A Very Good, Rare, 18th Century American Revolutionary & Colonial Period Musket

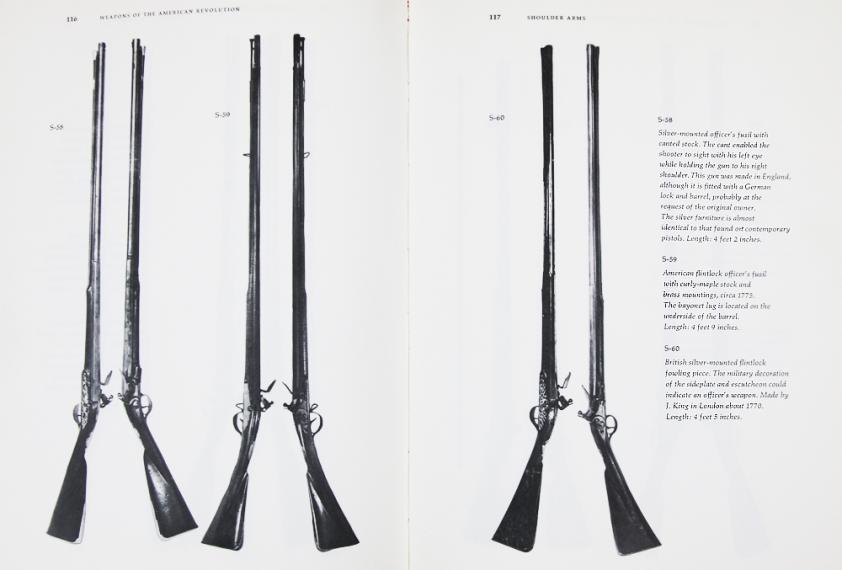

Long 47 inch two stage barrel, fine walnut stock with early down turned butt style. Stepped lock. Very crisp action. In the Metropolitan Museum in New York there are several extremely similar muskets used in the Revolutionary War just like it. See pages 116/117 Weapons of the American Revolution by Warren Moore, published in New York 1967 see photo 10 in the gallery . It is very similar to the early American Committee of Safety style Long Land Pattern musket. As the American Revolutionary War unfolded in North America, there were two principal campaign theaters within the thirteen states, and a smaller but strategically important one west of the Appalachian Mountains to the Mississippi River and north to the Great Lakes. The full-on military campaigning began in the states north of Maryland, and fighting was most frequent and severest there between 1775 and 1778. Patriots achieved several strategic victories in the South, the British lost their first army at Saratoga, and the French entered the war as an American ally.

In the expanded Northern theatre and wintering at Valley Forge, General Washington observed British operations coming out of New York at the 1778 Battle of Monmouth. He then closed off British initiatives by a series of raids that contained the British army in New York City. The same year, Spanish-supplied Virginia Colonel George Rogers Clark joined by Francophone settlers and their Indian allies conquered Western Quebec, the US Northwest Territory.

Starting in 1779, the British initiated a southern strategy to begin at Savannah, gather Loyalist support, and reoccupy Patriot-controlled territory north to Chesapeake Bay. Initially the British were successful, and the Americans lost an entire army at the Siege of Charleston, which caused a severe setback for Patriots in the region. But then British maneuvering north led to a combined American and French force cornering a second British army at Battle of Yorktown, and their surrender effectively ended the Revolutionary War. The American armies were small by European standards of the era, largely attributable to limitations such as lack of powder and other logistics. At the beginning of 1776, Washington commanded 20,000 men, with two-thirds enlisted in the Continental Army and the other third in the various state militias. About 250,000 men served as regulars or as militia for the Revolutionary cause over eight years during wartime, but there were never more than 90,000 men under arms at one time.

As a whole, American officers never equaled their opponents in tactics and maneuvers, and they lost most of the pitched battles. The great successes at Boston (1776), Saratoga (1777), and Yorktown (1781) were won from trapping the British far from base with a greater number of troops. Nevertheless, after 1778, Washington's army was transformed into a more disciplined and effective force, mostly by Baron von Steuben's training. Immediately after the Army emerged from Valley Forge, it proved its ability to match the British troops in action at the Battle of Monmouth, including a black Rhode Island regiment fending off a British bayonet attack then counter-charging for the first time in Washington's army. Here Washington came to realize that saving entire towns was not necessary, but preserving his army and keeping the revolutionary spirit alive was more important in the long run. Washington informed Henry Laurens "that the possession of our towns, while we have an army in the field, will avail them little."

Although Congress was responsible for the war effort and provided supplies to the troops, Washington took it upon himself to pressure the Congress and state legislatures to provide the essentials of war; there was never nearly enough. Congress evolved in its committee oversight and established the Board of War, which included members of the military. Because the Board of War was also a committee ensnared with its own internal procedures, Congress also created the post of Secretary of War, and appointed Major General Benjamin Lincoln in February 1781 to the position. Washington worked closely with Lincoln to coordinate civilian and military authorities and took charge of training and supplying the army. Most similar to the fusil de chasse/fusil du traite du plaine of 1740. Old forend repair. 63.25 inches long overall

Code: 23439

5750.00 GBP