Antique Arms & Militaria

A Beautiful, Impressed Twin Head Profile Roman Oil lamp 1st to 2nd Century, Imperial Roman Province Period. From the Time of Pontus Pilate & King Herod, to The Eruptions of Pompeii

Clay with impressed twin busts of bearded men back to back. Footed base. Oil lamps are ubiquitous at archaeological sites across the Mediterranean region. They were a crucial part of life in many cultures. Practically speaking, they were a source of portable artificial light, much like a candle or modern torch or flashlight. They were also important in sacred settings. They were frequently used in ceremonies, given as votive offerings, or placed in burial chambers. Age of the Roman Emperors

Augustus’ rule restored morale in Rome after a century of discord and corruption and ushered in the famous pax Romana–two full centuries of peace and prosperity. He instituted various social reforms, won numerous military victories and allowed Roman literature, art, architecture and religion to flourish. Augustus ruled for 56 years, supported by his great army and by a growing cult of devotion to the emperor. When he died, the Senate elevated Augustus to the status of a god, beginning a long-running tradition of deification for popular emperors.

Augustus’ dynasty included the unpopular Tiberius (14-37 A.D.), the bloodthirsty and unstable Caligula (37-41) and Claudius (41-54), who was best remembered for his army’s conquest of Britain. The line ended with Nero (54-68), whose excesses drained the Roman treasury and led to his downfall and eventual suicide. Four emperors took the throne in the tumultuous year after Nero’s death; the fourth, Vespasian (69-79), and his successors, Titus and Domitian, were known as the Flavians; they attempted to temper the excesses of the Roman court, restore Senate authority and promote public welfare. Titus (79-81) earned his people’s devotion with his handling of recovery efforts after the infamous eruption of Vesuvius, which destroyed the towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii.

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land. read more

475.00 GBP

Archaic Zhou Dynasty Bronze Halberd or ‘Ge’ Circa 5th Century BC the Period of the Great Military Doctrine 'The Art of War' by General Sun-Tzu

From a collection of ancient Chinese weapons we recently acquired including three 'Ge'. This is the very type of original ancient ceremonial halbard, defined by the ancient Chinese as a dagger axe 'Ge' and exactly the type as used by the warriors serving under the world renowned General Sun Tzu, in the Kingdom of Wu, who is thought by many to be the finest general, philosopher and military tactician who ever lived. His 2500 year old book on the methods of warfare, tactics and psychology are still taught and highly revered in practically every officer training college throughout the world.

In excavated condition, cast in one piece, slightly curved terminal blade of flattened-diamond section, pierced along a basal flange with three slots, and a hole with fabulous areas of crystallized malachite, blue/green patina.

We also show in the gallery a schematic of how this 'Ge' halbard would have been mounted 2500 odd years ago on its long haft, and used by a charioteer warrior, there is also one depicted being carried in a painting that we show in the gallery being used in a chariot charge in the Zhou dynasty.

This is a superb original ancient piece from one of the great eras of Chinese history, it is unsigned but near identical to another that was signed and inscribed with details that have now been fully translated, deciphered and a few years ago shown at Sothebys New York estimated to a sale value of $300,000. Its research details are fully listed below, and it is photographed within our gallery for the viewers comparison. Naturally, our un-inscribed, but still, very rare original version, from the same era and place, is a much more affordable fraction of this price

The signed and named Sotheby's of New York example that we show in the gallery, was formerly made for its original warrior owner, Qu Shutuo of Chu, it is from the same period and in similar condition as ours. We reference it's description below, and it is photographed within the gallery, it is finely cast with the elongated yuan divided by a raised ridge in the middle of each side and extending downward to form the hu, inscribed to one side with eight characters reading Chu Qu Shutuo, Qu X zhisun, all bordered by sharply finished edges, the end pierced with three vertically arranged chuan (apertures), the nei with a further rectangular chuan and decorated with hook motifs, inscribed to one side with seven characters reading Chuwang zhi yuanyou, wang zhong, and the other side with five characters reading yu fou zhi X sheng, the surface patinated to a dark silver tone with light malachite encrustation

An Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Ritual Bronzes. Loaned by C.T. Loo & Co., The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, 1940, pl. XXXIII.

New Orleans Museum of Art, New Orleans, March - June 1948.

This inscribed bronze halberd blade, although typical in form, is uniquely important as its inscription serves as a critical primary source that reveals the name of its original owner: Qu Shutuo of Chu. The only known close counterpart to this blade is a damaged bronze halberd blade, missing the yuan, and inscribed on the hu with seven characters, which can be generally translated to ‘for the auspicious use of Qu Shutuo of Chu’. That halberd is now in the collection of the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, and published in Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng Compendium of inscriptions and images of bronzes from Shang and Zhou dynasties, vol. 32, Shanghai, 2012, no. 17048

The remaining thirteen inscriptions can be translated as: 'Qu Shutuo of Chu, Qu X's grandson, yuanyou of the King of Chu'. Based on the inscription, the owner of this blade can be identified as such.

See for reference; The Junkunc Collection: Arts of Ancient China / Sotheby's New York

Lot 111

We also show in the gallery a photo of another similar halberd from a museum exhibition, of a Chinese ancient king bodyguard’s halberd gilt pole mounts for his personal charioteer

This is one of a stunning collection of original archaic bronze age weaponry we have just acquired. Many are near identical to other similar examples held in the Metropolitan in New York, the British royal collection, and such as the Hunan Provincial Museum, Hunan, China. As with all our items, every piece is accompanied by a certificate of authenticity. Approx 8.5 inches across.

read more

1895.00 GBP

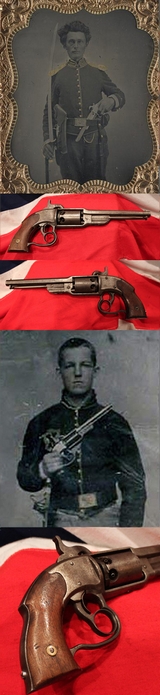

A Most Scarce and Superb US Civil War, Savage North, Navy .36cal Revolver With Hand Carved “Trophy Cuts’. Most Likely Created By the Original Combatant, Issued to Either the Wisconsin, Missouri or Kansas Cavalry Regiments

A rare revolver that we are lucky to find only one or two a year, and this one is a particularly nice example.

During the Civil War the savage revolvers were acquired by 'Witcher’s Nighthawks', & 'White’s Rebels', two Confederate cavalry regiments in Virginia, the 11th Texas Cavalry under Col. George Reeves, and the Union’s US Navy’s warships.

The Savage was probably The most unusual and distinctive revolver ever made, and certainly the most distinctive revolver used during the American Civil War in the 1860s. Nothing was ever made before quite like it frankly since it has very modern features which were revolutionary at the time and utilised by just a few revolvers many decades. With four distinctive down stroke cuts and two cross cuts to the butt stock. This by tradition is recognised as trophy marks. One cut for each successful gunfight outcome. Produced in the 1860's. Standard three line address and patent markings on top of the frame above the cylinder. Henry North patent action, with a ring trigger for revolving the cylinder and cocking the hammer, and a second conventional trigger for firing, and a shared heart-shaped trigger guard. Very good fully operational action. Two-section cylinder, with the front section unfluted and the rear section fitted to the frame with cut-outs along the sides. Smooth grips with a distinctive blackstrap profile.

One of the very scarce revolvers of the US Civil War. With good clear maker and patent markings. A very collectable pistol that were made in far fewer numbers than their sister guns, the Colt and the Remington. A very expensive gun in it's day, it had a complex twin trigger mechanism, and a revolving cylinder with a spring operated gas seal. One of our very favourite guns of the 19th century, that epitomises the extraordinary and revolutionary designs and forms of arms that were being invented at that time, and for it's sheer extravagance of complexity, combined with it's unique and highly distinctive profile.

The Savage Navy Model, a six shot .36 calibre revolver, was made only from 1861 until 1862 with a total production of only 20,000 guns. This unique military revolver was one of the few handguns that was produced only for Civil War use. Its design was based on the antebellum Savage-North "figure eight" revolver, the Savage Navy had a unique way of cocking the hammer. The shooter used his middle finger to draw back the "figure 8" lever and then pushed it forward to cock the hammer and rotate the cylinder. The Union purchased just under 12,000 of these initially at $19.00 apiece for use by its cavalry units. Savage Navy revolvers were issued to the 1st and 2nd Wisconsin U.S. Volunteer Cavalry regiments, and 5th Kansas Volunteer Cavalry while the State of Missouri issued 292 Savage revolvers to its Missouri Enrolled Militia units. The remaining revolvers were purchased by private means and shipped to the Confederacy for use with the 34th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry (Witcher's Nighthawks), the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry (White's Rebels), 11th Texas Cavalry, 7th Virginia Cavalry (Ashby's Cavalry), and 7th Missouri Cavalry. The United States Navy also made a small purchase of 800 Savages during 1861 for use on its ships. One of our very favourite guns of the 19th century, that epitomises the extraordinary and revolutionary Heath Robinsonseque designs and forms of arms, that were being invented at that time, and for it's sheer extravagance of complexity, combined with it's unique and highly distinctive profile.

We show in the gallery three different original photos of Civil War soldiers, each one proudly carries his Savage revolver for information only, not included. In May 2018 a similar Savage Navy Revolver sold in auction in America for $48,875, naturally it was a very nice example.

As with all our antique guns no license is required as they are all unrestricted antique collectables read more

3150.00 GBP

A Former Helmet Created From a Helmet in the Royal Collection. A Victorian, Italian Morion Helmet, Probably From Milan, Circa 1544. Likely Created by Instruction From The Curators Of the Royal Collection In Around 1873

This is likely a unique copy made in the 19th century directly from a fabulous helmet in the Royal Collection, in the Round Tower at Windsor Castle, and believed to be from the personal collection of King George IIIrd. Naturally as the original would never become available this is a unique opportunity to own a simulacrum from Her Majesty’s armoury. This stunning helmet was made in the 19th century using the incredibly advanced copper electrotype system with fully faithful and exact detail from the royal helmet. A system so exact in its ability to recreate an identical version of the original, it was considered by some to be a magical marvel. It has a slightly misshapen damage at the comb. The plume holder etched with a religious scene (possibly the Trinity) and the inscription LAVDAMVS TE (We praise Thee) . In the Round Tower at Windsor Castle in 1904. The collection of George III included ‘A Helmet English, Very Ancient Made of Iron – Embossed with Scrolls – Stars and Leaves had formerly been Gilt’, which was sent to the armoury from Buckingham House on 20 September 1821.

Item no. 2048 in the North Corridor Inventory, which records the arrangement of the Collection at Windsor Castle. We believe it was most likely made by instruction from the curators of the Royal Collection, that commissioned a identical copy made, possibly for the national museum collection, such as the amazing plaster copies of unique worldwide masterpieces in the V&A. Opened in 1873, the Cast Courts display copies of some of the world's most significant works of art reproduced in plaster, electrotype, photography, and digital media. The cast collection is famous for including reproductions of Michelangelo's David, Trajan's Column, and Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise, amongst many others. Electrotyping was an incredible chemical method for forming metal parts that exactly reproduce a model. The method was invented by Moritz von Jacobi in Russia in 1838, and was immediately adopted for applications in printing and several other fields. As described in a treatise, electrotyping produces "an exact facsimile of any object having an irregular surface, whether it be an engraved steel- or copper-plate, a wood-cut, or a form of set-up type, to be used for printing; or a medal, medallion, statue, bust, or even a natural object, for art purposes." In art, several important "bronze" sculptures created in the 19th century are actually electrotyped copper, and not bronze at all One of the earliest documented large-scale (1.67 metres (5.5 ft)) electrotype sculptures was John Evan Thomas's Death of Tewdric Mawr, King of Gwent (1849). The electrotype was done by Elkington, Mason, & Co. for the Great Exhibition of 1851. Link to see the original example http://www.royalcollection.org.uk. The gallery shows a photo of the original Italian morion still in the Royal Collection, but made in iron, however, it was originally fully gilded, which this copy still appears to be, likely in order to show how it once looked when it was originally made in around 1544 in Italy. It is not often any collector has the opportunity to purchase an absolute identical version of a piece of armour in the Royal Collection that was actually made from the Royal original. If the original were to ever come on the open market which it never will of course it would likely be worth six figures or even seven figures 1 million pounds plus due to its Royal connection.

Probably the most famous electrotype simulacrum seen today is the Wimbledon Women’s final trophy. See photo 8 in our gallery.

Tennis fame

The version held aloft as the Wimbledon Ladies Singles Championship trophy was made in silver by the firm of Elkington and Company of Birmingham in 1864. This version is known as the Venus Rosewater Basin, and was first presented at Wimbledon in 1886. Every champion since has had her name engraved on it. The reproduction of the basin was made by the electrical deposition of silver into a mould, and used the plaster cast of an Enderlein basin in the Louvre as a model. When it was first created, the Wimbledon reproduction represented the height of 19th century modernity and was at the forefront of technological innovation. The V&A has an electrotype version which was also made by Elkington, and was moulded from the same plaster cast, 12 years before the creation of the Wimbledon trophy. read more

1995.00 GBP

A Most Fine, Antique, Original Regimental Embroidery Of the Royal Artillery, P Battery, 63rd Royal Field Artillery, With Crimean War, Canada and Boer War Battle Honours. One Of The Best Examples We Have Seen in 50 Years

Stunningly handsome embroidered regimental wreathed crest, with the field cannon and motto ‘Ubique’ of legendary ‘P’ Battery, and also bearing their later title the 63rd RFA. Royal Field Artillery

Likely stiched by an officer's lady from the regiment. A traditional pastime of the wives of the serving or past serving men from British Regiments in the army, or, by sailors themselves in the Royal Navy was the making of highly intricate embroidery of their regimental colours.

From the doomed attempt to seize the Russian guns by the Light Brigade at Balaclava, to the Siege of Sebastopol itself, artillery played a major part in the Crimean War. The official history of the Royal Artillery Regiment in the conflict is therefore indispensible to a full picture of the war. Original embroidery , made in the Victorian to WW1 period, nicely framed. With Crimean War, Canada and Boer War Battle Honours. The story of the 63rd RFA from 1899; The 63rd lost their guns on the Ismore. They were refitted and joined Buller in Natal in time to take part in the operations about Spion Kop and Vaal Krantz and in the final relief actions. One officer was mentioned in General Buller's despatch of 30th March 1900. The battery accompanied that general in his northward movement to the south of the Transvaal, and a section went with General Clery to Heidelberg. In General Buller's final despatch 2 officers were mentioned. Towards the close of 1900 and in 1901 the battery was employed about the Standerton line, and four guns accompanied the column of Colonel Colville which operated on that line and in the north-east of the Orange River Colony. Referring to an action near Vlakfontein, Lord Kitchener in his telegram of 22nd December 1900 said, "Colonel Colville attributes the small loss to the excellent shooting of the 63rd Battery and the skilful leading of Lieutenant Jarvis, 13th Hussars, and Captain Talbot and Lieutenant White of the Rifle Brigade". 34.5 inches x 29 inches in the frame. read more

650.00 GBP

A Gold Inlaid Traditional Persian Armour Suite, of Helmet, Shield & Arm Defence. The Kulah Khud,(کلاهخود) Sipar (سپر), and Bazu Band (بازوبند). Late 18th to Early 19th Century, Possibly Wootz Steel { Pulad}

A simply stunning suite of original armour comprising the traditional Kulah khud, dhal, and bazu band. Most likely made in Isfahan

A very fine set of Persian armour consisting of a shield; sipar (سپر), helmet; kulah khud (کلاهخود) and armguard; bazu band (بازوبند) for the left hand. Such sets often come with only one bazu band, and curiously, it is always the left one like seen here.

The helmet has a hemi-spherical skull, pierced with four heart-shaped panels each fitted with an iron plate within a moulded frame, the skull fitted at its apex with a low spike, a pair of plume-holders at the front and with a staple for a sliding optional nasal guard, decorated over the greater part of its surface with gold koftgari flowers and foliage and mail neck-defence of butted links; the bazu band of a gutter-shaped form, fitted with hinged inner arm-defence, each decorated with gold and silver koftgari foliage, and chain mail covering for the hand of butted links, and with a padded lining; and the dhal somewhat in the size of a buckler of shallow convex form, the outer face applied with brass and gold and silver koftgari inlay foliage and flowers and decorated with silver koftgari foliage enriched with gold flowers: Koftgari is the name for Indian form of Damascening used on Indo-Persian armour and weaponry, which also closely resembles the Damascening found in Persia and Syria.

The inlay process begins after the piece is moulded and fully formed. The intended design is engraved into the base metal and fine gold or silver wire is then hammered into the grooves.

The base metal is always a hard metal, either steel, iron or bronze, and the inlay a soft metal, either gold or silver. This combination prevents the base from deforming when the wire inlay is hammered into the surface and results in the inlaid areas being well defined and of sharp appearance.

Swords, shield and armour were often decorated in koftgari . Persian arms and armor enjoyed widespread fame across the world and naturally found their way to the armories of Ottoman and Indian rulers. Aside from fine craftsmanship, the Persians were known to produce very fine wootz, most notably in the city of Isfahan.

Armours such as this fine suite could be used by the guard of nobility or Ta'zieh

The Ta'zieh were religious passion plays that recounted the tragedy of Hussein, the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad. They were performed at set dates and local royalty, and even the Shah himself, took great pride in organizing them in the most lavish manner:

"Among the " properties " may be reckoned horses, mules, camels, etc, all richly caparisoned; lions and other wild beasts from the Shah's menagerie; carpets, shawls, dresses, and suits of armour of every description; European uniforms for the Feringhi ambassador and his suite, who intercede with Yezid for the lives of Hussein's family; and an endless variety of ornamental objects old and new. Some months ago the Shah ordered a collection of ancient metal vases to be made, to add to the splendour of the next Tazieh."

-Robert Murdoch Smith, 1876

Fine sets of Persian arms and armour thus found their way through export to the palaces of Ottoman and Indian rulers but also to the arms panoplies that were commonly found in the homes of European gentlemen, particularly in Britain. The British traditionally always had a great fondness of this form of high quality, exotic Asian weaponry, helmetry and armour. read more

6950.00 GBP

A Superbly Attractive Native American Trade Style Tomahawk Axe, Typical Import Pattern With Trader’s Inventory Stamp. Reservation Period

With studded wooden haft, the axe with single curved blade and rounded opposing pole hammer. Probably 19th century or later. The metal trade tomahawk has long been an object of fascination for both the amateur collector and the ethnologist. Few other implements have ever combined so many different

functions: tool, weapon, sceptre, symbol and smoking pipe. In this one instrument is collected the lore of handicraft, warfare, prestige, ceremony and personal comfort. Captain John Smith is beheved to have been the first to bring the word into English in his brief vocabulary of Indian terms prepared sometime during the years 1607-1609, when he defined tomahaks simply as meaning "axes." Later he added that the term was applied to both the native war club and the imported iron trade hatchet. Almost from the moment the Native American Indian first saw the metal hatchet or tomahawk, likely made in Sheffield, England, he coveted it, and sought to possess one for himself. The efficiency of the new implement was readily apparent : it was deadlier in combat, more efficient in cutting wood, and just as useful as a ceremonial object. Although it was an excellent weapon, the new American man was not as reluctant to trade it as he was to dispense guns. The axe was also self-sufficient; it could function without such components as powder and ball that had to be obtained from the traders. Thus the hatchet could and did spread rapidly through Indian trade routes far from the points of frontiersman’s contact, reaching tribes and areas as yet unknown to the few Europeans along the coast. The first contact of the Indian with the iron or steel axe undoubtedly occurred with the arrival of the Vikings, and to judge from accounts in the sagas, the meetings were not auspicious. Two instances are recounted which may well be the first recorded encounters of the Indian with the weapon which later was to become almost synonymous with his warfare. The Saga of Eric the Red recalls the first reported battle of the Vikings with the natives of America

“The Skrellings Indians, moreover, found a dead man, and an axe lay beside him. One of their number picked up the axe and struck at a tree with it, and one after another they tested it and it seemed to them to be a treasure, and to cut well; then one of their number seized it, and hewed at a stone with it so that the axe broke, whereat they concluded that it could be of no use, since it would not withstand stone, and they cast it away.”

But not all Indians thought the same.

The potentialities of the axe as a weapon were apparent to the Indian from the outset. Garcilaso de la Vega tells of a bloody fight between an Indian armed with a captured battle axe and several of De Soto's soldiers, in which he even includes a i6th century version of the old story of a man being cut in two so quickly by a keen blade that he remains standing and has time to pronounce a benediction before falling. In Florida, Jacques LeMoyne illustrated the murder of a colonist by an Indian with an axe during the brief French settlement at Fort Caroline, 1564-1565. By the early 17 th century the tomahawk was firmly established in the minds of the white settlers as the Indians' primary weapon, and was much more feared than the bow and arrow. Even after the Indians had obtained a sizeable number of firearms, the tomahawk retained its popularity and importance. Once a gun had been fired, it was useless until it could be reloaded ; an edged weapon was needed as a supplement, and this was the tomahawk. Moreover, for surprise attacks and raids, a firearm was frequently out of the question. This axe’s trade stamp could be a weight mark, or even a quantity mark. Lists of trade goods and treaty gifts indicate that the axe, hatchet, or tomahawk were among the most desired objects. As many as a quantity of 300 axes might be handed out at one treaty meeting, and Sir Wilham Johnson estimated that the Northern Indian Department needed 10,000 axes for trade purposes in the year 1765 alone. This is a 19th century trade axe.

Head 7.5 inches, x 3.25 inches length 20.5 inches. We cannot ship this item to the US. read more

975.00 GBP

An Original, Antique, Edwardian Royal Artillery Undress Pouch and Bullion Dress Cross Belt

Gold bullion crossbelt with gilt bronze fitting of traditional finest quality. A leather undress pouch with gilt brass swivel mounts. Reverse of leather pouch with old score marks. The undress pouch is in patent leather with gilt Royal Artillery badge and motto. The belt has superb original bullion with gilt bronze mounts, embellished finely cast acanthus leaves and the flaming canon ball. The design of the full dress pouch followed that of the full dress sabretache in that the royal arms were central over the battle honour, UBIQUE, latin for 'everywhere'. Laurel leaves are on the left and oak leaves on the right. Below UBIQUE is a metal gun badge, and below that is a three part scroll with the regimental motto QUO FAS ET GLORIA DUCUNT - Where Right and Glory Lead. This pouch was worn for special occasions. Mostly the full dress pouch belt was worn with the undress black leather pouch. A vintage photo in the gallery show a Royal Artillery officer wearing his cross belt and pouches however, the pouches are worn across the back and not visible from the front in this photo read more

595.00 GBP

An Original Ancient Medieval 13th Century, Knight's, Iron Battle Mace & Scorpion Flail MaceHead

A pineapple shaped iron head, with large centre mounting hole, for a leaded chain or a haft. The wooden haft as usual has rotted away, but could be replaced one day for display purposes. This is the type of War Mace that were also used as a Flail Mace, with the centre mount being filled with lead and a foot to a foot and a half long chain mounted within in, and then it was attached to a wooden haft, so it could be flailed around the head. Flattened pyramidical protuberances, most possibly English. Made for a mounted Knight to use as an Armour and Helmet Crusher in mortal combat. It would have been continually used up to the 15th to even 16th century. On a Flail it had the name of a Scorpion in England or France, or sometimes a Battle-Whip. It was also wryly known as a 'Holy Water Sprinkler'. King John The Ist of Bohemia used exactly such a weapon at the Battle of Crecy, for as he was blind, and the act of 'Flailing the Mace' meant that his lack of site was no huge disadvantage in close combat. Although blind he was a valiant and the bravest of the Warrior Kings, who perished at the Battle of Crecy against the English in 1346. On the day he was slain he instructed his Knights both friends and companions to lead him to the very centre of battle, so he may strike at least one blow against his enemies. His Knights tied their horses to his, so the King would not be separated from them in the press, and they rode together into the thick of battle, where King John managed to strike not one but at least four noble blows. The following day of the battle, the horses and the fallen knights were found all about the body of their most noble King, all still tied to his steed. It was his personal banner of the triple feathers that was adopted following this battle by the Prince of Wales as his standard, and still used by Prince William the current Prince of Wales today.

During the Middle Ages metal armour such as mail protected against the blows of edged weapons. Solid metal maces and war hammers proved able to inflict damage on well armoured knights, as the force of a blow from a mace is great enough to cause damage without penetrating the armour. Though iron became increasingly common, copper and bronze were also used, especially in iron-deficient areas.

It is popularly believed that maces were employed by the clergy in warfare to avoid shedding blood (sine effusione sanguinis). The evidence for this is sparse and appears to derive almost entirely from the depiction of Bishop Odo of Bayeux wielding a club-like mace at the Battle of Hastings in the Bayeux Tapestry, the idea being that he did so to avoid either shedding blood or bearing the arms of war. One of the Crusades this type of mace may have been used was the Crusade of 1239, which was in territorial terms the most successful crusade since the First. Called by Pope Gregory IX, the Barons' Crusade broadly spanned from 1234-1241 and embodied the highest point of papal endeavour "to make crusading a universal Christian undertaking." Gregory called for a crusade in France, England, and Hungary with different degrees of success. Although the crusaders did not achieve any glorious military victories, they used diplomacy to successfully play the two warring factions of the Muslim Ayyubid dynasty (As-Salih Ismail in Damascus and As-Salih Ayyub in Egypt) against one another for even more concessions than Frederick II gained during the more well-known Sixth Crusade. For a few years, the Barons' Crusade returned the Kingdom of Jerusalem to its largest size since 1187.

This crusade to the Holy Land is sometimes discussed as two separate crusades: that of King Theobald I of Navarre, which began in 1239; and, the separate host of crusaders under the leadership of Richard of Cornwall, which arrived after Theobald departed in 1240. Additionally, the Barons' Crusade is often described in tandem with Baldwin of Courtenay's concurrent trip to Constantinople and capture of Tzurulum with a separate, smaller force of crusaders. This is because Gregory IX briefly attempted to redirect the target his new crusade from liberating the Holy Land from Muslims to protecting the Latin Empire of Constantinople from heretical Christians. read more

985.00 GBP

A Fabulous & Massive Antique Moro Keris Kalis, A Phillipines Pre Colonial Style Warrior's Sword

A kalis ( in Jawi script: كاليس ) is a type of Philippine sword. The kalis has a double-edged blade, which is commonly straight from the tip but can be wavy near the handle. Kalis exists in several variants, either with a fully straight or fully wavy blade. It is similar to the Javanese keris, but differs in that the kalis is a sword, not a dagger. It is much larger than the keris and has a straight or slightly curved hilt, making it a primarily heavy slashing weapon (in contrast to the stabbing pistol grip of the keris).

Blade length (incl. gangya): 58.5 cm (23 in.)

Width of blade (mid-point): 4 cm

Hilt length: 10.2 cm

OAL: 71 cm (27 7/8 in.)

Width of gangya {guard} tip to tip: 13.2 cm

This blade is of laminated construction. The ricikin shows a secah kasang (elephant trunk), gandhik, praen (tusk), and lambe gajah (elephant lips). The orientation of these features is similar to the much later forms of Indonesian Keris, although the lambe gajah straddle the line of separation between the gandhik and the gangya, instead of appearing low on the gandhik. There is no sogokan or blumbanggan. Greneng and jenggot are present, and both show wear. There is a single, one-piece, asang asang. The hilt is a single piece of carved banati wood, topped with cushion shaped pommel. The grip is bound with criss-crossing rattan, which also secures the extension of the asang asang. The scabbard is made of local wood and bound with plaited rattan strips. Its durability and sharpness can be comparable to the Japanese katana.

A collection of Moro keris types are archived in the United States National Museum.

Even before the arrival of Spain, the knowledge of metallurgy in the pre-colonial Philippines was neither tribal nor primitive. In fact, it was already sophisticated. Because if it was not, Panday Pira would not have come to be. The blades of these swords are a testament to the expertise of these early Filipinos.

The history of the Philippines from 1565 to 1898 is known as the Spanish colonial period, during which the Philippine Islands were ruled as the Captaincy General of the Philippines within the Spanish East Indies, initially under the Viceroyalty of New Spain, based in Mexico City, until the independence of the Mexican Empire from Spain in 1821. This resulted in direct Spanish control during a period of governmental instability there.

The first documented European contact with the Philippines was made in 1521 by Ferdinand Magellan in his circumnavigation expedition,1 during which he was killed in the Battle of Mactan. Forty-four years later, a Spanish expedition led by Miguel López de Legazpi left modern Mexico and began the Spanish conquest of the Philippines in the late 16th century. Legazpi's expedition arrived in the Philippines in 1565, a year after an earnest intent to colonize the country, which was during the reign of Philip II of Spain, whose name has remained attached to the country.

The Spanish colonial period ended with the defeat of Spain by the United States in the Spanish–American War and the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, which marked the beginning of the American colonial era of Philippine history.

The scabbard throat have small side elements lacking read more

650.00 GBP