Antique Arms & Militaria

A Very Fine Ancient Roman Status Copper Bronze Ring Discovered Around 200 Years Ago Near Hadrian's Wall Circa 1820 Engraved With Pagan Sun Cross

2nd to 3rd Century a.d. From the time of the emperor's

Trajan (98–117 AD

Hadrian (117–138 AD

Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD

Marcus Aurelius (161–180 AD

Lucius Verus (161–169 AD

Commodus (177–192 AD

Overall in very nice wearable condition , and a good size. The Pagan sun cross engraving is worn but can be still seen for the most part.

The complete Roman Empire had around a 60 million population and a census more perfect than many parts of the world (to collect taxes, of course) but identification was still quite difficult and aggravated even more because there were a maximum of 17 men names and the women received the name of the family in feminine and a number (Prima for First, Secunda for Second…). A lot of people had the same exact name.

So the Roman proved the citizenship by inscribing themselves (or the slaves when they freed them) in the census, usually accompanied with two witnesses. Roman inscribed in the census were citizens and used an iron or bronze ring to prove it. With Augustus, those that could prove a wealth of more than 400,000 sesterces were part of a privileged class called Equites (knights) that came from the original nobles that could afford a horse. The Equites were middle-high class and wore a bronze or gold ring to prove it, with the famous Angusticlavia (a tunic with an expensive red-purple twin line). Senators (those with a wealth of more than 1,000,000 sesterces) also used the gold ring and the Laticlave, a broad band of purple in the tunic.

So the rings were very important to tell from a glimpse of eye if a traveler was a citizen, an equites or a senator, or legionary. People sealed and signed letters with the rings and its falsification could bring death.

The fugitive slaves didn’t have rings but iron collars with texts like “If found, return me to X” which also helped to recognize them. The domesticus slaves (the ones that lived in houses) didn’t wore the collar but sometimes were marked. A ring discovered 50 years ago is now believed to possibly be the ring of Pontius Pilate himself, and it was the same copper-bronze material

Like many of our selection of antiquities, many originally arrived in England as souvenirs of a Grand Tour, from around 200 years ago,

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land. read more

345.00 GBP

A Irish Rebellion Knights Rowel Spur of the 16th Century, With its Buckle

From the Desmond Rebellions, that occurred in 1569-1573 and 1579-1583 in the Irish province of Munster.

They were rebellions by the Earl of Desmond head of the FitzGerald dynasty in Munster and his followers, the Geraldines and their allies, against the threat of the extension of their South Welsh Tewdwr cousins of Elizabethan English government over the province. The rebellions were motivated primarily by the desire to maintain the independence of feudal lords from their monarch, but also had an element of religious antagonism between Catholic Geraldines and the Protestant English state. They culminated in the destruction of the Desmond dynasty and the plantation or colonisation of Munster with English Protestant settlers. 'Desmond' is the Anglicisation of the Irish Deasmumhain, meaning 'South Munster'. FitzMaurice first attacked the English colony at Kerrycurihy south of Cork city in June 1569, before attacking Cork itself and those native lords who refused to join the rebellion. FitzMaurice's force of 4,500 men went on to besiege Kilkenny, seat of the Earls of Ormonde, in July. In response, Sidney mobilised 600 English troops, who marched south from Dublin and another 400 landed by sea in Cork. Thomas Butler, Earl of Ormonde, returned from London, where he had been at court, brought the Butlers out of the rebellion and mobilised Gaelic Irish clans antagonistic to the Geraldines. Together, Ormonde, Sidney and Humphrey Gilbert, appointed as governor of Munster, devastated the lands of FitzMaurice's allies in a scorched earth policy. FitzMaurice's forces broke up, as individual lords had to retire to defend their own territories. Gilbert, a half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh, was the most notorious for terror tactics, killing civilians at random and setting up corridors of severed heads at the entrance to his camps. Sir Humphrey Gilbert (c. 1539 ? 9 September 1583) of Devon in England was a half-brother of Sir Walter Raleigh (they had the same mother, Catherine Champernowne), and cousin of Sir Richard Grenville. Adventurer, explorer, member of parliament, and soldier, he served during the reign of Queen Elizabeth and was a pioneer of the English colonial empire in North America and the Plantations of Ireland. In 1588, the English Lord President of Munster, Sir Warham St. Leger, sent a tract to the English Privy Council identifying the kings of Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht, and the feudal lordships which were then in existence. For the most part, the rights and prerogatives of the Irish kings whose territories lay outside the Pale were recognized and honoured by the (English) government in Dublin, which prudently saw that centralized rule of all Ireland was impossible. Largest, richest and most politically developed of the Gaelic Kingdoms of Ireland was Munster, which at its height comprised all of what are today the counties of Cork, Kerry and Waterford, as well as parts of Limerick and Tipperary. Recovered in Ireland over 150 years ago in Kilkenny at a supposedly known battle area. We have mounted on a red board for display. We show for illustration purposes a portrait of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, and 16th century period engraving prints of the rebellion and the aftermath, the fleet landing, the troops marshalling and the execution of the rebels. read more

475.00 GBP

A Superb Historical Political Collectable, an Autograph of Benjamin Disreali, Framed With Small Portrait Print.

One of the great political and historical characters of the 19th century. From his personal letter to a gentleman in South Audley St. in London. Signed Disraeli in ink. Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, PC, FRS (21 December 1804 ? 19 April 1881) was a British politician and writer, who twice served as Prime Minister. He played a central role in the creation of the modern Conservative Party, defining its policies and its broad outreach. Disraeli is remembered for his influential voice in world affairs, his political battles with the Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone, and his one-nation conservatism or "Tory democracy". He made the Conservatives the party most identified with the glory and power of the British Empire. He is the only British Prime Minister of Jewish birth.

Disraeli was born in London. His father left Judaism after a dispute at his synagogue; young Benjamin became an Anglican at the age of 12. After several unsuccessful attempts, Disraeli entered the House of Commons in 1837. In 1846 the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel split the party over his proposal to repeal the Corn Laws, which involved ending the tariff on imported grain. Disraeli clashed with Peel in the Commons. Disraeli became a major figure in the party. When Lord Derby, the party leader, thrice formed governments in the 1850s and 1860s, Disraeli served as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Leader of the House of Commons. He also forged a bitter rivalry with Gladstone of the Liberal Party.

Upon Derby's retirement in 1868, Disraeli became Prime Minister briefly before losing that year's election. He returned to opposition, before leading the party to a majority in the 1874 election. He maintained a close friendship with Queen Victoria, who in 1876 created him Earl of Beaconsfield. Disraeli's second term was dominated by the Eastern Question?the slow decay of the Ottoman Empire and the desire of other European powers, such as Russia, to gain at its expense. Disraeli arranged for the British to purchase a major interest in the Suez Canal Company (in Ottoman-controlled Egypt). In 1878, faced with Russian victories against the Ottomans, he worked at the Congress of Berlin to obtain peace in the Balkans at terms favourable to Britain and unfavourable to Russia, its longstanding enemy. This diplomatic victory over Russia established Disraeli as one of Europe's leading statesmen.

World events thereafter moved against the Conservatives. Controversial wars in Afghanistan and South Africa undermined his public support. He angered British farmers by refusing to reinstitute the Corn Laws in response to poor harvests and cheap imported grain. With Gladstone conducting a massive speaking campaign, his Liberals bested Disraeli's Conservatives in the 1880 election. In his final months, Disraeli led the Conservatives in opposition. He had throughout his career written novels, beginning in 1826, and he published his last completed novel, Endymion, shortly before he died at the age of 76. read more

300.00 GBP

A Most Fearsome & impressive Original Medieval Crusaders Battle Mace, 700 to 800 Years Old

A most impressive but fearsome early weapon from the 1200's to 1300's around 700 to 800 years old, and most probably German. On replacement 'display' haft. An incredible elaborate 'pineapple' form lobed head that would be extremely effective at achieving its aim. This is also the form of Mace that could also mounted on a short chain with a haft and then used as a flail mace or scorpian sting for that extra reach while used on horseback. Unlike a sword or haft mounted mace, it doesn't transfer vibrations from the impact to the wielder. This is a great advantage to a horseman, who can use his horse's speed to add momentum to and under-armed swing of the ball, but runs less of a risk of being unbalanced from his saddle. On a Flail it had the name of a Scorpion in England or France, or sometimes a Battle-Whip. It was also wryly known as a 'Holy Water Sprinkler'. King John The Ist of Bohemia used exactly such a weapon, as he was blind, and the act of 'Flailing the Mace' meant lack of site was no huge disadvantage in close combat. Although blind he was a valiant and the bravest of the Warrior Kings, who perished at the Battle of Crecy against the English in 1346. On the day he was slain he instructed his Knights [both friends and companions] to lead him to the very centre of battle, so he may strike at least one blow against his enemies. His Knights tied their horses to his, so the King would not be separated from them in the press, and they rode together into the thick of battle, where King John managed to strike not one but at least four noble blows. The following day of the battle, the horses and the fallen knights were found all about the body of their most noble King, all still tied to his steed.

It is difficult to block with a shield or parry with a weapon such as this on a chain because it can curve over and round impediments and still strike the target. It also provides defence whilst in motion. However the rigid haft does have the advantage as the flail needs space to swing and can easily endanger the wielder's comrades.

Controlling the flail is much more difficult than rigid weapons. Mounted on a replaced old haft. One photo in the gallery is from a 13th century Manuscript that shows knights in combat, and one at the rear is using a stylised and similar Mace [photo for information only and not included with mace]. The head is around the size of a tennis ball. In the gallery is a section of a 13th century illuminated manuscript, The Smithfield Decretals showing two man-sized rabbits killing a restrained man with a mace, known as a 'bizarre and vulgar' illustration. A mace is a blunt weapon, a type of club or virge that uses a heavy head on the end of a handle to deliver powerful blows. A mace typically consists of a strong, heavy, wooden or metal shaft, often reinforced with metal, featuring a head made of stone, copper, bronze, iron, or steel.

The head of a military mace can be shaped with flanges or knobs to allow greater penetration of plate armour. The length of maces can vary considerably. The maces of foot soldiers were usually quite short (two or three feet). The maces of cavalrymen were longer and thus better suited for blows delivered from horseback. Two-handed maces could be even larger. During the Middle Ages metal armour such as mail protected against the blows of edged weapons. Solid metal maces and war hammers proved able to inflict damage on well armoured knights, as the force of a blow from a mace is great enough to cause damage without penetrating the armour. Though iron became increasingly common, copper and bronze were also used, especially in iron-deficient areas. The Sami, for example, continued to use bronze for maces as a cheaper alternative to iron or steel swords.

One example of a mace capable of penetrating armour is the flanged mace. The flanges allow it to dent or penetrate thick armour. Flange maces did not become popular until after knobbed maces. Although there are some references to flanged maces (bardoukion) as early as the Byzantine Empire c. 900 it is commonly accepted that the flanged mace did not become popular in Europe until the 12th century, when it was concurrently developed in Russia and Mid-west Asia.

.It is popularly believed that maces were employed by the clergy in warfare to avoid shedding blood (sine effusione sanguinis). The evidence for this is sparse and appears to derive almost entirely from the depiction of Bishop Odo of Bayeux wielding a club-like mace at the Battle of Hastings in the Bayeux Tapestry, the idea being that he did so to avoid either shedding blood or bearing the arms of war. Iron head 2 inches x 2.25 inches across, length 21 inches read more

1350.00 GBP

A Most Interesting & Fine Original Antique Edwardian Bastinado or Whipping Cane

Very flexible bamboo cane with a London hallmarked silver top dated 1902. In superb 'whippy' condition. Flagellation was so common in England as punishment that caning, along with spanking and whipping, are called "the English vice".

Caning can also be done consensually as a part of personal 'amusement'

Foot whipping, falanga or bastinado is a method of inflicting pain and humiliation by administering a beating on the soles of a person's bare feet. Unlike most types of flogging, it is meant more to be painful than to cause actual injury to the victim. Blows are generally delivered with a light rod, knotted cord, or lash.

The receiving person is forced to be barefoot and soles of the feet are placed in an exposed position. The beating is typically performed with an object like a cane or switch. The strokes are usually aimed at the arches of the feet and repeated a certain number of times.

Bastinado is also referred to as foot (bottom) caning or sole caning, depending on the instrument in use. The German term is Bastonade, deriving from the Italian noun bastonata (stroke with the use of a stick). In former times it was also referred to as Sohlenstreich

The first clearly identified written documentation of bastinado in Europe dates to 1537, and in China to 960.2 References to bastinado have been hypothesised to also be found in the Bible (Prov. 22:15; Lev. 19:20; Deut. 22:18), suggesting use of the practice since antiquity

Foot whipping was used by Fascist Blackshirts against Freemasons critical of Benito Mussolini as early as 1923. It was reported that Russian prisoners of war were "bastinadoed' at Afion camp by their Turkish captors during World War I. However British prisoners escaped this treatment. Also, as used in days gone by at Eton, Harrow, & Rugby, and by Miss Doris Goodstripe, of 37 Railway Cuttings, East Cheam (apparently) read more

145.00 GBP

An 18th Century English Small Sword Circa 1760

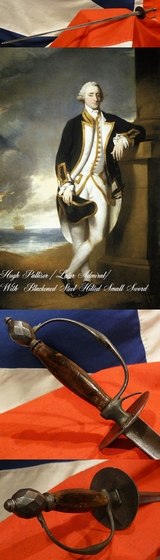

An English small sword often favoured by English naval officers, in blackened cut steel as this type of finish inhibited rust, single knuckle bow and an ovoid neo classical pommel with a fine diamond cut pattern. Plain wooden grip oval guard with small pas dan. Hollow trefoil blade with central fuller. Original blackened finish. One pas dans and the quillon have been shortened. See the standard work "Swords and Blades of the American Revolution" by George C. Neumann Published 1973. Sword 216s. Page 136 for two very similar swords. A particular painting showing a very good example of this is in the National Maritime Museum and it is most similar. The painting is of British Naval Captain Hugh Palliser, who wears the same form of sword with a blackened hilt , but with a gold sword knot which gave it a sleek overall appearance. A full-length portrait of Sir Hugh Palliser, Admiral of the White, turning slightly to the right in captain's uniform (over three years seniority), 1767-1774. He stands cross-legged, leaning on the plinth of a column, holding his hat in his right hand. The background includes a ship at sea. From 1764 to 1766, when he was a Captain, Palliser was Governor of Newfoundland, where James Cook, who had served under him earlier, was employed charting the coast. He was subsequently Comptroller of the Navy and then second-in-command to Augustus Keppel at the Battle of Ushant in 1778. Good condition overall, Blade 27.5 inches long read more

575.00 GBP

Rare, Victorian, British Board of Trade, Rocket Apparatus, Combination Gold Coin & Medal. 'Proof of Service at a Wreck'. This 19th Century Coin Medal Was A Value of 5/- For Rocket Launching Servicing A Wreck’ In Distress. {1/- Extra for Saving A Life}

Board of Trade, Life Saving Rocket Apparatus Service Gold Coin-Medal

Obverse: Port broadside view of a full-rigged ship at anchor. Legend: 'BOARD OF TRADE ROCKET APPARATUS'. Reverse: A large royal crown centre. 'PROOF OF SERVICE AT A WRECK'.

Interestingly, we had our first example in 20 years only a week or so ago, which we sold within just an hour or so, but one of our viewers saw our bronze example on our site and offered us this rarer still gold version which is the first we have seen in decades.

To attend a wreck at sea near a coast was very perilous indeed. Ships were only usually in such dire straights due to severe storms and the most foulest of weather. At such a time the crew of the rocket launching were at severe risk of death, that was almost as much as the ships crew. One had to remember the skill of swimming was not remotely as common as it is today, in fact most sailors purposely failed to learned to swim as a quick death by drowning was preferable to a long drawn out fate of swimming in a vast sea awaiting a most unlikely rescue.

The Board of Trade owned the apparatus which was held at Coastguard Stations. Users could claim expenses from the board. The rocket apparatus was used to fire a line to a ship in distress. The line then used to haul over hawsers and the block to be affixed to the mast. Once fixed a breeches buoy could be used, hauled on a continuous whip line, to take off passengers and crew one by one. It was used by Coastguards but also by Volunteer Life Brigades and Life Saving Companies. The first of these founded in Tynemouth in 1864. Coastguards trained the volunteers in the use of the rocket apparatus. This was a medal come coin that had a face value.

Afterwards all those who helped at a shipwreck were awarded one of these coin medals which they could redeem for cash if they so chose. The lesser version had a redemption value of 2/6 {two shillings and sixpence} For attending a wreck, or,.this superior type has a redemption value of 5/- {five shillings} For proof of rocket launching service at a wreck, but with an extra 1/- {one shilling} awarded for saving a life.

They came in three grades, as well as three classifications. There were gold, silver, and bronze grades apparently, although, not of course solid gold, just like the famous Olympic medals, but only in silver or gold finish, never solid gold.

the gold finish is excellent except one small section that has corrupted and now lost its gold surface {see the photos, in the 5,o'clock position on the sailing ship side}

Royal Mint (Tower Hill), London, United Kingdom. read more

145.00 GBP

Circa 600 ad Middle Ages Sword Blade, Re-Hilted Around 1000 Years Ago At The Time of the Norman Invasion in 1066 of a Norseman Of Viking Origin. It Is Around 1400 Years Old, Later Used Around 1000 Years Ago, And The Crusades To Liberate The Holy Land

It is very rare indeed to fine an original sword from the pre Norman period, but this one is exceptional, in that it is very likely mounted with an earlier inlaid blade of the 5th to 8th century, possibly a Norse or Frankish ancestor of its Norman conquest period owner, therefore its blade was already between 300 to 500 years old, when it was hilted around 900 to 1000 years ago during the Norman Conquest. Thus the blade could be between 1300 to 1500 years old. The Normans that invaded England, Britain’s last and final conquerors, were settled Vikings, that remained in Normandy after the Viking seiges of Paris era in the 800’s.

Scandinavia as the Origin:

The Vikings, and later the Normans, originated from Scandinavia, particularly the regions of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

Raids and Settlements:

In the 9th century, Scandinavian Vikings began raiding the northern and western coasts of France.

By about 900, after six sieges of Paris, they had established a permanent foothold in the valley of the lower Seine River, eventually leading to the creation of the County of Rouen and later the Duchy of Normandy.

The intermingling between the Norse Vikings and the native Franks led to the development of a distinct Norman identity, adopting the French language, religion, and social customs.

From Vikings to Normans:

Despite their eventual adoption of Christianity and French culture, the Normans retained many of their Viking traits, such as their adventurous spirit and martial skills.

The six sieges of Paris may well have created a lesson for the future that has rarely been learned by its victims. After every siege began the Viking raiders were simply paid to go away and loot another part of France, which meant it happened six times in around 40 years. The Vikings learnt quite quickly the concept and incredible advantages of the ‘Danegeld’, { so known as such, due to, “to pay the Dane to go away, meant he will forever return for more”}.

It was the earliest Norman knights that went on the earliest crusades to liberate Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Such as Richard the Lionheart, aka King Richard the 1st. The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated and supported by the Christian Latin Church in the medieval period, primarily aimed at reclaiming the Holy Land from Muslim control. These campaigns, spanning from 1095 to 1291, were driven by a mix of religious fervor, political ambitions, and economic opportunities

The blade is shorter than when first used, with the end probably damaged and lost in combat. It is inlaid with inserts of copper, bronze and silver, in a circular bullet shaped patterns, one with 3 metal concentric circles. The pommel appears to be once further inlaid with silver. All the indications are that this amazing sword could very likely have been used by a very high ranking nobleman in the Norman Invasion 1066 period, and it most likely it had already been used by a highborn warrior or noble for almost 5 centuries prior to its re-hitting during the time of the invasion of Britain.

This piece simply a remarkable artefact from the previous two millennia.

It is a joy to own it even just for a very brief and it is still a wonderful original knight’s sword from the days of the Norman invasion, and prior to that, from the period known to historians as the ‘dark ages‘

It is an iron two-edged sword with broad two-edged lentoid-section blade, slightly tapering square-section crossguard. flat tang, D-shaped pommel, likely with inlaid silver, vertical bar to each face; the blade has traces of copper inlay to one face, to the other two applied discs: the upper copper-alloy with punched rosette detailing, the lower abraded to its present state of three concentric rings (apparently copper, bronze and silver). 850 grams, 61cm (24"). Fair condition, typical for its great age; lower blade now absent; edges notched and partly absent, all potentially due to combat.

See Oakeshott, E., Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991, items X.4, X.5, and see p.21, item 8, for the blade.

The blade does not bear a fuller and is a plain lentoid-section which it is why it could well indicate a date of manufacture in the 5th-8th century, the Dark Ages in northern Europe; the crossguard and the pommel are the re-hilted later additions, more typical of the later 10th century, i.e. Petersen's Type X (Oakeshott, p.25). The Normans were an ethnic group that arose from contact between Norse Viking settlers of a region in France, named Normandy after them, and indigenous Franks and Gallo-Romans. The settlements in France followed a series of raids on the French coast mainly from Denmark — although some came from Norway and Iceland as well — and gained political legitimacy when the Viking leader Rollo agreed to swear fealty to King Charles III of West Francia following the Siege of Chartres in 911 AD. The intermingling of Norse settlers and native Franks and Gallo-Romans in Normandy produced an ethnic and cultural "Norman" identity in the first half of the 10th century, an identity which continued to evolve over the centuries. The new Norman rulers were culturally and ethnically distinct from the old French aristocracy, most of whom traced their lineage to the Franks of the Carolingian dynasty from the days of Charlemagne in the 9th century. Most Norman knights remained poor and land-hungry, and by the time of the expedition and invasion of England in 1066, Normandy had been exporting fighting horsemen for more than a generation. Many Normans of Italy, France and England eventually served as avid Crusaders soldiers under the Italo-Norman prince Bohemund I of Antioch and the Anglo-Norman king Richard the Lion-Heart, one of the more famous and illustrious Kings of England.The Story of the Norman Conquest

The majority of the scenes which together tell the story of the Norman Conquest match in many instances with medieval written accounts even if there are, as one might expect with a purely visual narrative, some omissions such as the Anglo-Saxons’ battle with Norway’s Harald Hardrada at Stamford Bridge three weeks prior to Hastings. Again because it is a visual account, with only a few Latin words as pointers, many scenes are open to several interpretations. The tapestry starts with a scene set in 1064 CE where the English king Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE) says farewell to Harold Godwinson, his brother-in-law and the Earl of Wessex, who is to travel to Normandy on an unknown mission. Norman writers would record the mission’s purpose as a pledge of Saxon loyalty to William, Duke of Normandy, while an English chronicle suggests it was merely a visit to secure the release of Saxon prisoners. On 14 October 1066, William’s forces clashed with an English army near Hastings. Within a century of these events taking place, over a dozen writers had described the battle and its aftermath. Some of these accounts are lengthy, but they contradict each other and do not allow us to reconstruct the battle with any certainty.

English perspectives on the Battle of Hastings are found in the Old English annals known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. In one version, perhaps copied in the 1070s, it was claimed that William built a ‘castel’ at Hastings before Harold arrived. Harold then gathered a large army but William attacked before Harold could organise his troops. There were heavy casualties on both sides: among the dead were King Harold himself and his brothers, Leofwine and Gyrth.There are also differing accounts of one of the most iconic yet debated parts of the battle: the death of Harold. Was he killed by an arrow to the eye, as claimed by Amatus of Monte Cassino, writing in the 11th century? Was he hacked to bits, as recounted by Bishop Guy of Amiens (died 1075)? Or was he shot with arrows and then put to the sword, as described by the 12th-century chronicler, Henry of Huntingdon? Hastings is one of the most famous battles in English history. Modern historians continue to debate its impact. The Norman Conquest brought many social, economic, political and cultural changes, but some people living in 11th-century England did not even consider this battle to be the most important event of 1066.

A monk writing at Christ Church, Canterbury, recorded just two events for that year in a chronicle kept at the cathedral: ‘Here King Edward died. In this year, Christ Church burned.’ Another scribe then added the words, ‘Here came William’. This is a good reminder that that the Battle of Hastings did not affect everyone in the same way, even if it became part of English folklore. This fabulous most ancient sword could be simply framed under glass for display. Almost every weapon that has survived today from this era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one, because only the swords of kings, that have been preserved in national or Royal collections are today still in a good state and condition. We will include for the new owner a complimentary wooden display stand, but this amazing ancient artefact of antiquity would also look spectacular mounted within a bespoke case frame, or, on a fine cabinet maker constructed display panel. read more

7995.00 GBP

Pair of Magnificent, French Royal Grade & Simply Superb Solid Silver Mounted 18th Century 'Parisian' Saddle & Duelling Pistols, Last Used in Combat At Waterloo, Bespoke Made by Maitre Kettinis, Arquebusier a Paris, Of Museum Quality

Just part of our stunning, original, Waterloo collection display.

This is truly magnificent pair of Museum grade, highest rank, officer's saddle cum duelling pistols, used by a family descendant of the original owner, who used them in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary era, and then by his descendant who served in the Napoleonic wars, Peninsular and Waterloo.

The pair of solid silver mounted long, saddle pistols with gold inlaid barrels, bespoke hand made by their Parisian master gunsmith, for their original, nobleman or prince, owner by Maitre Lambert Kettenis of Paris, and we have a photo of an original 18th century document from the office of the Directoire General des Archives, in France, with his name listed for probate in 1770. From the era and quality of royal grade pistols as the world famous Lafayette-Washington-Jackson pistols.

Wonderful carved walnut stocks with rococo flower embellishments solid silver furniture including long eared butt caps, sideplate chisselled with stands of arms, chisselled silver mounted trigger guards hallmarked and barrel ramrod pipes, all sublimely engraved and chiselled with wonderful detailing of florid designs, and stands of arms, fine steel locks, with flintlock later adapted percussion actions, engraved with the name of Maitre L Kettenis.

Very similar to the French Lafayette-Washington pistols made in circa 1775. While of great historical importance, those pistols were also very fine pieces indeed, just like ours, but they had less expensive steel mounts, whereas these are solid silver, but both are typical of the finest gunsmith workmanship of the day. The Washington pistols were purchased by the Marquis de Lafayette, and were presented by him, to General George Washington, during the Revolutionary War in 1778. They, just as these pistols, are finest examples of eighteenth-century sidearms with exquisite carved and engraved Rococo embellishments. The Washington Lafayette pair are likely the best documented pistols of their kind once belonging to Washington. The Washington pair sold in 2002 for just under $2,000,000.00. King George III, acquired another pair of pistols most similar to these and Washingtons, and they are the collection of the Royal Family of England at Windsor Castle. George III ascended the throne in 1760. As with all our antique guns, no license is required as they are all unrestricted antique collectables

These pair of pistols must’ve been handmade for an prince or nobleman of highest status and rank, such as colonel or general, at the time of the Anglo French wars in America in the 1760s and likely used continually through the American Revolutionary War period and into the Napoleonic era. After which they were ‘convert silex’ from flintlock, in order to enhance their performance in poor and wet weather. A system much promoted by Napoleon himself, in fact he made entreaties to the Reverend Forsyth of Scotland, a well known earliest designer of the silex system, to become Napoleon’s consultant to his armoury in Versailles, an offer which Forsyth refused due his loyalty to the British crown.

Flintlocks could not function in damp or rainy conditions, but the system silex surmounted this problem, and enabled such converted pistols for their more effective and efficient use for at least for a further 20 years.

Picture in the gallery is of a surviving register in a French National archive of the official record of the will of Kettenis, Lambert, Maître arquebusier, it further names his wife, as femme Louise Elisabeth. His will was probated 1770-07-10.

This stunning pair are in superb condition for age, and we have left them just ‘as-is’, only one hammer cocks and locks perfectly, yet both actions have superbly crisp and strong main springs, with one small nipple top a/f.. read more

9950.00 GBP

A Fabulous Circa 1808, A Year XII Silex Pistol for General Staff Officers, Octagonal Rifled Barrel in 17 mm calibre, Napoleonic Period Pistol By Napoleon’s Personal Gunsmith,The Great Jean Le Page of Paris

A Napoleonic pistol made by one of the greatest and collectable makers of France. Chequered grip, octagonal butt cap, octagonal barrel heavy scroll engraved with Le Page of Paris, flared muzzle octagonal barrel with multi groove rifling. Converse silex action, to enable ignition in foul weather.

The first modern use of a General Staff was in the French Revolutionary Wars, when General Louis-Alexandre Berthier (later Marshal) was assigned as Chief of Staff to the Army of Italy in 1795. Berthier was able to establish a well-organised staff support team. Napoleon took over the army the following year and quickly came to appreciate Berthier's system, adopting it for his own headquarters, although Napoleon's usage was limited to his own command group.

The Staff of the Grande Armée was known as the Imperial Headquarters and was divided into two major sections: Napoleon's Military Household and the Army General Headquarters. A third department dependent on the Imperial Headquarters was the office of the Intendant Général (Quartermaster General), providing the administrative staff of the army.

Made and used by a staff officer, from the period of Napoleon’s Grand Armee. The Grand Armee was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empire to exercise unprecedented control over most of Europe. Widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest fighting forces ever assembled, however, it suffered enormous losses during the disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812, after which it never recovered its strategic superiority.

The Grande Armée was formed in 1804 from the L'Armée des côtes de l'Océan (Army of the Ocean Coasts), a force of over 100,000 men that Napoleon had assembled for the proposed invasion of Britain. Napoleon later deployed the army in Central Europe to eliminate the combined threat of Austria and Russia, which were part of the Third Coalition formed against France. Thereafter, the Grande Armée was the principal military force deployed in the campaigns of 1806/7, the French invasion of Spain, and 1809, where it earned its prestige, and in the conflicts of 1812, 1813–14, and 1815. In practice, however, the term Grande Armée is used in English to refer to all the multinational forces gathered by Napoleon in his campaigns.

Upon its formation, the Grande Armée consisted of six corps under the command of Napoleon's marshals and senior generals. When the Austrian and Russian armies began preparations to invade France in late 1805, the Grande Armée was quickly ordered across the Rhine into southern Germany, leading to Napoleon's victories at Ulm and Austerlitz. The French Army grew as Napoleon seized power across Europe, recruiting troops from occupied and allied nations; it reached its peak of one million men at the start of the Russian campaign in 1812,3 with the Grande Armée reaching its height of 413,000 French soldiers and over 600,000 men overall when including foreign recruits.4

In summer of 1812, the Grande Armée marched slowly east, and the Russians fell back with its approach. After the capture of Smolensk and victory at Borodino, the French reached Moscow on 14 September 1812. However, the army was already drastically reduced by skirmishes with the Russians, disease (principally typhus), desertion, heat, exhaustion, and long communication lines. The army spent a month in Moscow but was ultimately forced to march back westward. Cold, starvation, and disease, as well as constant harassment by Cossacks and Russian partisans, resulted in the Grande Armée's utter destruction as a fighting force. Only 120,000 men survived to leave Russia (excluding early deserters); of these, 50,000 were Austrians, Prussians, and other Germans, 20,000 were Poles, and just 35,000 were French.5 As many as 380,000 died in the campaign.6

Napoleon led a new army during the campaign in Germany in 1813, the defence of France in 1814, and the Waterloo campaign in 1815, but the Grande Armée would never regain its height of June 1812. In total, from 1805 to 1813, over 2.1 million Frenchmen were conscripted into the French Imperial Army

Jean Le Page continued the success of his predecessors as gunsmith to the House of Orleans, King Louis XVI, of the First Consul Bonaparte and then Emperor Napoleon I and King Louis XVIII. The factory is famous for its pistols, guns, luxury white arms and page swords during the First French Empire. During this era, many technical innovations were made such as over oxygenated powder in 1810, a water resistant gun in 1817, and invented the fulminate percussion system for firearms which replaced the flintlock.

Jean Le Page cemented the company’s reputation and position in history. As a gunsmith he is mentioned in numerous pieces of literature, and the firearms produced during this period are those most sought after and displayed in museums and the like, particularly due to their often famous provenance.

As a purveyor of arms to kings he brought in an extremely prestigious clientele and this includes Armand Augustin Louis de Caulaincourt, Duke of Vincence, baron Gaspard Gourgaud, the Marshall Emmanuel de Grouchy, General Charles de Flahaut, the Marchioness Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon, the Marshall André Masséna, Duke of Rivoli, Baron Daru, General Carlo Andrea Pozzo di Borgo, and the perfumier Jean-François Houbigant, among others.

Many pieces bear testimony to this sumptuous period, Jean Le Page "is, without doubt, the imperial gunsmith most quoted both in literary texts and in arms notices exhibited in museums". A shooting gun for Louis Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (future Philippe Égalité) is presented to the Museum of the Porte de Hal in Brussels. First Consul Bonaparte's sword is exhibited at the Château de Malmaison. The Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris also has several beautiful Le Page pieces including two of Emperor Napoleon I's shooting guns belonging to a series made in 1775 for King Louis XVI and modified around 1806 ; a silex gun that had belonged to King Louis XVIII and a nécessaire box containing a pair of silex guns for children, a gift from King Charles X to the Duke of Bordeaux, future Count of Chambord

The pistol has had an old contemporary thin crack repair at the buttstock, replaced rammer read more

1675.00 GBP