A Superb Original 12th Century Crusader Knights Templar Medieval Knight's Dagger, A Shortened Knightly Sword, with Crucifix Hilt. The Blade Bears The Remains of a Templar Cross, Inlaid, in Gold Alloy Latten, Upon One Blade Face Below The Hilt

Originally made for and used by a Knights Templar, Knight Hospitaller, in the early 12th century as a sword, then, in or around the the same century it was damaged, and reformed by a skilled sword smith, it was shortened and then used as a knightly dagger, very likely continually until the reign of King Henry Vth into the Battle of Agincourt era circa 1415.

Possibly damaged in the second crusade, retained as a family heirloom and historic treasure, to be used as a crucifix form hilted knightly dagger. A millennia ago it would have had a wooden handle but long since rotted away.

See photo 7 in the gallery to show a carved grave stone of a crusader knight who has a the same form of shortened sword cruciform hilted dagger upon his right thigh.

This wonderful original Medieval period antiquity would make a spectacular centre-piece to any new or long established fine collection, or indeed a magnificent solitary work of historical art, for any type of decor both traditional or contemporary. What a fabulous original ‘statement piece’ for any collection or decor. In the world of collecting there is so little remaining in the world from this highly significant era in European and British history. And to be able to own and display such an iconic original representation from this time is nothing short of a remarkable privilege. A wonderful example piece, from the ancient knightly age. Effectively, from this time of almost a thousand years ago, from a collectors point of view, little else significant survives at all, only the odd small coin, ring, or, very rarely seen, and almost impossible to own, carved statuary.

This fabulous dagger was reformed in the medieval crusades period by cutting down the upper third of the sword; the blade being broad, with shallow fuller and square shoulders, the guard narrow and tapering towards the ends; it bears a later formed 'acorn' style pommel. See Oakeshott, E., Records of the Medieval Sword, Woodbridge, 1991. 942 grams, 47cm (18 1/2"). From a private family collection; previously acquired from a collection formed before 1990; thence by descent. The weapon started life as a two-edged sword, probably of Oakeshott's Type XV with broad tang and narrow guard. There is a trace of crucifix, inlay, in latten, a gold-bronze alloy, below the shoulder to one face, which likely was a templar crucifix symbol. {see photo 9 in the gallery}

It is likely that the sword was damaged in combat at the time of the post Norman conquests of England, and thereafter, in the early second crusades, and using the damaged knight's long sword, probably in combat during the second crusade in the Holy Land, a large knightly dagger was created, by removing the unusable part, and re-pointing the shortened blade.

This superb piece could only be used by the rank and status of Templar Knight, or, such as Knight Hospitallar ,as the lower orders below knight, were not permitted the use or ownership of fine knightly form swords or daggers

The Knights Templar were an elite fighting force of their day, highly trained, well-equipped, and highly motivated; one of the tenets of their religious order was that they were forbidden from retreating in battle, unless outnumbered three to one, and even then only by order of their commander, or if the Templar flag went down. Not all Knights Templar were warriors. The mission of most of the members was one of support – to acquire resources which could be used to fund and equip the small percentage of members who were fighting on the front lines. There were actually three classes within the orders. The highest class was the knight. When a candidate was sworn into the order, they made the knight a monk. They wore white robes. The knights could hold no property and receive no private letters. They could not be married or betrothed and could not have any vow in any other Order. They could not have debt more than they could pay, and no infirmities. The Templar priest class was similar to the modern day military chaplain. Wearing green robes, they conducted religious services, led prayers, and were assigned record keeping and letter writing. They always wore gloves, unless they were giving Holy Communion. The mounted men-at-arms represented the most common class, and they were called "brothers". They were usually assigned two horses each and held many positions, including guard, steward, squire or other support vocations. As the main support staff, they wore black or brown robes and were partially garbed in chain mail or plate mail. The armour was not as complete as the knights. Because of this infrastructure, the warriors were well-trained and very well armed. Even their horses were trained to fight in combat, fully armoured. The combination of soldier and monk was also a powerful one, as to the Templar knights, martyrdom in battle was one of the most glorious ways to die.

The Templars were also shrewd tacticians, following the dream of Saint Bernard who had declared that a small force, under the right conditions, could defeat a much larger enemy. One of the key battles in which this was demonstrated was in 1177, at the Battle of Montgisard. The famous Muslim military leader Saladin was attempting to push toward Jerusalem from the south, with a force of 26,000 soldiers. He had pinned the forces of Jerusalem's King Baldwin IV, about 500 knights and their supporters, near the coast, at Ascalon. Eighty Templar knights and their own entourage attempted to reinforce. They met Saladin's troops at Gaza, but were considered too small a force to be worth fighting, so Saladin turned his back on them and headed with his army towards Jerusalem.

Once Saladin and his army had moved on, the Templars were able to join King Baldwin's forces, and together they proceeded north along the coast. Saladin had made a key mistake at that point – instead of keeping his forces together, he permitted his army to temporarily spread out and pillage various villages on their way to Jerusalem. The Templars took advantage of this low state of readiness to launch a surprise ambush directly against Saladin and his bodyguard, at Montgisard near Ramla. Saladin's army was spread too thin to adequately defend themselves, and he and his forces were forced to fight a losing battle as they retreated back to the south, ending up with only a tenth of their original number. The battle was not the final one with Saladin, but it bought a year of peace for the Kingdom of Jerusalem, and the victory became a heroic legend.

Another key tactic of the Templars was that of the "squadron charge". A small group of knights and their heavily armed warhorses would gather into a tight unit which would gallop full speed at the enemy lines, with a determination and force of will that made it clear that they would rather commit suicide than fall back. This terrifying onslaught would frequently have the desired result of breaking a hole in the enemy lines, thereby giving the other Crusader forces an advantage.

The Templars, though relatively small in number, routinely joined other armies in key battles. They would be the force that would ram through the enemy's front lines at the beginning of a battle, or the fighters that would protect the army from the rear. They fought alongside King Louis VII of France, and King Richard I of England. In addition to battles in Palestine, members of the Order also fought in the Spanish and Portuguese Reconquista.

According to author S.Tibble, and in his new book, Templars, the Knights Who Made Britain, he details a very convincing and gripping history, that the Templars, famous for their battles on Christendom’s eastern front, were in fact dedicated peace-mongers at home. They influenced royal strategy and policy, created financial structures, and brokered international peace treaties—primarily to ensure that men, money, and material could be transferred more readily to the east.

Charting the rise of the Order under Henry I through to its violent suppression following the fall of Acre, Tibble argues that these medieval knights were essential to the emergence of an early English state. Revealing the true legacy of the British Templars, he shows how a small group helped shape medieval Britain while simultaneously fighting in the name of the Christian Middle East

This dagger would have likely been used continually past the era of King Richard for another 200 years into to the 1400's, past the Battle of Crecy and into the Battle of Agincourt era, for knightly swords and daggers were extraordinarily valuable, and simply never discarded unless they were too damaged to use and beyond repair. From the time after Agincourt, knightly dagger patterns changed to become longer and much narrower, with considerably smaller guards. There were three main later dagger types then, called called rondel, ear and ballock. Almost every iron weapon that has survived today from this era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one, because only some of the swords of kings, that have been preserved in national or Royal collections are today still in a fairly good state of preservation and condition. This dagger is certainly in good condition for its age, it’s cross guard is, as usual, mobile, as organic wooden grips almost never survive in weapons of such great age.

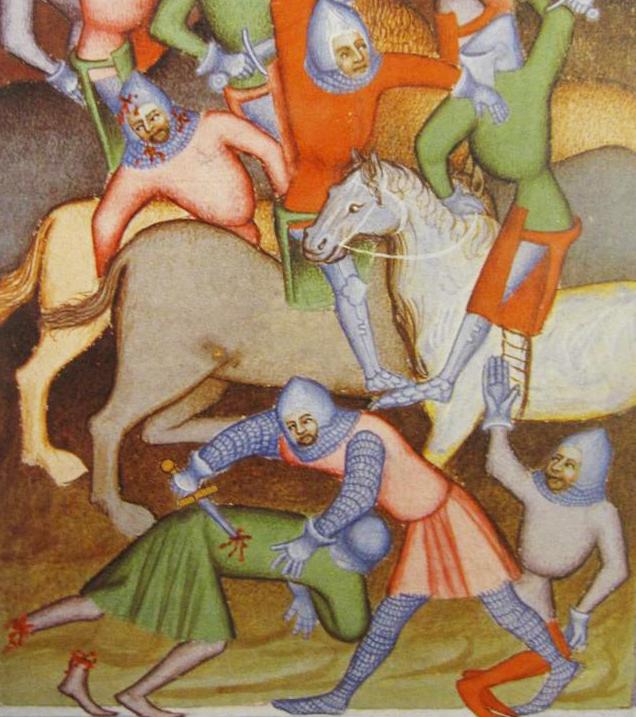

Daggers bespoke made or adapted from earlier long swords of this form were clearly used well into the age of Henry Vth as carved marble and stone tombs, or monumental brasses, covering buried knights within churches and cathedrals are often adorned in full armour combined with such knightly daggers and swords, and they are also further depicted at the time in illuminated manuscripts or paintings of knightly battles such as of Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt at the time.

Code: 23420

5350.00 GBP