Superb 18th Century American Revolutionary War, King George IIIrd Period Naval Hand Cannon From The Barbary Pirate Raids Period. From 1795, The Annual 'Tribute' Paid to the Regency of Algiers Was 20% of United States Federal Government Expenditure

Which translates today to the equivalent of one thousand two hundred billion dollars {$1.2 trillion} a year, in so called 'tribute' {ie, blackmail} payments to the Barbary States.

With traditional bell mouth, two barrel bands and large cascobel, without trunions, 18cm barrel.

Rare unmarked naval hand cannon of the type used off the Barbary Coast during the Age of Sail. Measures from raised muzzle to cascabel. Three stage body with round breech. Breech with lined border. Raised cannon muzzle. The iron is relatively smooth, with a good natural age patina throughout with areas of oxidation. A light shines through touchhole well. it could of double as a naval salute & powder tester.

From bases on the Barbary Coast, North Africa, the Barbary corsairs raided ships travelling through the Mediterranean and along the northern and western coasts of Africa, plundering their cargo and enslaving the people they captured. From at least 1500, the corsairs also conducted raids along seaside towns of Italy, France, Spain, Portugal, England and as far away as Iceland, capturing men, women and children. On some occasions, settlements such as Baltimore, Ireland were abandoned following the raid, only being resettled many years later. Between 1609 and 1616, England alone had 466 merchant ships lost to Barbary corsairs

Until the American Declaration of Independence in 1776, British treaties with the North African states protected American ships from the Barbary corsairs. During the American Revolutionary War, the Corsairs attacked American merchant vessels in the Mediterranean. However, on December 20, 1777, Sultan Mohammed III of Morocco issued a declaration recognizing America as an independent country, and stating that American merchant ships could enjoy safe passage into the Mediterranean and along the coast. The relations were formalized with the Moroccan–American Treaty of Friendship signed in 1786, which stands as the U.S.'s oldest non-broken friendship treaty with a foreign power.

The Barbary threat led directly to the United States founding the United States Navy in March 1794. While the United States did secure peace treaties with the Barbary states, it was obliged to pay tribute for protection from attack. The burden was substantial: from 1795, the annual tribute paid to the Regency of Algiers amounted to 20% of United States federal government's annual expenditures.

In 1798, an islet near Sardinia was attacked by the Tunisians, and more than 900 inhabitants were taken away as slaves. read more

A Good Silver Parachute Regiment Officer's Cap Badge 3rd Battalion Parachute Regt. Suez Campaign. Operations Telescope & Musketeer. A Franco-British Victory, Confounded by a Political Blunder

Circa 1953. Superb quality and condition with traditional officer's split-pin twin mounting loops.

Operation Telescope was a Franco-British operation conducted from 5 to 6 November 1956 during the Suez Crisis, consisting of a series of parachute drops launched by the British Parachute Brigade, in combination with French paratroop forces, 24 hours before the seaborne landing on Port Said during Operation Musketeer. Troops dropped onto Gamil airfield and Port Fuad to secure airfields and prevent Egyptian forces from providing air defence. It was put forward by the deputy Land Task Force Commander General André Beaufre under the original name Omelette which included many more drops but was adapted due to British fear of another failure like Arnhem and a lack of aircraft able to deploy paratroopers.

The capture of the airfield at El Gamil and the surrounding area was an essential element in Operation Musketeer, the joint Anglo-French airborne and amphibious assault on Port Said, with the ultimate aim of gaining control of the Suez Canal. The French 2nd Colonial Parachute Regiment were to land at Er Raswa while the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment, part of 16th Independent Parachute Brigade, were tasked with the attack on El Gamil, which would be the first British battalion parachute assault since World War II and the last to date. At the insistence of French commanders, the airborne assaults on El Gamil and Raswa were to take place a full 24 hours before the arrival of the seaborne element, in order to preserve the element of surprise, as it would be difficult to conceal the approach of the large invasion fleet.

Before the landing, the British launched airstrikes on Egyptian defensive positions around the battlefield, effectively neutralizing many of them. Still, as 3. PARA landed at 0515 GMT, they came under fire, unable to return it until they had retrieved the caches with their weapons. Egyptian fire was inaccurate however, and ultimately the British suffered very few casualties.

At 0515 GMT on 5th November 3 PARA conducted the first and last battalion sized operational parachute assault since the Second World War. Despite vigorous defensive fire El Gamil airfield was captured in 30 minutes. Vicious close-quarter fighting developed as the paratroopers continued the advance through a sewage farm and cemetery nearby, rolling up Egyptian coastal defences. Covering fire was provided to support the amphibious landings that arrived the next day and a successful link-up with 45 Commando achieved.

The British lacked heavy support equipment, but the small arms and light AT and support weapons they had were more than adequate to take the airfield, the AT being particularly effective at knocking out four concrete pillboxes. Other than these bunkers, the Egyptians withdrew to favourable terrain to avoid annihilation at the hands of the superior British forces. The Egyptians' three SU-100 self-propelled guns proved to be particularly difficult for the PARAs.

3. PARA then moved onto Port Said, surviving a friendly fire incident with French planes who strafed them. B Company captured the sewage works which provided cover from Egyptian snipers, however, not wanting to push forward and storm the highly defensible Coast Guard Barracks, they called in air support in the form of Wyverns who dropped bombs on the position for the loss of one aircraft and inflicting heavy casualties. Running out of ammo however, the British retreated to the sewage works.

16 km to the southeast, the French 2. RPC achieved a lot more success, managing to take the Western span of the Rawsa Bridges (rendered inoperable by damage) and the Said waterworks, cutting off the supplies into the city. With supplies cut off and a potential chokepoint captured by mid-morning, the French had achieved all their objectives on the first day.

Following the unsuccessful negotiation of a ceasefire during the night, C Company was sent to capture the cemetery at 0510 GMT, which was completed without opposition. This was followed up by an assault on the Coast Guard building from which a considerable amount of sniper fire was coming. The building was captured by 0800 with no casualties whereupon they were ordered to capture a hospital to complete the link up with 45 Commando.

In the closing stage of the battle, a patrol of four men was ambushed and injured by Egyptian fire whereupon a medical officer, Captain Elliot rescued them under heavy fire for which he was awarded the Military Cross.

‘Our quarrel is not with Egypt, still less with the Arab world. It is with Colonel Nasser. He has shown that he is not a man who can be trusted to keep an agreement. Now he has torn up all his country's promises to the Suez Canal Company and has even gone back on his own statements. ‘We cannot agree that an act of plunder which threatens the livelihood of many nations should be allowed to succeed. And we must make sure that the life of the great trading nations of the world cannot in the future be strangled at any moment by some interruption to the free passage of the canal.’

PRIME MINISTER SIR ANTHONY EDEN — 8 AUGUST 1956

Not hallmarked. read more

140.00 GBP

An Original & Beautiful Ancient & Archaic Warrior's Dagger of the Trojan Wars Era. A Bronze Long Dagger Circa 1200 bc Around 3200 Years Old, in Superb Condition With All Its Original Age Patination Intact

This is a most handsome ancient bronze long dagger from one of the most fascinating eras in ancient world history, the era of the so called Trojan Wars. A most similar dagger, but with its gold hilt panel intact, made from 1000 to1350bc, is on display in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, a gift of The Ahmanson Foundation. We show their dagger and its hilt with gold inlay, as the last two photos in the gallery.

The ancient Greeks believed the Trojan War was a historical event that had taken place in the 13th or 12th century BC, and believed that Troy was located in modern day Turkey near the Dardanelles. In Greek mythology, the Trojan War was waged against the city of Troy by the Achaeans (Greeks) after Paris of Troy took Helen from her husband Menelaus, the king of Sparta.

The war is among the most important events in Greek mythology and was narrated in many works of Greek literature, including Homer's Iliad and the Odyssey . "The Iliad" relates a part of the last year of the siege of Troy, while the Odyssey describes the journey home of Odysseus, one of the Achaean leaders. Other parts of the war were told in a cycle of epic poems, which has only survived in fragments. Episodes from the war provided material for Greek tragedy and other works of Greek literature, and for Roman poets such as Virgil and Ovid.

The war originated from a quarrel between the goddesses Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite, after Eris, the goddess of strife and discord, gave them a golden apple, sometimes known as the Apple of Discord, marked "for the fairest". Zeus sent the goddesses to Paris, who judged that Aphrodite, as the "fairest", should receive the apple. In exchange, Aphrodite made Helen, the most beautiful of all women and wife of Menelaus, fall in love with Paris, who took her to Troy. Agamemnon, king of Mycenae and the brother of Helen's husband Menelaus, led an expedition of Achaean troops to Troy and besieged the city for ten years due to Paris' insult. After the deaths of many heroes, including the Achaeans Achilles and Ajax, and the Trojans Hector and Paris, the city fell to the ruse of the Trojan Horse. The Achaeans slaughtered the Trojans (except for some of the women and children whom they kept or sold as slaves) and desecrated the temples, thus earning the gods' wrath. Few of the Achaeans returned safely to their homes and many founded colonies in distant shores. The Romans later traced their origin to Aeneas, one of the Trojans, who was said to have led the surviving Trojans to modern day Italy.

This dagger comes from that that great historical period, from the time of the birth of known recorded history, and the formation of great empires, the cradle of civilization, known as The Mycenaean Age, of 1600 BC to 1100 BC. Known as the Bronze Age, it started even centuries before the time of Herodotus, who was known throught the world as the father of history. Mycenae is an archaeological site in Greece from which the name Mycenaean Age is derived. The Mycenae site is located in the Peloponnese of Southern Greece. The remains of a Mycenaean palace were found at this site, accounting for its importance. Other notable sites during the Mycenaean Age include Athens, Thebes, Pylos and Tiryns.

According to Homer, the Mycenaean civilization is dedicated to King Agamemnon who led the Greeks in the Trojan War. The palace found at Mycenae matches Homer's description of Agamemnon's residence. The amount and quality of possessions found at the graves at the site provide an insight to the affluence and prosperity of the Mycenaean civilization. Prior to the Mycenaean's ascendancy in Greece, the Minoan culture was dominant. However, the Mycenaeans defeated the Minoans, acquiring the city of Troy in the process. In the greatest collections of the bronze age there are daggers exactly as this beautiful example. In the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the bronze sword of King Adad-nirari I, a unique example from the palace of one of the early kings of the period (14th-13th century BC) during which Assyria first began to play a prominent part in Mesopotamian history. Swords and daggers from this era were made in the Persian bronze industry, which was also influenced by Mesopotamia. Luristan, near the western border of Persia, it is the source of many bronzes, such as this dagger, that have been dated from 1500 to 500 BC and include chariot or harness fittings, rein rings, elaborate horse bits, and various decorative rings, as well as weapons, personal ornaments, different types of cult objects, and a number of household vessels.

An edged weapon found in the palace of Mallia and dated to the Middle Minoan period (2000-1600 BC), is an example of the extraordinary skill of the Cretan metalworker in casting bronze. The hilt of the weapon is of gold-plated ivory and crystal. A dagger blade found in the Lasithi plain, dating about 1800 BC (Metropolitan Museum of Art), is the earliest known predecessor of ornamented dagger blades from Mycenae. It is engraved with two spirited scenes: a fight between two bulls and a man spearing a boar. Somewhat later (c. 1400 BC) are a series of splendid blades from mainland Greece, which must be attributed to Cretan craftsmen, with ornament in relief, incised, or inlaid with varicoloured metals, gold, silver, and niello. The most elaborate inlays--pictures of men hunting lions and of cats hunting birds--are on daggers from the shaft graves of Mycenae, Nilotic scenes showing Egyptian influence. The bronze was oxidized to a blackish-brown tint; the gold inlays were hammered in and polished and the details then engraved on them. The gold was in two colours, a deeper red being obtained by an admixture of copper; and there was a sparing use of neillo. The copper and gold most likely came from the early mine centres, in and around Mesopotamia, see gallery and the copper ingots exported to the Cretans for their master weapon makers. This dagger is in very nice condition with a single fracture one one side of the hilt 14.75 inches long overall. read more

1395.00 GBP

A Fabulous, Original, Museum Piece, A Medieval Knight's 13th to 15th Century Long Dagger From the Time of the Plantagenet & Lancastrian Kings, From Henry IIIrd, Edwards I/II/III, Richard IInd to King Henry IVth, & King Henry Vth's Battle of Agincourt

Worthy of a world class collection of fine and early arms and armour, or a single statement piece as a compliment to any form of home decor from traditional to ultra contemporary. A piece that would be the centre of conversation and attraction in any location. A most rarely seen, original, complete, & intact, long dagger or short sword of the medieval period, used from the reigns of King Henry IIIrd to King Henry Vth, from the era of the Crusades and the Templar Knights, right through to the Anglo French Battles, the Victories of England against France, at the Battle of Crecy, in 1346, by King Edward IInd and His son the Black Prince, and later at the Battle of Poitiers, in 1356, the victory of King Edward IInd's son, the Black Prince, and King Henry Vth's victory at Agincourt, in 1415.

Daggers surviving from this ancient era are most rare, substantially more rare in fact than the swords themselves. Items such as this were oft acquired in the 18th century by British noblemen touring Northern France and Italy on their Grand Tour. Originally placed on display in the family 'cabinet of curiosities', within his country house upon his return home. A popular pastime in the 18th and 19th century, comprised of English ladies and gentlemen traveling for many months, or even years, througout classical Europe, acquiring antiquities and antiques for their private collections. This dagger's history travels from the English Plantagenet Kings Henry IIIrd, Edward 1st, Edward IInd, Edward IIIrd, & Richard IInd, to the Lancastrian Kings Henry IVth & Henry Vth including use at The Battle of Agincourt, where King Henry carried a near identical dagger and his longer version matched sword that are part of his achievements, hanging above his tomb at Westminster Abbey.

A very fine and very rare museum grade medieval knight's long dagger, with large segmented circular pommel, used for a period of around three centuries from the 13th to 15th century.

An iron double edged dagger with lentoid section tapering blade, curved quillon crossguard and scrolled ends, with narrow tang and with an impressive large segmented wheel pommel.

The Battle of Agincourt was a major English victory in the Hundred Years' War. The battle took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) in the County of Saint-Pol, Artois, some 40 km south of Calais. Along with the battles of Crecy (1346) and Poitiers (1356), it was one of the most important English triumphs in the conflict. England's victory at Agincourt against a numerically superior French army crippled France, and started a new period in the war during which the English began enjoying great military successes.

After several decades of relative peace, the English had renewed their war effort in 1415 amid the failure of negotiations with the French. In the ensuing campaign, many soldiers perished due to disease and the English numbers dwindled, but as they tried to withdraw to English-held Calais they found their path blocked by a considerably larger French army. Despite the disadvantage, the following battle ended in an overwhelming tactical victory for the English.

King Henry V of England led his troops into battle and participated in hand-to-hand fighting. The French king of the time, Charles VI, did not command the French army himself, as he suffered from severe psychotic illnesses with moderate mental incapacitation. Instead, the French were commanded by Constable Charles d'Albret and various prominent French noblemen of the Armagnac party.

This battle is notable for the use of the English longbow in very large numbers, with the English and Welsh archers forming up to 80 percent of Henry's army. The decimation of the French cavalry at their hands is regarded as an indicator of the decline of cavalry and the beginning of the dominance of ranged weapons on the battlefield.

Agincourt is one of England's most celebrated victories. The battle is the centre-piece of the play Henry V by William Shakespeare. Juliet Barker in her book Agincourt: The King, the Campaign, the Battle ( published in 2005) argues the English and Welsh were outnumbered "at least four to one and possibly as much as six to one". She suggests figures of about 6,000 for the English and 36,000 for the French, based on the Gesta Henrici's figures of 5,000 archers and 900 men-at-arms for the English, and Jean de Wavrin's statement "that the French were six times more numerous than the English". The 2009 Encyclopaedia Britannica uses the figures of about 6,000 for the English and 20,000 to 30,000 for the French. Overall 20.5 inches long in very sound and nice condition for age. There are very few such surviving long daggers from this era, and just a few are part of the Royal Collection. As with almost all surviving daggers and swords of this age, none have their wooden grips remaining, and as such the surviving crossguards are somewhat mobile.

A fine example piece, from the ancient knightly age, from almost a thousand years past. Although this dagger is now in an obvious ancient, and historical, russetted condition, every item made of iron from this era, such as the rarest of swords and daggers, even in the Royal Collection, are in this very same state of preservation.

This piece will come with a complimentary display stand, but could also look spectacular suitably framed. We are delighted to offer such a service if required. read more

9750.00 GBP

A Stunning Italian 'Order of the Crown of Italy' in Gold; Knight's Cross Medal. With Polychrome Transluscent Enamel Of The Crown Of Savoy

In Gold and enamels, 37 x 39mm, enamels superbly intact without chipping, original ribbon, extremely fine condition. Gold-edged white enamel cross pattee alisee with gold knots between the arms, on laterally-pierced ball suspension; the face with a circular central deep blue translucent enamel medallion bearing the gilt crown of Savoy with red, with white and green jewels, encircled by a gold ring; the reverse with a gold circular central medallion bearing a crowned black enamel eagle, an oval red enamel shield with a white enamel cross on its breast; The Order of the Crown of Italy was founded as a national order in 1868 by King Vittorio Emanuel II, to commemorate the unification of Italy in 1861. It was awarded in five degrees for civilian and military merit.

Compared with the older Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (1572), the Order of the Crown of Italy was awarded more liberally and could be conferred on non-Catholics as well; eventually, it became a requirement for a person to have already received the Order of the Crown of Italy in at least the same degree before receiving the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus.

The order has been suppressed by law since the foundation of the Republic in 1946. However, Umberto II did not abdicate his position as fons honorum and it remained under his Grand Mastership as a dynastic order. While the continued use of those decorations conferred prior to 1951 is permitted in Italy, the crowns on the ribbons issued before 1946 must be substituted for as many five pointed stars on military uniforms. Following the demise of the last reigning monarch in 1983, the order, founded by the first, is no longer bestowed. Notable recipients of the order were; Major General Robert A. McClure, father of U.S. Army Special Operations, Director of Information and Media Control at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) during World War II

Brigadier General Billy Mitchell, United States Army air power advocate.

Charles Poletti, Governor of New York, and Colonel in the United States Army; served in Italy during World War II. Painting in the gallery by Karel Zadnik (1847-1929), painted in Bilowitz in 1912 of Count Hugo II Logothetti who is wearing his Italian Order of the Crown of Italy around his neck. Silk ribbon with small old staining. read more

225.00 GBP

A Very Fine, Late Middle Ages, Early Hand-Bombard, Iron Mortar Cannon. The Earliest Form of Ignition Battle Weapon That Developed into The Hand Pistole & Blunderbuss

Used in both the field of combat or from a castle battlement. This fine piece would make a wonderful display piece, perhaps set on a small plinth. Ideal for a desk, bookshelf or mantle.

The weapon that provided the name to the Royal Artillery rank of bombardier, and the word 'bombardment'.

A hand bombard was the larger version of the handgonne or hand cannon, yes still a good size for handling.

Small enough and light enough to be manoeuvred by hand and thus then loosely fixed, or semi-permanently fixed, in either an L shaped wooden block and used like a mortar, or, onto a length of sturdy wooden haft, from three feet to five foot long to be used almost musket like and bound with wrought iron bands see illustration in the photo gallery of these medievil variations of mounting. The precursor to the modern day pistol and musket from which this form of ancient so called handgonne developed into over the centuries. It is thought that gunpowder was invented in China and found its way to Europe in the 13th Century. In the mid to late 13th Century gunpowder began to be used in cannons and handguns, and by the mid 14th Century they were in relatively common use for castle sieges. By the end of the 14th Century both gunpowder, guns and cannon had greatly evolved and were an essential part of fortifications which were being modified to change arrow slits for gun loops. Bombards and Hand cannon' date of origin ranges around 1350. Hand bombards and hand cannon were relatively inexpensive to manufacture, but the skill required to make them was considerable, but they were not that accurate to fire. Nevertheless, they were employed for their shock value. In 1492 Columbus carried one on his discovery exploration to the Americas.

Conquistadors Hernando Cortez and Francisco Pizzaro also used them, in 1519 and 1533, during their respective conquests and colonization of Mexico and Peru. Not primary arms of war, hand bombards and hand cannon were adequate tools of protection for fighting men.

See Funcken, L. & Funcken F., Le costume, l'armure et les armes au temps de la chevalerie, de huitieme au quinzieme siecle, Tournai,1977, pp.66-69, for reconstruction of how such hand cannons were used.

At the beginning of the 14th century, among the infantry troops of the Western Middle Ages, developed the use of manual cannons (such as the Italian schioppetti, spingarde, and the German Fusstbusse).

Photo of the hand bombard recovered from the well at Cardiff Castle, by Simon Burchell - Own work

External width at the muzzle 3.25 inches, length 8 inches. Weight 10.2 pounds read more

2695.00 GBP

A Superb Original 12th Century Crusader Knights Templar Medieval Knight's Dagger, A Shortened Knightly Sword, with Crucifix Hilt. The Blade Bears The Remains of a Templar Cross, Inlaid, in Gold Alloy Latten, Upon One Blade Face Below The Hilt

Originally made for and used by a Knights Templar, Knight Hospitaller, in the early 12th century as a sword, then, in or around the the same century it was damaged, and reformed by a skilled sword smith, it was shortened and then used as a knightly dagger, very likely continually until the reign of King Henry Vth into the Battle of Agincourt era circa 1415.

Possibly damaged in the second crusade, retained as a family heirloom and historic treasure, to be used as a crucifix form hilted knightly dagger. A millennia ago it would have had a wooden handle but long since rotted away.

See photo 7 in the gallery to show a carved grave stone of a crusader knight who has a the same form of shortened sword cruciform hilted dagger upon his right thigh.

This wonderful original Medieval period antiquity would make a spectacular centre-piece to any new or long established fine collection, or indeed a magnificent solitary work of historical art, for any type of decor both traditional or contemporary. What a fabulous original ‘statement piece’ for any collection or decor. In the world of collecting there is so little remaining in the world from this highly significant era in European and British history. And to be able to own and display such an iconic original representation from this time is nothing short of a remarkable privilege. A wonderful example piece, from the ancient knightly age. Effectively, from this time of almost a thousand years ago, from a collectors point of view, little else significant survives at all, only the odd small coin, ring, or, very rarely seen, and almost impossible to own, carved statuary.

This fabulous dagger was reformed in the medieval crusades period by cutting down the upper third of the sword; the blade being broad, with shallow fuller and square shoulders, the guard narrow and tapering towards the ends; it bears a later formed 'acorn' style pommel. See Oakeshott, E., Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991. 942 grams, 47cm (18 1/2"). From a private family collection; previously acquired from a collection formed before 1990; thence by descent. The weapon started life as a two-edged sword, probably of Oakeshott's Type XV with broad tang and narrow guard. There is a trace of crucifix, inlay, in latten, a gold-bronze alloy, below the shoulder to one face, which likely was a templar crucifix symbol. {see photo 9 in the gallery}

It is likely that the sword was damaged in combat at the time of the post Norman conquests of England, and thereafter, in the early second crusades, and using the damaged knight's long sword, probably in combat during the second crusade in the Holy Land, a large knightly dagger was created, by removing the unusable part, and re-pointing the shortened blade.

This superb piece could only be used by the rank and status of Templar Knight, or, such as Knight Hospitallar ,as the lower orders below knight, were not permitted the use or ownership of fine knightly form swords or daggers

The Knights Templar were an elite fighting force of their day, highly trained, well-equipped, and highly motivated; one of the tenets of their religious order was that they were forbidden from retreating in battle, unless outnumbered three to one, and even then only by order of their commander, or if the Templar flag went down. Not all Knights Templar were warriors. The mission of most of the members was one of support – to acquire resources which could be used to fund and equip the small percentage of members who were fighting on the front lines. There were actually three classes within the orders. The highest class was the knight. When a candidate was sworn into the order, they made the knight a monk. They wore white robes. The knights could hold no property and receive no private letters. They could not be married or betrothed and could not have any vow in any other Order. They could not have debt more than they could pay, and no infirmities. The Templar priest class was similar to the modern day military chaplain. Wearing green robes, they conducted religious services, led prayers, and were assigned record keeping and letter writing. They always wore gloves, unless they were giving Holy Communion. The mounted men-at-arms represented the most common class, and they were called "brothers". They were usually assigned two horses each and held many positions, including guard, steward, squire or other support vocations. As the main support staff, they wore black or brown robes and were partially garbed in chain mail or plate mail. The armour was not as complete as the knights. Because of this infrastructure, the warriors were well-trained and very well armed. Even their horses were trained to fight in combat, fully armoured. The combination of soldier and monk was also a powerful one, as to the Templar knights, martyrdom in battle was one of the most glorious ways to die.

The Templars were also shrewd tacticians, following the dream of Saint Bernard who had declared that a small force, under the right conditions, could defeat a much larger enemy. One of the key battles in which this was demonstrated was in 1177, at the Battle of Montgisard. The famous Muslim military leader Saladin was attempting to push toward Jerusalem from the south, with a force of 26,000 soldiers. He had pinned the forces of Jerusalem's King Baldwin IV, about 500 knights and their supporters, near the coast, at Ascalon. Eighty Templar knights and their own entourage attempted to reinforce. They met Saladin's troops at Gaza, but were considered too small a force to be worth fighting, so Saladin turned his back on them and headed with his army towards Jerusalem.

Once Saladin and his army had moved on, the Templars were able to join King Baldwin's forces, and together they proceeded north along the coast. Saladin had made a key mistake at that point – instead of keeping his forces together, he permitted his army to temporarily spread out and pillage various villages on their way to Jerusalem. The Templars took advantage of this low state of readiness to launch a surprise ambush directly against Saladin and his bodyguard, at Montgisard near Ramla. Saladin's army was spread too thin to adequately defend themselves, and he and his forces were forced to fight a losing battle as they retreated back to the south, ending up with only a tenth of their original number. The battle was not the final one with Saladin, but it bought a year of peace for the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the victory became a heroic legend.

Another key tactic of the Templars was that of the "squadron charge". A small group of knights and their heavily armed warhorses would gather into a tight unit which would gallop full speed at the enemy lines, with a determination and force of will that made it clear that they would rather commit suicide than fall back. This terrifying onslaught would frequently have the desired result of breaking a hole in the enemy lines, thereby giving the other Crusader forces an advantage.

The Templars, though relatively small in number, routinely joined other armies in key battles. They would be the force that would ram through the enemy's front lines at the beginning of a battle, or the fighters that would protect the army from the rear. They fought alongside King Louis VII of France, and King Richard I of England. In addition to battles in Palestine, members of the Order also fought in the Spanish and Portuguese Reconquista.

According to author S.Tibble, and in his new book, Templars, the Knights Who Made Britain, he details a very convincing and gripping history, that the Templars, famous for their battles on Christendom’s eastern front, were in fact dedicated peace-mongers at home. They influenced royal strategy and policy, created financial structures, and brokered international peace treaties—primarily to ensure that men, money, and material could be transferred more readily to the east.

Charting the rise of the Order under Henry I through to its violent suppression following the fall of Acre, Tibble argues that these medieval knights were essential to the emergence of an early English state. Revealing the true legacy of the British Templars, he shows how a small group helped shape medieval Britain while simultaneously fighting in the name of the Christian Middle East

This dagger would have likely been used continually past the era of King Richard for another 200 years into to the 1400's, past the Battle of Crecy and into the Battle of Agincourt era, for knightly swords and daggers were extraordinarily valuable, and simply never discarded unless they were too damaged to use and beyond repair. From the time after Agincourt, knightly dagger patterns changed to become longer and much narrower, with considerably smaller guards. There were three main later dagger types then, called called rondel, ear and ballock. Almost every iron weapon that has survived today from this era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one, because only some of the swords of kings, that have been preserved in national or Royal collections are today still in a fairly good state of preservation and condition. This dagger is certainly in good condition for its age, it’s cross guard is, as usual, mobile, as organic wooden grips almost never survive in weapons of such great age.

Daggers bespoke made or adapted from earlier long swords of this form were clearly used well into the age of Henry Vth as carved marble and stone tombs, or monumental brasses, covering buried knights within churches and cathedrals are often adorned in full armour combined with such knightly daggers and swords, and they are also further depicted at the time in illuminated manuscripts or paintings of knightly battles such as of Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt at the time. read more

5350.00 GBP

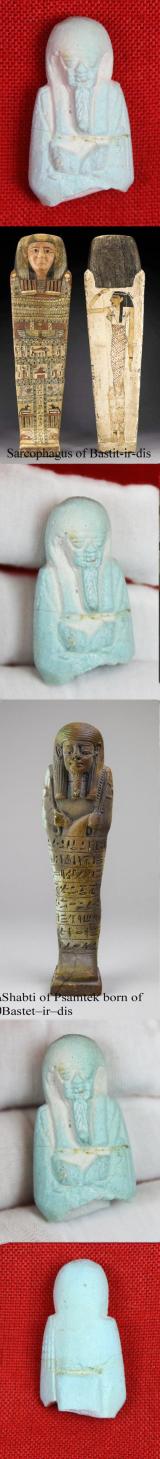

A Finely Detailed Original Ancient Egyptian Shabti a Representation of a Mummified Human Tomb Figure, The Afterlife Servant of the Mummy, in Faience Blue Glazed Late Period, Dynasty XXVI, 664-525 B. C. From the Tomb of the Female Owner Bastet-ir-dis

Around 2500 years old. One of two we acquired, excavated from a tomb, and part of a collection formed before the 1970's. A light blue and green composition shabti comprising the remaining upper body, head and shoulders with crossed arms holding crook and flail, wearing a tripartite wig and false beard, semi-naturalistic detailing to the faces. A shabti (also known as shawabti or ushabti) is a generally mummiform small figurine found in many ancient Egyptian tombs. They are commonly made of blue or green glazed Egyptian faience, but can also consist of stone, wood, clay, metal, and glass.

We had two previously from the same collector that bore an inscription {these latest pair are not inscribed, but came from the same tomb} that included the name of the female owner Bastet-ir-dis (which can be translated as 'it was Bastet who gave it' i.e. the lady was the gift of the goddess Bastet), highlights the popularity of this feline deity during the Late Period and Ptolemaic/Roman times. Bastet was a protector of the sun god Re as well as being associated with motherhood and fertility. Bastet-ir-dis's name is preceded by 'the Osiris', a common appellation in shabti inscriptions of this and earlier periods, which associates the deceased with the preeminent ancient Egyptian god of the Underworld. The name was followed by the epithet 'true of voice' or 'justified', an attestation of the deceased's good character as judged by a divine tribunal that decided whether a person could enter the eternal Hereafter. Then follows the phrase 'born to' which would have been accompanied by the name of Bastet-ir-dis's mother on the now missing portion of these figures.

We show two other shabti found in other tombs of the children of Bastet-ir-dis, plus amazingly the actual sarcophagus of Bastit-ir-dis sold at Christies over 20 years ago, in 2001, for $30,550. Original Egyptian Sarcophagus have increased in desirability in the past 20 odd years exponentially, with some fetching as high as $1,000,000 {likely due because it is now forbidden to remove all antiquities from Egypt}

National Museum of Liverpool Shabti of Psamtek born of Bastet-ir-dis

664 BC - 525 BC (Dynasty 26)

British Museum number

Shabti of Padipep

Named in inscription: Bastet-ir-dis (born of)

An Ancient Egyptian painted Wood Anthropoid Sarcophagus of Bastet-ir-dis

Late Period, Dynasty XXVI, 664-525 B. C.

Gessoed and painted depicting the deceased, the lady Bastet-irdis, wearing a striated vulture cap covered wig, and a falcon terminated broad collar, the entire surface of the lid with mythological vignettes, funerary deities and their accompanying inscriptions, the principle among which are a kneeling, winged Isis, and the deceased on a bier; the join of the lid to the box decorated with an undulating serpent, the box with two long funerary offering formulae for the benefit of Bastet-irdis, the back with a profile figure of the "Goddess of the West" Sold originally in the Antiquitie sale, Sotheby's London, 8 December 1994, lot 100

The inscription includes the name of the female owner Bastet-ir-dis (which can be translated as 'it was Bastet who gave it' i.e. the lady was the gift of the goddess Bastet), highlights the popularity of this feline deity during the Late Period and Ptolemaic/Roman times. Bastet was a protector of the sun god Re as well as being associated with motherhood and fertility. Bastet-ir-dis's name is preceded by 'the Osiris', a common appellation in shabti inscriptions of this and earlier periods, which associates the deceased with the preeminent ancient Egyptian god of the Underworld. The name is followed by the epithet 'true of voice' or 'justified', an attestation of the deceased's good character as judged by a divine tribunal that decided whether a person could enter the eternal Hereafter. Then follows the phrase 'born to' which would have been accompanied by the name of Bastet-ir-dis's mother on the now missing portion of these figures.

The meaning of the Egyptian term is still debated, however one possible translation is ‘answerer’, as they were believed to answer their master’s call to work in the afterlife. Since the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BC), for instance, the deceased were buried with servant statuettes like bakers and butchers, providing their owners with eternal sustenance. after the death of Cleopatra in around 37 b.c. and the close of the Ptolomeic Dynasty, no shabti were produced for service in Egyptian mummy's tombs. A spell was oft written on the shabti so that it would awaken as planned, this is the 'shabti spell' from chapter six of the Book of the Dead and reads as follows:

"O shawabti, if name of deceased is called upon,

If he is appointed to do any work which is done on the necropolis,

Even as the man is bounden, namely to cultivate the fields,

To flood the river-banks or to carry the sand of the East to the West,

And back again, then 'Here am I!' you shall say"1

2,000 to 2300 years old. From the Last pharoes of Egypt, that lasted for 275 years, up to the era of Julius Caeser, Cleopatra and Mark Anthony. With The last pharoah almost being the son of Julius Caeser, Caesarian but his mother famously committed suicide, and with the death of Cleopatra, thus the pharoic dynasties ended. Egyptian Blue Glazed Faience Ptolemaic dynasty sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty after Ptolemy I's father, who was a Macedonian Greek

The royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 to 30 BC. The Ptolemaic was the last dynasty of ancient Egypt.

Ptolemy, one of the seven somatophylakes (bodyguard companions), a general and possible half-brother of Alexander the Great was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself Pharaoh Ptolemy I, later known as Sōter "Saviour". The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC.

Like the earlier dynasties of ancient Egypt, the Ptolemaic dynasty practised inbreeding including sibling marriage, but this did not start in earnest until nearly a century into the dynasty's history. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy, while queens regnant were all called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land.

1.3/4"). Fair condition very old repair to mid section. read more

395.00 GBP

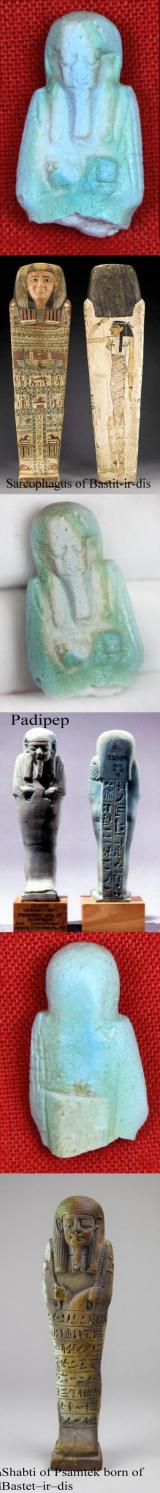

A Finally Detailed Original Ancient Egyptian Shabti a Representation of a Mummified Human Tomb Figure, The Afterlife Servant of the Mummy, in Faience Blue Glazed Late Period, Dynasty XXVI, 664-525 B. C. From the Tomb of the Female Owner Bastet-ir-dis

Around 2500 years old. One of two we acquired, for sale seperately, excavated from a tomb, and part of a collection formed before the 1970's. A light blue and green composition shabti comprising the remaining upper body, head and shoulders with crossed arms holding crook and flail, wearing wig and false beard, semi-naturalistic detailing to the faces.

We had two previously from the same collector that bore an inscription {these latest pair are not inscribed, but came from the same tomb} that included the name of the female owner Bastet-ir-dis (which can be translated as 'it was Bastet who gave it' i.e. the lady was the gift of the goddess Bastet), highlights the popularity of this feline deity during the Late Period and Ptolemaic/Roman times. Bastet was a protector of the sun god Re as well as being associated with motherhood and fertility. Bastet-ir-dis's name is preceded by 'the Osiris', a common appellation in shabti inscriptions of this and earlier periods, which associates the deceased with the preeminent ancient Egyptian god of the Underworld. The name was followed by the epithet 'true of voice' or 'justified', an attestation of the deceased's good character as judged by a divine tribunal that decided whether a person could enter the eternal Hereafter. Then follows the phrase 'born to' which would have been accompanied by the name of Bastet-ir-dis's mother on the now missing portion of these figures.

We show two other shabti found in other tombs of the children of Bastet-ir-dis, plus amazingly the actual sarcophagus of Bastit-ir-dis sold at Christies over 20 years ago, in 2001, for $30,550. Original Egyptian Sarcophagus have increased in desirability in the past 20 odd years exponentially, with some fetching as high as $1,000,000 {likely due because it is now forbidden to remove all antiquities from Egypt}

National Museum of Liverpool Shabti of Psamtek born of Bastet-ir-dis

664 BC - 525 BC (Dynasty 26)

British Museum number

Shabti of Padipep

Named in inscription: Bastet-ir-dis (born of)

An Ancient Egyptian painted Wood Anthropoid Sarcophagus of Bastet-ir-dis

Late Period, Dynasty XXVI, 664-525 B. C.

Gessoed and painted depicting the deceased, the lady Bastet-irdis, wearing a striated vulture cap covered wig, and a falcon terminated broad collar, the entire surface of the lid with mythological vignettes, funerary deities and their accompanying inscriptions, the principle among which are a kneeling, winged Isis, and the deceased on a bier; the join of the lid to the box decorated with an undulating serpent, the box with two long funerary offering formulae for the benefit of Bastet-irdis, the back with a profile figure of the "Goddess of the West" Sold originally in the Antiquitie sale, Sotheby's London, 8 December 1994, lot 100

The inscription includes the name of the female owner Bastet-ir-dis (which can be translated as 'it was Bastet who gave it' i.e. the lady was the gift of the goddess Bastet), highlights the popularity of this feline deity during the Late Period and Ptolemaic/Roman times. Bastet was a protector of the sun god Re as well as being associated with motherhood and fertility. Bastet-ir-dis's name is preceded by 'the Osiris', a common appellation in shabti inscriptions of this and earlier periods, which associates the deceased with the preeminent ancient Egyptian god of the Underworld. The name is followed by the epithet 'true of voice' or 'justified', an attestation of the deceased's good character as judged by a divine tribunal that decided whether a person could enter the eternal Hereafter. Then follows the phrase 'born to' which would have been accompanied by the name of Bastet-ir-dis's mother on the now missing portion of these figures.

A shabti (also known as shawabti or ushabti) is a generally mummiform small figurine found in many ancient Egyptian tombs. They are commonly made of blue or green glazed Egyptian faience, but can also consist of stone, wood, clay, metal, and glass. The meaning of the Egyptian term is still debated, however one possible translation is ‘answerer’, as they were believed to answer their master’s call to work in the afterlife. Since the Fourth Dynasty (2613–2494 BC), for instance, the deceased were buried with servant statuettes like bakers and butchers, providing their owners with eternal sustenance. after the death of Cleopatra in around 37 b.c. and the close of the Ptolomeic Dynasty, no shabti were produced for service in Egyptian mummy's tombs. A spell was oft written on the shabti so that it would awaken as planned, this is the 'shabti spell' from chapter six of the Book of the Dead and reads as follows:

"O shawabti, if name of deceased is called upon,

If he is appointed to do any work which is done on the necropolis,

Even as the man is bounden, namely to cultivate the fields,

To flood the river-banks or to carry the sand of the East to the West,

And back again, then 'Here am I!' you shall say"

2500 years old, the 26th dynasty 664-525 B.C. fortified the culture, which saw a new phase of artistic expression in stone monuments and statuary. Later generations would remember this dynasty as representative of Egyptian history, and would in turn recapitulate Saite forms. From the era around 200 years before the last pharoes of Egypt, known as the Ptolomeic Dynasty that lasted for 275 years, up to the era of Julius Caeser, Cleopatra and Mark Anthony. With The last pharoah almost being the son of Julius Caeser, Caesarian but his mother famously committed suicide, and with the death of Cleopatra, thus the pharoic dynasties ended.

The Ptolemaic dynasty is sometimes referred to as the Lagid dynasty after Ptolemy I's father, who was a Macedonian Greek

The royal dynasty which ruled the Ptolemaic Kingdom in Ancient Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 to 30 BC. The Ptolemaic was the last dynasty of ancient Egypt.

Ptolemy, one of the seven somatophylakes (bodyguard companions), a general and possible half-brother of Alexander the Great was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself Pharaoh Ptolemy I, later known as Sōter "Saviour". The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC.

Like the earlier dynasties of ancient Egypt, the Ptolemaic dynasty practiced inbreeding including sibling marriage, but this did not start in earnest until nearly a century into the dynasty's history. All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy, while queens regnant were all called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

Grand Tour souvenirs included a wide variety of sculpture, paintings, and antiquities, and led to Egyptian artefacts being found in the most unexpected places. Today’s visitors to historic houses, like those managed by the National Trust in Great Britain, may encounter an incongruous Egyptian item, like the top part of a small basalt figure, described as a nomarch, on a bedroom chimneypiece at Petworth House, Sussex, or the kneeling statue of Ramesses II on the staircase at The Vyne, Hampshire. Quite possibly, there will be no indication of the object’s age, origins, or purpose. If the visitor is lucky, they will find a display label, or an entry in a guidebook or online catalogue, but the history behind the object’s presence is more commonly unexplained.

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land.

1 1/2" inches high. Fair condition. read more

445.00 GBP

Archaic Zhou Dynasty Bronze Halberd or ‘Ge’ of a Zhou Dynasty Charioteer, Circa 5th Century BC. Used By a Warrior In the Period of the Great Military Doctrine 'The Art of War' by General Sun-Tzu

This is the very type of original ancient ceremonial halbard, defined by the ancient Chinese as a dagger axe 'Ge' and exactly the type as used by the warriors serving under the world renowned General Sun Tzu, in the Kingdom of Wu, who is thought by many to be the finest general, philosopher and military tactician who ever lived. His 2500 year old book on the methods of warfare, tactics and psychology are still taught and highly revered in practically every officer training college throughout the world.

In excavated condition, cast in one piece, slightly curved terminal blade of thin flattened-diamond section, pierced along a basal flange with three slots, with fabulous areas of crystallized malachite, blue/green patina.

We also show in the gallery a schematic of how this 'Ge' halbard would have been mounted 2500 odd years ago on its long haft, and used by a charioteer warrior, there is also one depicted being carried in a painting that we show in the gallery being used in a chariot charge in the Zhou dynasty.

This is a superb original ancient piece from one of the great eras of Chinese history. it is unsigned but near identical to another that was signed and inscribed with details that have now been fully translated, deciphered and a few years ago shown at Sothebys New York estimated to a sale value of $300,000. Its research details are fully listed below, and it is photographed within our gallery for the viewers comparison. Naturally, our un-inscribed, but still, very rare original version, from the same era and place, is a much more affordable fraction of this price

The signed and named Sotheby's of New York example that we show in the gallery, was formerly made for its original warrior owner, Qu Shutuo of Chu, it is from the same period and in similar condition as ours. We reference it's description below, and it is photographed within the gallery, it is finely cast with the elongated yuan divided by a raised ridge in the middle of each side and extending downward to form the hu, inscribed to one side with eight characters reading Chu Qu Shutuo, Qu X zhisun, all bordered by sharply finished edges, the end pierced with three vertically arranged chuan (apertures), the nei with a further rectangular chuan and decorated with hook motifs, inscribed to one side with seven characters reading Chuwang zhi yuanyou, wang zhong, and the other side with five characters reading yu fou zhi X sheng, the surface patinated to a dark silver tone with light malachite encrustation

An Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Ritual Bronzes. Loaned by C.T. Loo & Co., The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1940, pl. XXXIII.

New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, March - June 1948.

This inscribed bronze halberd blade, although typical in form, is uniquely important as its inscription serves as a critical primary source that reveals the name of its original owner: Qu Shutuo of Chu. The only known close counterpart to this blade is a damaged bronze halberd blade, missing the yuan, and inscribed on the hu with seven characters, which can be generally translated to ‘for the auspicious use of Qu Shutuo of Chu’. That halberd is now in the collection of the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, and published in Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng Compendium of inscriptions and images of bronzes from Shang and Zhou dynasties, vol. 32, Shanghai, 2012, no. 17048

The remaining thirteen inscriptions can be translated as: 'Qu Shutuo of Chu, Qu X's grandson, yuanyou of the King of Chu'. Based on the inscription, the owner of this blade can be identified as such.

See for reference; The Junkunc Collection: Arts of Ancient China / Sotheby's New York

Lot 111

We also show in the gallery a photo of another similar halberd from a museum exhibition, of a Chinese ancient king bodyguard’s halberd gilt pole mounts for his personal charioteer

This is one of a stunning collection of original archaic bronze age weaponry we have just acquired. Many are near identical to other similar examples held in the Metropolitan in New York, the British royal collection, and such as the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, China. As with all our items, every piece is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. read more

1850.00 GBP