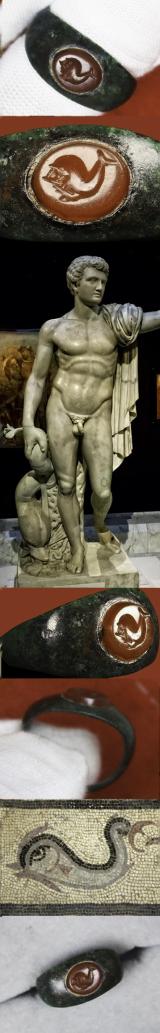

An Absolutely Beautiful Original 2nd Century Imperial Roman Officer or Noble's Carved Intaglio, Carnelian Gem Stone, Status Seal Ring, Depicting a Dolphin. Originally Worn in the Roman Empire's of Trajan to Commodus

In Rosemary Sutcliff’s 'Eagle of the Ninth' series of books, a similar Dolphin ring was first owned by a Roman soldier and passed down the family over the centuries.

Made and worn during the reigns of;

Emperor Trajan

Emperor Hadrian

Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Emperor Lucius Aurelius Verus

Emperor Commodus Antoninus

The carvings on rings and seals are known as Intaglio, and a seal ring was part of Roman society for nobles, military officers and citizens. They were personal signets, and the more valuable were made from a small gemstone, with a design cut into the surface by skilled craftsmen, and usually set within a ring. They were used to seal important documents, and objects by making an impression on soft clay or wax. Wearing a carved carnelian signet ring immediately showed that you were of rank, and thus had status, wealth and influence. Some surviving rings have been found across Roman Britain, in towns and military sites alike, including two at the Waddon Hill former Roman military fort site..

Dolphins, like those seen on the Venus Mosaic found at Kingscote in Gloucestershire, are a fairly popular image in Roman art. They have a rich background in Greek and Roman mythology, literature, and folklore. They were often included in sculptures to improve the stability of the main figures!

Dolphins are featured in many Greek and Roman myths. Here, they are symbols of romance, illustrating the theme established by the depiction of Venus, the Roman Goddess of Love, in the central roundel of the mosaic. The presence of these dolphins alongside Venus also serves as a reminder of the myth that Venus was born from the sea, famously depicted in Botticelli’s late fifteenth century painting ‘The Birth of Venus’.

Their association with Venus is by no means their only significance in Greek and Roman mythology. In the sixth/seventh century B.C. ‘Homeric Hymns’, Dionysus, the Greek God of Wine and Theatre (who later became Bacchus in Roman mythology), was kidnapped by pirates. He turned into a lion to punish the kidnappers and, terrified, they jumped overboard. When they hit the water, Dionysus turned them into dolphins. The ‘Homeric Hymns’ also describe Apollo, a Greek and Roman God, turning into a dolphin to guide a ship into harbour. Another myth tells that Apollo’s son, Eikadios, was shipwrecked and carried to shore by a dolphin. This is one of many myths about dolphins rescuing drowming men, or bringing bodies back to shore for burial.

Dolphins are also often associated with minor sea deities. The Roman author Statius wrote in his first century A.D. epic poem ‘Achilleid’ that the sea-nymph Thetis rode a chariot through the sea that was pulled by two dolphins. Similarly, Philostratus’ ‘Imagines’describes a scene in which the one-eyed cyclops Polyphemus falls in love with the sea-nymph Galatea while she is riding four dolphins.

3/4 of an inch across. read more

745.00 GBP

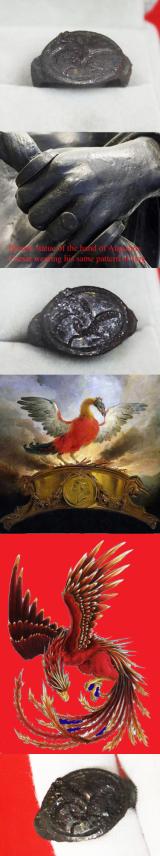

A Superb Roman 1900-2000 Year Old 'Status' Seal Ring, Intaglio, Stylized Engraved, with a Mythological Scene of The Pheonix In Flight. From The Time Of the Divine Augustus, The First Emperor of Rome

A superb Henig type Xb ring. Wide oval bezel affixed to flattened shoulders engraved copper bronze alloy with gilt highlights. Almost identical shape and form to one found in the UK near Hadrian's Wall. and another similar ring, with the very same style of workmanship and engraving from the era, was discovered 50 years ago, and believed to be once the ring of the infamous Pontius Pilate, the Governor of Judea for Rome

The Greek myth of the Pheonix in a nest of flames was set down in Ancient Rome by the great poet Ovid,

In Ovid's, Metamorphoses 15. 385 ff (trans. Melville) (Roman epic C1st B.C. to C1st A.D.) :

"These creatures other races of birds all derive their first beginnings from others of their kind. But one alone, a bird, renews and re-begets itself--the Phoenix of Assyria, which feeds not upon seeds or verdure but the oils of balsam and the tears of frankincense. This bird, when five long centuries of life have passed, with claws and beak unsullied, builds a nest high on a lofty swaying palm; and lines the nest with cassia and spikenard and golden myrrh and shreds of cinnamon, and settled there at ease and, so embowered in spicy perfumes, ends his life's long span. Then from his father's body is reborn a little Phoenix, so they say, to live the same long years. When time has built his strength with power to raise the weight, he lifts the nest--the nest his cradle and his father's tomb--as love and duty prompt, from that tall palm and carries it across the sky to reach the Sun's great city i.e. Heliopolis in Egypt, and before the doors of the Sun's holy temple lays it down."

Publius Ovidius Naso, 21 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the three canonical poets of Latin literature. The Imperial scholar Quintilian considered him the last of the Latin love elegists. Although Ovid enjoyed enormous popularity during his lifetime, the emperor Augustus exiled him to Tomis, the capital of the newly-organised province of Moesia, on the Black Sea, where he remained for the last nine or ten years of his life. Ovid himself attributed his banishment to a "poem and a mistake", but his reluctance to disclose specifics has resulted in much speculation among scholars.

Today, Ovid is most famous for the Metamorphoses, a continuous mythological narrative in fifteen books written in dactylic hexameters.

A ring discovered 50 years ago is now believed to possibly be the ring of Pontius Pilate himself, and it was the same copper-bronze form ring as is this one. See its image in the gallery, with a detailed drawing of the traditional stylized engraving, in order to show the intaglio more clearly.

Being around 2000 years old, it has a heavily encrusted, natural, well aged patina

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading read more

395.00 GBP

Roman Ist Century AD Hippocampus Intaglio Engraved Bronze 'Status' Ring. Around 2000 Years Old. From The Time Of the Divine Augustus, The First Emperor of Rome

Henig type Xb bronze Roman ring around 1900 -2000 years old. In copper bronze with great, natural age patination

In the Iliad, Homer describes Poseidon, god of horses, earthquakes, and the sea, driving a chariot drawn by brazen-hoofed horses over the sea's surface, and Apollonius of Rhodes, describes the horse of Poseidon emerging from the sea and galloping across the Libyan sands.8 This compares to the specifically "two-hoofed" hippocampi of Gaius Valerius Flaccus in his Argonautica: "Orion when grasping his father’s reins heaves the sea with the snorting of his two-hooved horses." In Hellenistic and Roman imagery, however, Poseidon (or Roman Neptune) often drives a sea-chariot drawn by hippocampi. Thus, hippocampi sport with this god in both ancient depictions and much more modern ones, such as in the waters of the 18th-century Trevi Fountain in Rome surveyed by Neptune from his niche above.

The engraved intaglio seal ring was important for displaying the Roman's status. For example Tiberius, who was after all left-handed according to Suetonius, thus displays a ring in his bronze portrait as the Pontifex Maximus: The complete Roman Empire had around a 60 million population and a census more perfect than many parts of the world (to collect taxes, of course) but identification was still quite difficult and aggravated even more because there were a maximum of 17 men names and the women received the name of the family in feminine and a number (Prima for First, Secunda for Second…). A lot of people had the same exact name.

So the Roman proved the citizenship by inscribing themselves (or the slaves when they freed them) in the census, usually accompanied with two witnesses. Roman inscribed in the census were citizens and used an iron or bronze ring to prove it. With Augustus, those that could prove a wealth of more than 400,000 sesterces were part of a privileged class called Equites (knights) that came from the original nobles that could afford a horse. The Equites were middle-high class and wore a bronze or gold ring to prove it, with the famous Angusticlavia (a tunic with an expensive red-purple twin line). Senators (those with a wealth of more than 1,000,000 sesterces) also used the gold ring and the Laticlave, a broad band of purple in the tunic.

So the rings were very important to tell from a glimpse of eye if a traveller was a citizen, an equites or a senator, or legionary. People sealed and signed letters with the rings and its falsification could bring death.

The fugitive slaves didn’t have rings but iron collars with texts like “If found, return me to X” which also helped to recognise them. The domesticus slaves (the ones that lived in houses) didn’t wore the collar but sometimes were marked. A ring discovered 50 years ago is now believed to possibly be the ring of Pontius Pilate himself, and it was the same copper-bronze form ring as is this one.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading read more

395.00 GBP

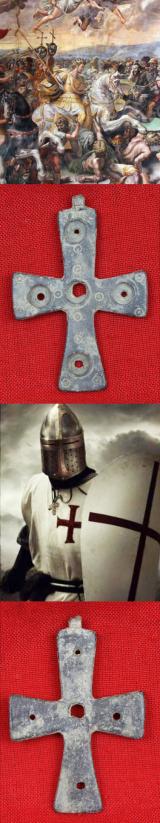

A Fabulous, Most Rare & Exceptionally Large, Imperial Roman Byzantine Empire, Original, Incised & Pierced Pectoral Stigmata Cross 4th Century, Used until 10th Century AD from Jerusalem. Used from the Time of Emperor Constantine to the Earliest Crusades.

In superb condition, it is exceptionally rare due to its large size, extraordinary large {yet wearable} size with beautiful patination, almost 3" long. The stigmata cross represents the five wounds of Christ. The incisions could be set cabochon gemstones such as ancient garnets.

The form of earliest Christian Cross Crucifix worn around the neck over the Roman toga to clearly show one’s position as, say, a Christian noble or tribune of status in the Eastern Roman Empire of Emperor Constantine, and it may have been worn by subsequent generations as a symbol of continuity and stability and devotion of the new faith of the Empire. Later, in the evolution of Christianity in the East, acquired by or presented to a Crusader Knight and worn upon his tabard as a symbol of his devotion to liberating Jerusalem.

One of our clients bought a fabulous good sized Crusades period bronze cross from us recently, and had a jeweller make a wearable gold mount and hanging ring so it could be worn once more almost 1000 years since it was originally worn to the Holy Land. Another client acquired an encolpion cross and had a bespoke good sized frame made for its display, both looked absolutely stunning.

Just over 1700 years ago, it was written, a cross of light bearing the inscription “in hoc signo vinces” (in this sign you will conquer) miraculously appeared to Roman Emperor Constantine before the battle of Milvian Bridge. The Battle of the Milvian Bridge took place between the Roman Emperors Constantine I and Maxentius on 28 October 312. His victory over his brother-in-law and co- emperor Maxentius and subsequent conversion to Christianity had a profound impact on the course of Western civilization.

Byzantine is the term commonly used since the 19th century to refer to the Greek-speaking Roman Empire of the Middle Ages centred in the capital city of Constantinople. During much of its history, it was known to many of its Western contemporaries as the Empire of the Greeks, due to the dominance of the Greek language and culture. However, it is important to remember that the Byzantines referred to themselves as simply as the Roman Empire. As the Byzantine era is a period largely fabricated by historians, there is no clear consensus on exactly when the Byzantine age begins; although many consider the reign of Emperor Constantine the Great, who moved the imperial capital to the glorious city of Byzantium, renamed Constantinople and nicknamed the “New Rome,” to be the beginning. Others consider the reign of Theodosius I (379- 395), when Christianity officially supplanted the pagan beliefs, to be the true beginning. And yet other scholars date the start of the Byzantine age to the era when division between the east and western halves of the empire became permanent.

While Christianity replaced the gods of antiquity, traditional Classical culture continued to flourish. Greek and Latin were the languages of the learned classes. Before Persian and Arab invasions devastated much of their eastern holdings, Byzantine territory extended as far as south as Egypt. After a period of iconoclastic uprising came to resolution in the 9th Century, a second flowering of Byzantine culture arose and lasted until Constantinople was temporarily seized by Crusaders from the west in the 13th Century. Christianity spread throughout the Slavic lands to the north. In 1453, Constantinople finally fell to the Ottoman Turks effectively ending the Byzantine Empire after more than 1,100 years. Regardless of when it began, the Byzantine Empire continued to carry the mantle of Greek and Roman Classical cultures throughout the Medieval era and into the early Renaissance, creating a golden age of Christian culture that today continues to endure in the rights and rituals of the Eastern Orthodox Church. Byzantine art and culture was the epitome of luxury, incorporating the finest elements from the artistic traditions of both the East and the West..

Many items of antiquity we acquire are from the era of the Grand Tour.

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land.

Hanging loop lacking. read more

3995.00 GBP

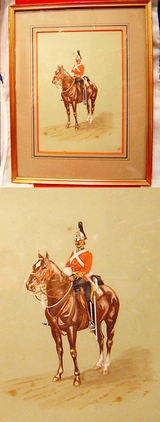

A Superb, Original Watercolour of a Victorian 1st Royal Dragoons NCO by H.R. Coombe

A most attractive portrait of a mounted Sergeant of Dragoons in full dress probably late Victorian. One of the non commissioned officers of one of the great historical regiments of the British Army. 14 x 19 framed picture 8.75 x 12.5 inches The regiment also fought at the Battle of Beaumont in April 1794 and the Battle of Willems in May 1794 during the Flanders Campaign. It served under Viscount Wellesley, as the rearguard during the retreat to the Lines of Torres Vedras in September 1810, and charged the enemy at the Battle of Fuentes de Onoro in May 1811 during the Peninsular War. The regiment also took part in the charge of the Union Brigade under the command of Major-General William Ponsonby at the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815 during the Hundred Days Campaign. Captain Alexander Kennedy Clark, an officer in the regiment, captured the French Imperial Eagle of the 105th Line Infantry Regiment during the battle.

In 1816 a detachment of the regiment was involved with suppressing the Littleport riots.

Rough Rider Robert Droash of the 1st Royal Dragoons after serving in the Crimean War in 1856

The regiment, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel John Yorke, also took part in the charge of the heavy brigade at the Battle of Balaclava in October 1854 during the Crimean War. Having been re-titled the 1st (Royal) Dragoons in 1877, the regiment also saw action at the Battle of Abu Klea in January 1885 during the Mahdist War. In January 1900, during the Second Boer War, the regiment was part of a force that set out to discover the western flank of the Boer lines. It was able to ambush a column of about 200 Boers near Acton Homes and successfully trapped about 40 of them. Following the end of the war, 623 officers and men of the regiment left South Africa on the SS Kildonan Castle, which arrived at Southampton in October 1902.

The regiment, which had been serving at Potchefstroom in South Africa when the First World War started, returned to the UK and than landed at Ostend as part of the 6th Cavalry Brigade in the 3rd Cavalry Division in October 1914 for service on the Western Front.[9] It took part in the First Battle of Ypres in October 1914, the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, the Battle of Loos in September 1915 and the advance to the Hindenburg Line in 1917 read more

475.00 GBP

A Simply Stunning Ancient Roman Museum Grade Fine Gold Seal Ring with Intaglio Portrait Engraved Garnet Gem Stone 2nd to 3rd Century A.D. Likely a Depiction of an Emperor Such As Hadrian, Marcus Aurelius, Lucius Verus, or Even A Parthian Vassal King.

A museum grade, around 1900 year old pure gold ancient Roman intaglio carved garnet gemstone seal ring.

Worn by such a noble as the rank of Imperial Legate { Legatus Augusti pro praetore}. The commander of two or more legions, who also served as the governor of an eastern province in which the legions he commanded were stationed. He was of Senatorial rank and was appointed by the Emperor for a term of 3 or 4 years.

The carved gem’s seal is depicting a profile hand carving, possibly of an Emperor such as Verus, or vassal King of Parthia. Possibly as a celebration of Verus’s ‘Triumph’ from the Parthian War. Classified by the seminal classification of ancient ring forms, by Dr. Martin Henig, as Ancient Roman, Henig type II

The Roman triumph was one of ancient Rome’s most important civic and sacred institutions. These spectacular processions were celebrations of Rome’s military victories, the courage of its soldiers, and the favour of the gods. They were also one of the highest honors a Roman man could achieve: designated a triumphator, he was awarded a grand procession through the imperial capital. The lavish parade of prisoners and captured treasures was sure to guarantee the eternal fame of the conquering general. Over time, the triumph became an important tool in the manipulation of Roman politics.

Made and worn by the highest ranking Roman, such as a Legate, possibly even a member of the Imperial household at the time from Emperors Marcus Aurelias, Lucius Verus, & Commodus, and just into the early following century.

Rings were one of the most popular pieces of jewellery in Roman culture. Under the Republic the wearing of gold rings was exclusively reserved to certain classes of persons or for specific occasions. In the late 3rd century BC only senators and knights equo publico had this privilege. Towards the end of the Republic, gold rings were also bestowed on civilians. Under the Roman Empire gold rings, although still regarded as a privilege and awarded as a military distinction

During the era of dual Emperors Marcus Aurelius, and Lucius Verus, 161 to 180 ad, the last part of his reign was dramatically represented in the blockbuster film 'Gladiator', starring Richard Harris as the Emperor Marcus Aurelias. He acceded to the throne of Emperor alongside his adoptive brother, who reigned under the name Lucius Verus. Under his rule the Roman Empire witnessed heavy military conflict. In the East, the Romans fought successfully with a revitalised Parthian Empire and the rebel Kingdom of Armenia. Marcus defeated the Marcomanni, Quadi, and Sarmatian Iazyges in the Marcomannic Wars; however, these and other Germanic peoples began to represent a troubling reality for the Empire. Ultimately, the Romans were victorious in the Parthian War of 161-167 CE. After the sacking of Ctesiphon and Seleucia, Lucius Verus took the title Parthicus Maximus. As a feature of his imperial titulature, the epithet conveyed his military might and power. But the question remains: to what extent can the Roman victory over the Parthian Empire be attributed to Verus?

Indeed, much of the successes the Romans enjoyed in this eastern war surely belong to the supremely able retinue of generals and administrators who were with Verus at the time. Regardless, upon his return from the campaign, Verus was awarded a triumph, the traditional celebration of Roman military conquest that had been used since the Republican era. This was to be the high point of Verus’ imperial story, however. In 169 CE, as he was journeying back from the Danubian frontier — where he had been fighting in the Marcomannic wars with Marcus Aurelius — Verus suddenly fell ill and died. It is highly probable, according to historians, that Verus was a victim of the pestilence that his soldiers had carried back to the empire with them from the Parthian War.

Commodus. the successor and son of Emperor Antoninus Pius,, was the Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 177 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. His reign is commonly thought of as marking the end of a golden period of peace in the history of the Roman Empire, known as the Pax Romana.

Commodus became the youngest emperor and consul up to that point, at the age of 16. Throughout his reign, Commodus entrusted the management of affairs to his palace chamberlain and praetorian prefects, named Saoterus, Perennis and Cleander.

Commodus's assassination in 192, by a wrestler in the bath, marked the end of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was succeeded by Pertinax, the first emperor in the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors.

Jewellery in the Roman Republic

The core ideologies of the Roman Republic, centred around moderation and restraint, meant that elaborate jewellery was relatively unpopular until the transformation to imperial rule. The law of the Twelve Tables in the 5th century BC, limited the amount of gold which might have been buried with the dead. The Lex Oppia, 3rd century BC, fixed at half of an ounce the amount of gold which a Roman lady might have worn. During the Roman Empire, however, jewellery became a public display of wealth and power for the elite.

Rings of the higher ranks were often embellished with intaglios, cameos and precious gemstones. Mythology and Roman history were used as a repertoire of decorative themes. Roman rings featuring carved gemstones, such as carnelian, garnet or chalcedony, were often engraved with the depiction of deities, allegories and zoomorphic creatures.

1 inch across, UK size H1/2, {measured on the round inside the oval} 9.6 grams, approx 22 carat gold 91.16% Gold, 6.66% silver, 1.93% copper, which is a typical consistency of ancient Roman gold determined by x-ray flourescence analysis with Oxford Instruments in 2017

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity. read more

8950.00 GBP

A Superb 'Tower of London' Made Front Line Regimental British Light Dragoon & Hussars Flintlock Pistol Circa 1802 Napoleonic Wars, Peninsular War and Waterloo Service use

Excellent walnut stock with original patina to all parts steel brass and walnut. All fine brass fittings and captive ramrod. In original flintlock, made byThe Tower of London Armoury. GR Crown Tower stamped lock plate. With numerous ordnance inspectors stamps throughout.

This is the pattern of pistol for use by British Light Dragoon & Hussars Cavalry regiments, and called the New Land Pattern, used initially from around 1802, during the Peninsular War, the War of 1812, and the Hundred Days War, culminating at Waterloo.

It is simply a superb Napoleonic wars original collector's item and good condition example. Certainly with usual signs of combat service use but with excellent natural age patina. Excellent perfect crisp action.

Introduced in the 1796 and in production by 1802, the New Land Pattern Cavalry Pistol provided one model of pistol for all of Britain's light cavalry and horse artillery. Another new element was its swivel all steel ramrod, which greatly improved the process of loading the pistol on horseback and ensuring no loss of ramrod due to miss-handling or dropping..

The regiments that used this very pistol under The Duke of Wellington's command were;

Hussars

7th (Queen's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) — white facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and white sash

15th (King's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) — red facings, silver lace and buttons, red and yellow sash

18th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons (Hussars) — white facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and white sash, grey dolmans

Light Dragoons

8th (King's Royal Irish) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — red facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and red belt, grey dolmans

9th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — red facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and yellow belt

10th (Prince of Wales's Own Royal) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — red facings, silver lace and buttons, red and yellow sash

11th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — buff facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and buff belt

12th (Prince of Wales's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — yellow facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and yellow belt

13th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — buff facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and buff belt

14th (Duchess of York's Own) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — orange facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and orange belts

16th (Queen's) Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — red facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and red belt

17th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — white facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and white belt

19th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — yellow facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and yellow belt

20th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — orange facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and orange belt

21st Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — pink facings (black from 1814), gold lace and buttons, blue and pink belt

22nd Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — pink facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and pink belt, grey dolmans

23rd Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — red facings (maybe yellow), silver lace and buttons, blue and red belt

24th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — grey facings, gold lace and buttons, blue and grey belt

25th Regiment of (Light) Dragoons — grey facings, silver lace and buttons, blue and grey belt, grey dolmans

The division between 'heavy' and light was very marked during Wellington's time: 'heavy' cavalry were huge men on big horses, 'light' cavalry were more agile troopers on smaller mounts who could harass as well as shock.

During the Napoleonic Wars, French cavalry was un-excelled. Later, as casualties and the passage of years took their toll, Napoleon found it difficult to maintain the same high standards of cavalry performance. At the same time, the British and their allies steadily improved on their cavalry, mainly by devoting more attention to its organization and training as well as by copying many of the French tactics, organization and methods. During the Peninsular War, Wellington paid little heed to the employment of cavalry in operations, using it mainly for covering retreats and chasing routed French forces. But by the time of Waterloo it was the English cavalry that smashed the final attack of Napoleon's Old Guard.

We show superb Napoleonic Light Dragoons illustration prints in the gallery by David Higham, that were gifted to us by a grateful client.

These can be bought at the link below, and they are extremely comfortably priced.

https://www.printsforartssake.com/products/7th-queens-own-british-regiment-of-light-dragoons-waterloo-1815.

This is a complimentary recommendation, for which we make no financial gain

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

A Superb, Original, Long Viking Spear Head 1000 to 1100 Years Old, In Superb Excavated Condition. A True Museum Piece

Overall in superb and well preserved condition. Only deeper pitting on the socket, and small impact damage to one outer edge of the diamond form blade. Remarkably the socket still has it remaining rivet for fixing to the wooden haft at the base on the inside. This almost certainly may be a traditional Viking pattern welded blade, in the traditional 'Wolf's Teeth' form, but the surface is too intact to tell, however its shape is very similar to the most famous recovered 'Wolf's Teeth' Viking spear head in Helsinki Museum see gallery. According to the older parts of the Gulating Law, dating back to before the year 900 AD covering Western Norway, a free man was required to own a sword or ax, spear and shield. It was said that Olaf Tryggvason, King of Norway from 995-1000 AD, could throw two spears at the same time. In chapter 55 of Laxdæla saga, Helgi had a spear with a blade one ell long (about 50cm, or 20in). He thrust the blade through Bolli's shield, and through Bolli. In chapter 8 of Króka-Refs saga, Refur made a spear for himself which could be used for cutting, thrusting, or hewing. Refur split Þorgils in two down to his shoulders with the spear. The spearheads were made of iron, and, like sword blades, were made using pattern welding techniques (described in the article on swords) during the early part of the Viking era . They could be decorated with inlays of precious metals or with scribed geometric patterns

After forming the head, the smith flattened and drew out material to form the socket . This material was formed around a mandrel and usually was welded to form a solid socket. In some cases, the overlapping portions were left unwelded. Spear heads were fixed to wooden shafts using a rivet. The sockets on the surviving spear heads suggest that the shafts were typically round, with a diameter of 2-3cm (about one inch).

However, there is little evidence that tells us the length of the shaft. The archaeological evidence is negligible, and the sagas are, for the most part, silent. Chapter 6 of Gísla saga tells of a spear so long-shafted that a man's outstretched arm could touch the rivet. The language used suggests that such a long shaft was uncommon.

Perhaps the best guess we can make is that the combined length of shaft and head of Viking age spears was 2 to 3m (7-10ft) long, although one can make arguments for the use of spears having both longer and shorter shafts. A strong, straight-grained wood such as ash was used. Many people think of the spear as a throwing weapon. One of the Norse myths tells the story of the first battle in the world, in which Oðin, the highest of the gods, threw a spear over the heads of the opposing combatants as a prelude to the fight. The sagas say that spears were also thrown in this manner when men, rather than gods, fought. At the battle at Geirvör described in chapter 44 of Eyrbyggja saga, the saga author says that Steinþórr threw a spear over the heads of Snorri goði and his men for good luck, according to the old custom. More commonly, the spear was used as a thrusting weapon. The sagas tell us thrusting was the most common attack in melees and one-on-one fighting, and this capability was used to advantage in mass battles. In a mass battle, men lined up, shoulder to shoulder, with shields overlapping. After all the preliminaries, which included rock throwing, name calling, the trading of insults, and shouting a war cry (æpa heróp), the two lines advanced towards each other. When the lines met, the battle was begun. Behind the wall of shields, each line was well protected. Once a line was broken, and one side could pass through the line of the other side, the battle broke down into armed melees between small groups of men.

Before either line broke, while the two lines were going at each other hammer and tongs, the spear offered some real advantages. A fighter in the second rank could use his spear to reach over the heads of his comrades in the first rank and attack the opposing line. Konungs skuggsjá (King’s Mirror), a 13th century Norwegian manual for men of the king, says that in the battle line, a spear is more effective than two swords. In regards to surviving iron artefacts of the past two millennia, if Western ancient edged weapons were either lost, discarded or buried in the ground, and if the ground soil were made up of the right chemical composition, then some may survive exceptionally well. As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity 13.5 inches long 350 grams weight. read more

1550.00 GBP