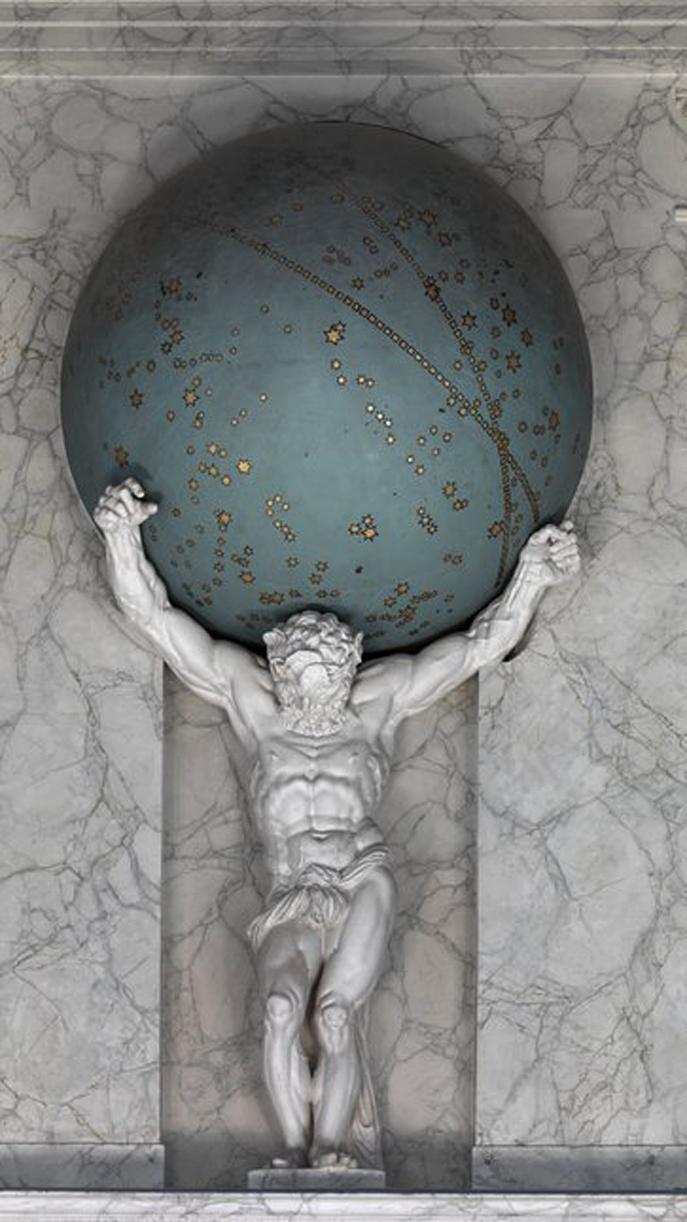

A Mid 19th Century, Crystal Witch Ball Scrying Glass On A Fabulous, Bronze Figure of the Ancient Greek Titan, Atlas Bearing The Armillary Celestial Sphere. A Most Intriguing Classic Antique Collector's Item Of The Esoteric Mystical Arts and Occultism

A simply fabulous original antique collectors item, probably Italian, from a Grand Tour, is of a bronze ‘after the antique’ statue of the Titan, Atlas bearing the heavens, set upon a polished wood pediment. A stunning piece that would look absolutely wonderful upon a desk or set upon a mantle. The crystal skrying ball is removed by simply lifting it from its armillary. An armillary is a spherical framework mounted atop a figure or stand, with which a sphere could be held or mounted within. If a metal sphere was within it, it could be plain, or engraved, with stars or celestial bodies { see a Grand Tour variant version in the gallery}

The crystal ball was used by gazing into their centre, for the divination of the future, and the answering of questions. As well as the warding off of evil spirits and misfortune. A fascinating treasure - of great artistic quality. Antique bronze sculpture of Atlas, set with a Louis XVI style armillary sphere

War and punishment of the Titanomachy

Atlas and his brother Menoetius sided with the Titans in their war against the Olympians, the Titanomachy. When the Titans were defeated, many of them (including Menoetius) were confined to Tartarus, but Zeus condemned Atlas to stand at the western edge of the earth and hold up the sky on his shoulders. Thus, he was Atlas Telamon, "enduring Atlas", and became a doublet of Coeus, the embodiment of the celestial axis around which the heavens revolve.

A common misconception today is that Atlas was forced to hold the Earth on his shoulders, but Classical art shows Atlas holding the celestial spheres, not the terrestrial globe;

Witch balls were found in England in the 1600 and 1700s originally to ward off evil spirits and spells. By the 1800s witch balls crossed the Atlantic to New England. They also spread to other parts of Europe, being found in Italy, France, and Constantinople. The witch ball originated among cultures where harmful magic and those who practiced it were feared. They are one of many folk practices involving objects for protecting the household. The word witch ball may be a corruption of watch ball because it was used to ward off, guard against, evil spirits. They may be hung in an eastern window, placed on top of a vase, or for the very wealthy set upon a decorative gold stand, either pedestal, or figural, or suspended by a cord (as from the mantelpiece or rafters). They may also be placed on sticks in windows or hung in rooms where inhabitants wanted to ward off evil.

Superstitious European sailors valued the talismanic powers of the witch balls in protecting their homes. Witch balls appeared in America in the 19th century and larger, more opaque variations are often found in gardens under the name gazing ball. This name derives from their being used for divination and scrying where a person gazes into them dreamily to try to see future events or to see the answers to questions. However, gazing balls contain no strands within their interior. The witch ball holds great superstition with regard to warding off evil spirits in our particular English counties of East Sussex and West Sussex. The tradition was also taken to overseas British colonies, such as the former British colonies of New England, and remains popular in coastal regions. Apparently, our Hawkins forebears ship’s that sailed across to the New World in the 1600’s, for both trade, emigres, and pilgrims, would carry at least one witch ball hung within a net on board. Our paternal grandmother hung one such in a net from her home’s East window all her life until her death in the 1980’s.

The history of the crystal ball as a device can be traced as far back as to the Medieval Period in central Europe (between 500 – 1500 AD) and in Scandinavia (1050 – 1500 AD). The very ancient art of using reflective surfaces in divination is called scrying and is almost as old as man himself. Queen Elizabeth I consulted Dr John Dee, philosopher, mathematician and alchemist for advice in government and a smoky quartz ball that belonged to Dee is now in the British Museum. Any antique crystal spheres are very desirable especially if a well-known reader has used them. This is the best one we have ever seen quite simply and it must have belonged to someone who took their craft incredibly seriously as it would have been tremendously expensive to make at the time.

Occultism, a group of esoteric religious traditions emerging primarily from 19th-century Europe. In particular, the term occultism is associated with the ideas of the French Kabbalist and ceremonial magician Éliphas Lévi as well as the various figures, both in France and abroad, who were strongly influenced by his writings. In the academic study of esotericism, the term is often used in a broader sense to characterize all esoteric traditions that have adapted to an increasingly secular, globalized, and scientific world, including Spiritualism, Spiritism, Wicca, and the New Age milieu.

History

The term occultism derives from occult, itself adopted from the Latin word occultus, meaning “hidden” or “secret.” In medieval and early modern Europe this term had been used in reference to “occult properties,” or forces that, even if invisible to the human eye, were believed to exist within material objects. In the 16th century the term occult gained additional meanings, coming to also describe specific traditions of thought, usually called “occult sciences” or “occult philosophies.” Among the traditions repeatedly labeled under these terms were alchemy, astrology, and magia naturalis (“natural magic”), all of which are now typically regarded as forms of esotericism.

The earliest known use of the term occultism comes from French, where l’occultisme appears in Jean-Baptiste Richard’s 1842 work Enrichissement de la langue française (“Enrichment of the French Language”). The word’s popularization nevertheless results largely from its use by Alphonse Louis Constant, a French author who published a series of books under the pseudonym Éliphas Lévi in the 1850s and ’60s. Sometimes referred to as the “founder of occultism,” Lévi was a committed Roman Catholic and socialist interested in many older esoteric traditions, including ceremonial magic, Kabbalah, and the use of the tarot. In his writings, most notably his highly influential Dogme et rituel de la haute magie (The Doctrine and Ritual of High Magic; 1854–1856), he wrote about a purported ancient and universal tradition of spiritual wisdom, the knowledge of which could help bridge the modern divide between science and religion. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many of the influential French figures who were inspired by Lévi—including Stanislas de Guaita, Joséphin Péladan, and Papus—also went on to describe their beliefs and practices as occultisme.

Scrying, also referred to as "seeing" or "peeping," is a practice rooted in divination and fortune-telling. It involves gazing into a medium, hoping to receive significant messages or visions that could offer personal guidance, prophecy, revelation, or inspiration

Scrying has been practiced in many cultures in the belief that it can reveal the past, present, or future. Some practitioners assert that visions that come when one stares into the media are from the subconscious or imagination, while others say that they come from gods, spirits, devils, or the psychic mind, depending on the culture and practice. There is neither any systematic body of empirical support for any such views in general however, nor for their respective rival merits; individual preferences in such matters are arbitrary

Undoubtedly, Nostradamus is the most recognized of scryers. In the sixteenth century, in ancient France, he was an astrologer and physician. He wrote in poetic quatrains which referenced future events. In his day, working as a magician conflicted with the law. His predictions were veiled to allow him to fly under the radar in that sense.

The Crystal Ball is a painting by John William Waterhouse completed in 1902. Waterhouse displayed both it and The Missal in the Royal Academy of 1902. The painting shows the influence of the Italian Renaissance with vertical and horizontal lines, along with circles "rather than the pointed arches of the Gothic".

Another painting in the gallery. Part of a private collection, the painting, by Pieter Claesz circa 1628, Still Life with Crystal Ball which depicts a crystal ball, a wand, a book of ceremonial magic, and a woman "weaving a spell", has been restored to show the skull which had been covered by a previous owner.

Yet another painting is Leonardo da Vinci's 'Salvator Mundi' Circa 1500, of Jesus Christ bearing a crystal ball in his left hand.

Another photo in the gallery is an extremely similar study, a 17th century patinated bronze version of the same study, after the antique, yet bearing within an armillary a bronze sphere. That slightly older and taller variant version was recently valued at around 8,000 gbp.

Overall the the crystal ball is very good indeed but just the odd near invisible age marking. 25.5 cm high

Code: 25501

1495.00 GBP