Antique Arms & Militaria

A 19th Century, Highly Attractive, Antique Stilletto Bladed So-Called Courtesan's Protective Dagger

Spiral carved bone hilt, powerful quatrefoil 'armour piercing' blade, steel teardrop quillon crossguard, nickle scabbard. A so called coutesan's dagger, also often regarded as the gambler's boot dagger when found in North America

A coutesan's dagger was so called due to their attractiveness and useful size for concealment by unaccompanied ladies travelling abroad after dark.

Of course they would never have been sold as such by retailers, and the term has entered the vernacular of collectors probably even after the time they were actually made, however, like the term 'mortuary hilted swords' that bore the engraved visage of the king in the hilt from the English Civil War, they were never actually called that until almost 200 years later.

They are attractively designed elegant daggers, just such as this one, with a powerful and most efficient blade. 'Ladies of the night' became a major concern and a focal point for social reformers in the 19th century. Concerns were seen everywhere including the literature of notables such as Charles Dickens. He created characters (some of which may have had real life versions) like Nancy in Oliver Twist, and Martha Endell in David Copperfield.

No one knows for certain, but there were somewhere between 8,000 and 80,000 ladies of the trade in London during the Victorian Age. It is generally accepted that most of these women found themselves in prostitution due to economic necessity and desperate want.

There were three attitudes towards those in the profession – condemnation, regulation, and reformation. Dickens adopted the last and was intimately involved in a house of reform called Urania Cottage.

The carved handle has some feint natural line age markings read more

675.00 GBP

A Rare Victorian 2nd Regiment NSW Volunteer Infantry Helmet Badge Circa

Circa 1878. Silvered brass hat badge with centrally mounted Maltese cross featuring a number '2' within a circle in the centre. The cross is surmounted by a large Kings Crown and surrounded by a wreath of waratahs with intertwined scrolls. The scroll on the left reads 'NUMERO SECUNDUS' and the right scroll reads 'NULLI SECUNDUS'. Beneath the cross on a central scroll is 'VIRTUTE' and 'SECOND REGT INFANTRY'. The back of the badge has three lugs for attaching it to the hat. They have a near identical example in the Australian War Memorial Collection that may be associated with the Ferguson family from Goulburn as it was found in the personal affects of 9146 Gunner Leopold Ferguson who was killed on 9 June 1917 while serving with the Australian Imperial Force. read more

295.00 GBP

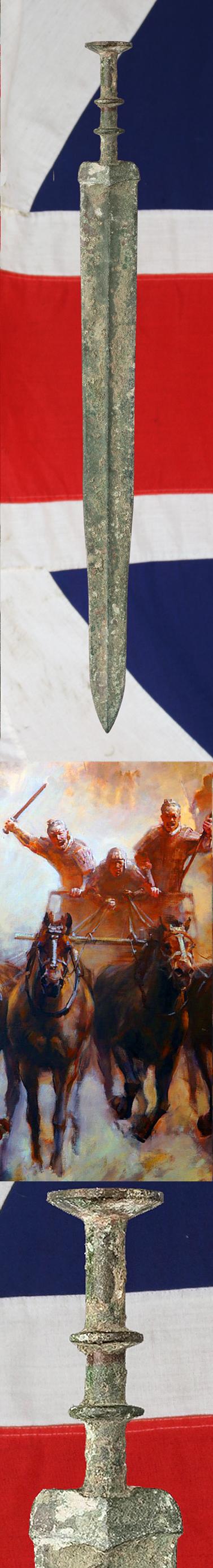

Archaic Chinese Warrior's Bronze Sword, Around 2,300 to 2,800 Years Old, From the Zhou Dynasty to the Qin Dynasty, Including the Period of the Great Military Doctrine 'The Art of War' by General Sun-Tzu

Chinese Bronze 'Two Ring' Jian sword used in the era of the Seven Kingdoms period, likely in the Kingdom of Wu, up to the latter part of the Eastern Zhou dynasty (475 – 221 BC).

Swords of this type are called “two-ring” swords because of the prominent rings located on the hilt. this is the very type of sword used by the warriors serving under the world renowned General Sun Tzu, in the Kingdom of Wu, who is thought by many to be the finest general, philosopher and military tactician who ever lived. His 2500 year old book on the methods of warfare, tactics and psychology are still taught and highly revered in practically every officer training college throughout the world.

We show a painting in the gallery of a chariot charge by a Zhou dynasty warrior armed with this very form of sword.

The Chinese term for this form of weapon is “Jian” which refers to a double-edged sword. This style of Jian is generally attributed to either the Wu or the Yue state. The sword has straight graduated edges reducing to a pointed tip, which may indicate an earlier period Jian.

The blade is heavy with a midrib and tapered edges

A very impressive original ancient Chinese sword with a long, straight blade with a raised, linear ridge down its centre. It has a very shallow, short guard. The thin handle would have had leather or some other organic material such as leather or hemp cord, wrapped around it to form a grip. At the top is a broad, round pommel The Seven Kingdom or Warring States period in Chinese history was one of instability and conflict between many smaller Kingdom-states. The period officially ended when China was unified under the first Emperor of China, Qin pronounced Chin Shi Huang Di in 221 BC. It is from him that China gained its name.

The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) was among the most culturally significant of the early Chinese dynasties and the longest lasting of any in China's history, divided into two periods: Western Zhou (1046-771 BCE) and Eastern Zhou (771-256 BCE). It followed the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600-1046 BCE), and preceded the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE, pronounced “chin”) which gave China its name.

In the early years of the Spring and Autumn Period, (770-476 BC) chivalry in battle was still observed and all seven states used the same tactics resulting in a series of stalemates since, whenever one engaged with another in battle, neither could gain an advantage. In time, this repetition of seemingly endless, and completely futile, warfare became simply the way of life for the people of China during the era now referred to as the Warring States Period. The famous work The Art of War by Sun-Tzu (l. c. 500 BCE) was written during this time, recording precepts and tactics one could use to gain advantage over an opponent, win the war, and establish peace.

Sun Tzu was a Chinese general, military strategist, writer, and philosopher who lived in the Eastern Zhou period of ancient China. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of The Art of War, an influential work of military strategy that has affected both Western and East Asian philosophy and military thinking. His works focus much more on alternatives to battle, such as stratagem, delay, the use of spies and alternatives to war itself, the making and keeping of alliances, the uses of deceit, and a willingness to submit, at least temporarily, to more powerful foes. Sun Tzu is revered in Chinese and East Asian culture as a legendary historical and military figure. His birth name was Sun Wu and he was known outside of his family by his courtesy name Changqing The name Sun Tzu by which he is more popularly known is an honorific which means "Master Sun".

Sun Tzu's historicity is uncertain. The Han dynasty historian Sima Qian and other traditional Chinese historians placed him as a minister to King Helü of Wu and dated his lifetime to 544–496 BC. Modern scholars accepting his historicity place the extant text of The Art of War in the later Warring States period based on its style of composition and its descriptions of warfare. Traditional accounts state that the general's descendant Sun Bin wrote a treatise on military tactics, also titled The Art of War. Since Sun Wu and Sun Bin were referred to as Sun Tzu in classical Chinese texts, some historians believed them identical, prior to the rediscovery of Sun Bin's treatise in 1972.

Sun Tzu's work has been praised and employed in East Asian warfare since its composition. During the twentieth century, The Art of War grew in popularity and saw practical use in Western society as well. It continues to influence many competitive endeavours in the world, including culture, politics, business and sports.

The ancient Chinese people worshipped the bronze and iron swords, where they reached a point of magic and myth, regarding the swords as “ancient holy items”. Because they were easy to carry, elegant to wear and quick to use, bronze swords were considered a status symbol and an honour for kings, emperors, scholars, chivalrous experts, merchants, as well as common people during ancient dynasties. For example, Confucius claimed himself to be a knight, not a scholar, and carried a sword when he went out. The most famous ancient bronze sword is called the “Sword of Gou Jian”.

This is one of a stunning collection of original archaic bronze age weaponry we have just acquired and has now arrived. Many are near identical to other similar examples held in the Metropolitan in New York, the British royal collection, and such as the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, China.

A complimentary display stand, will be included.

As with all our items, every piece is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. read more

2595.00 GBP

21st Regiment Essex Fusiliers Large Service Helmet Flaming Grenade Badge. Circa.1887

Canadian Militia busby helmet badge. 21st Regiment Essex Fusiliers Fur Busby grenade. Circa.1887 Brass grenade with two lugs to the reverse in excellent condition.

A military presence in Windsor and Essex County dates back as far as 1701, when all men in the community were essentially militia members, armed to combat a perceived 'Indian threat'. When Irish-American Nationalists invaded Canada in 1866, even stronger forces were established locally. By 1885, local militias had amalgamated into the 21st Essex Battalion of Infantry.

By the advent of the First World War, the 21st Battalion (now known as the 21st Regiment Essex Fusiliers) was placed on active service. Initially, they contributed to Canada's 1st Battalion, upon its formation in 1914, then later the 18th Battalion (consisting largely of Essex Fusilier soldiers. The 18th Battalion served in France and Flanders from 1915 until the Armistice.

The regiment perpetuated the 18th (Western Ontario) Battalion, 99th (Essex) Battalion and 241st (Canadian Scottish Borderers) Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force and held its final Order of Precedence as 40. Battle honours for the regiment include: First World War: Ypres 1915 & 17, Festubert 1915, Mount Sorrel, Somme 1916 & 18, Flers-Courcelette, Thiepval, Ancre Heights, Arras 1917 & 18, Vimy 1917, Hill 70, Passchendaele, Amiens, Scarpe 1918, Hindenburg Line, Canal du Nord, Cambrai 1918, Pursuit to Mons, France & Flanders 1915-18 Second World War: Dieppe Raid (1942), Battle of Verrigres Ridge (1944), liberation of Dieppe (1944), Battle of the Scheldt (1944), The Rhine (1944-1945), Northwestern Europe

By 1926, an alliance was formed with the Essex Regiment of the British Army, and by 1927, the Essex Scottish had adopted the MacGregor tartan based on Scottish Highland tradition. That year an alliance was also established with the Queen’s Own Royal West Kent Regiment of the British Army.

The Regiment was the first unit of men in Western Ontario to be called up during World War II and one of the first Canadian units to see battle overseas. Their first fight was the tragic Dieppe raid on August 19th, 1942 where the Regiment was hit particularly hard during Operation Jubilee. When the smoke cleared, the Regiment had lost 121, and many of the survivors were either wounded or captured. With barely enough time to regroup, the regiment prepared itself for the invasion of France. On July 5th 1944, it participated in the bloody landing at Normandy, and then fought on through France, Holland and Germany until the war's end.

By then, the regiment had suffered 552 dead and had been inflicted with the highest number of casualties of any unit in the Canadian Army-a staggering 2,510. read more

245.00 GBP

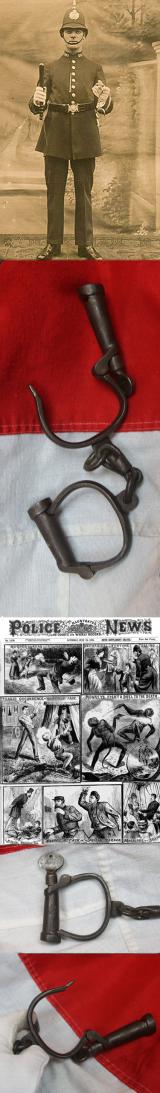

Victorian Police 'Jack the Ripper' Era Type Handcuffs or 'Derby's' & Original Oval Flat Key

Good flattened head key type, with board of ordnance broad arrow stamp and serial number.

The type as was made and first used in the early Victorian era from the very beginnings of the British Police service, and on well into the next century. Excellent working order early flat key type. A good and fine condition pair of original 'Derby' cuffs used by the 'Bobbies' or 'Peelers', with the traditional rotating spiral key action.

They are also the very type that were used, and as can be seen, in all the old films of the Whitechapel Murders, and Sherlock Holmes' adventures in the gloomy London Fog.

Originally handcuffs were made of a large wooden toggle with a loop of cord, which was slipped over a prisoner’s wrists and twisted. Manufacturers Hiatt and Company, founded in Birmingham in 1780, developed a new patent for restraints, which became standard issue when the Metropolitan Police was created in 1829.

In 1818 Thomas Griffin Hiatt appears in the Wrightson Directory for the first time as a manufacturer of felon's irons and gate locks, located on Moor St. in Birmingham. Some time in the next few years Hiatt moved around the corner to 26 Masshouse Lane, where he is located in the next edition of the Wrightson's Birmingham directory as a manufacturer of felon's irons, gate lock, handcuffs, horse and dog collars. The Hiatt Company remained at the 26 Masshouse Lane address until the premises were destroyed by the World War II German bombing in 1941.

The Whitechapel murders were committed in or near the largely impoverished Whitechapel district in the East End of London between 3 April 1888 and 13 February 1891. At various points some or all of these eleven unsolved murders of women have been ascribed to the notorious unidentified serial killer known as Jack the Ripper.

The murderer or murderers were never identified and the cases remain unsolved. Sensational reportage and the mystery surrounding the identity of the killer or killers fed the development of the character "Jack the Ripper", who was blamed for all or most of the murders. Hundreds of books and articles discuss the Whitechapel murders, and they feature in novels, short stories, comic books, television shows, and films of multiple genres.

The poor of the East End had long been ignored by affluent society, but the nature of the Whitechapel murders and of the victims' impoverished lifestyles drew national attention to their living conditions. The murders galvanised public opinion against the overcrowded, unsanitary slums of the East End, and led to demands for reform. On 24 September 1888, George Bernard Shaw commented sarcastically on the media's sudden concern with social justice in a letter to The Star newspaper: read more

220.00 GBP

We Have New Fascinating Items Added To The Site Every Single Day.

Wonderful and intriguing pieces, such as a Renaissance period helmet and fusetto stiletto dagger, as used by a chief Cannoneer of the Papal Army in the 16th century, up to 500 years ago, commanded by Cesare Borgia, son of the Borgia Pope, and later in the 16th century, By Matteo Barbarini, brother to Pope Urban VIIIth.

Also, many military souvenirs of all kinds from WW1 and WW2, to, say, a Spanish Conquistador's helmet of the 16th century, to Ian Fleming’s James Bond, 1960's Ist Edition books, a Baker Rifle sword-bayonet, to original samurai swords hundreds of years old.

All are original, beautiful, historical and truly intriguing pieces.

This week we will be adding some superb and inexpensive Roman and Greek antiquities, plus medieval antiquities too. We are also sending our deliveries to our clients in the UK, Australia, America, & Canada, every working day, containing the rarest and finest pieces, from books, to helmets, swords and antiquities. read more

Price

on

Request

Princess Victoria's (Royal Irish Fusiliers) OR's fur cap grenade circa 1890

Die-stamped brass, the ball bearing Eagle on a tablet inscribed '8'.

The Eagle and '8' represents the flagstaff eagle of the 8th French Light Infantry captured by Sgt Patrick Masterson of the 87th Fusiliers at Barossa on 5th March 1811. It is 3.75 inches long. The French Imperial Eagle was the emblem of the Grande Armee of Napoleon I, and during the Peninsular War of 1808-1814 and the Battle of Waterloo, the capture of an eagle by enemy troops was a massive blow to any regiment.

In the instance of the Battle of Barrosa, in 1811, the British captured their first ever eagle. The captor was an Irish Sergeant of the 87th (Royal Irish Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot. Looking at the history of the battle read more

110.00 GBP

A Grenadier Guards Officer's Sword From The Lanes Armoury Sold, and Raised £2,465 For The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham Charity, Photographed With H.M. King Charles formerly HRH P.O.W

Swords, over the eons, have been part of the journey of civilised mankind since the days of pre-history, before 1200 bc. And over 3200 years later, even ‘retired’ historic swords can be put to a fine use that they were certainly not entirely designed to perform.

We were absolutely delighted that a sword, from us, once sold at their special charity ball auction. The auction raised in total, £56,000, a most handsome sum.

Mike Hammond, the Chief Executive, wrote to us to say;

"We’ve already had hundreds more of people staying at the house since we opened our doors to military patients and their families, and the sword has helped in funding another 99 days of accommodation for the families".

The Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Birmingham is home to the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, which treats UK military patients injured or wounded anywhere around the world.

The hospital charity built Fisher House, a home away from home for military patients and their families to stay whilst they are having medical treatment. You can see more about Fisher House at their website www.fisherhouseuk.org All donations will be most gratefully received.

A photo in the gallery is of HM King Charles when as HRH Prince Charles, opening Fisher House. read more

Price

on

Request

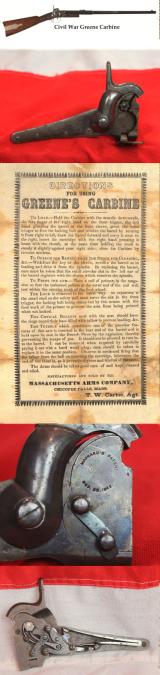

A Superb Case Hardened Steel Gun Lock Of a Greene Carbine 1856 For the Crimean War Then the American Civil War

Scarce British-Type Greene Carbine by Massachusetts Arms Company

Case-hardened swivel breech action with Maynard tape primer system. Lock marked: Queen's crown /VR/Mass.Arms Co./U.S.A./1856.

James Durell Greene was a prolific firearms inventor and determined to make his mark This carbine lock was manufactured by the Massachusetts Arms Company and exported to Great Britain after being inspected and stamped with the Queen's Crown by British inspectors in the USA. These were used by the British Cavalry in the Crimean War but re-exported to the USA after the Crimea War. These fine guns were deemed to be very accurate but the paper and linen cartridges of the time were criticised as being prone to swell in the damp and consequently the carbine did not find favour with the British Government. The carbine features an unusual "floating thimble" to obdurate the breech and an internal "pricker" that punctured the cartridge. It also featured Maynard Tape priming which was in the forefront of priming technology at the time and the mechanism for this is in perfect condition. The quality of workmanship is exceptional and it actions as crisply today as it did when it was made 158 years ago.

An exceptional item in outstanding condition. Only 2000 were manufactured and a complete carbine sold at Rock Island auction for $6,900 in 2021 read more

395.00 GBP

A Very Good & Highly Desirable, 19th Century Pistol Powder Flask For Cased Duellers or Revolver

The most desirable kind of antique powder flask. The large fowling piece flasks can be very inexpensive, but the small 'cased pistol' sized flasks are incredibly sought after, as they can fit into cases were the flask is missing beautifully and complete a cased set perfectly..

A very good flask with crescent and bush embossed design, good spring and nice patination. All good seams. A great find for those that have a cased revolver single or pair or a pair of cased duellers lacking their flask. We show several cased pistols all with similar sized pistol flasks, including a cased pair of Colt pocket revolvers, and a pair of Durs Egg duellers.The flask is 4.75 inches long overall, max width 2 inches. read more

295.00 GBP