Excellent Pre-Contact Example of a Stone Leilira Knife from Central or Northern Australia. A First Nations' Cultural Object

The handle made of Spinifex Resin (plant) and the quartz blade shaped by chipping and shaping with a harder stone. The term Leilira was first coined by Spencer and Gillen circa 1899, and is currently the archaeological term used to describe large blades produced in northern and central Australia."--------2006, Kevin Tibbett, "When East Is Northwest: Expanding The Archaeological Boundary For Leilira Blade Production," Australian Archaeology, p. 26.

"Spencer and Gillian (1899, 1904) coined the term lalira or leilira blades (from the Arrernte alyweke (indigenous Australians), or stone knife)

Ethnographically, these were men's fighting knives and were also mythologically and symbolically linked with subincision On occasions they were used for other purposes such as ritualised fighting, initiation ceremonies etc

The term 'Leilira blade' refers to very long flaked blades made in central and northern Australia that are triangular or trapezoidal in cross section. They are made by 'flaking' - removing a small piece of rock from a large piece, called a core, by striking it with a hammerstone. The core is usually held in the hand or rested in the person's lap or on the ground. Often one or both edges of the blade are retouched to create a dentated or notched edge or a rounded end.

Leilira blades are usually made from quartzite, a hard metamorphic rock that varies in colour from white to dark grey, but slate and other stones are also used. All of the blades shown are quartzite. The middle blade and the one on the far right were made from quartzite extracted from Ngillipidji stone quarry on Elcho Island, a major quarry in the region. Stone from Ngillipdiji quarry and finished blades made from the quarried stone were traded over long distances.

The has a handle or grip made from resin. The resin was heated and moulded around the unpointed end of the blade; when it cooled, it dried hard. paperbark, tied on with string. The plant-fibre scabbard may be pandanus paperleaf or bark.

Many First Nations' cultural objects were collected during the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land in 1948.

Indigenous Australian's were manufacturing stone tools for more than 40,000 years. The flaked stone tools they left behind are very simple. In fact, most of their hafted knives, spears and fighting picks were made from simple core struck blades that have little or no further modification. Bifacial flaking in Australia is rare compared to other regions of the world. The best examples are reported as large hand axe-like bifaces and small bifacially flaked points. Bifacial reduction is also reported in the manufacture of some ground stone axes. Australia's most famous bifacially flaked artifact is the more recent Kimberly point. The most famous blade knife is the resin hafted leilira knife. read more

675.00 GBP

Original 18th Century Scottish Fencible Regimental Basket Hilted Broadsword

With distinctive two part centrally welded basket, in sheet iron, with scrolls and thistles there over. Interesting original regimental swords of the 18th century, from Scottish regiments are very much sought after throughout the entire world. Scottish Fencible Regiment's swords are now jolly rare indeed, and they are highly distinctive in their most unique form. Fancy carved replacement grip. Some ironwork separation on the basket by the forte of the blade, but overall in good sound condition. Overall natural age surface pitting. Made for the war with Revolutionary France in the 1790's. The total number of British fencible infantry regiments raised during the Seven Years' War and the American War of Independence was nine, of which six were Scottish, two were English and one was Manx. The regiments were raised during a time of great turbulence in Europe when there was a real fear that the French would either invade Great Britain or Ireland, or that radicals within Britain and Ireland would rebel against the established order. There was little to do in Britain other than garrison duties and some police actions, but in Ireland there was a French supported insurrection in 1798 and British fencible regiments were engaged in some pitched battles. Some regiments served outside Great Britain and Ireland. Several regiments performed garrison duties on the Channel Islands and Gibraltar. A detachment of the Dumbarton Fencibles Regiment escorted prisoners to Prussia, and the Ancient Irish Fencibles were sent to Egypt where they took part in the operations against the French in 1801.

When it became clear that the rebellion in Ireland had been defeated and that there would be peace between France and Britain in 1802 (The preliminaries of peace were signed in London on 1 October 1801) the Fencible regiments were disbanded.

The British cavalry and light dragoon regiments were raised to serve in any part of Great Britain and consisted of a force of between 14,000 and 15,000 men. Along with the two Irish regiments, those British regiments that volunteered for service in Ireland served there. Each regiment consisted of eighteen commissioned officers and troops of eighty privates per troop. The regiments were always fully manned as their terms of service were considered favourable. At the beginning of 1800 all of the regiments were disbanded read more

2750.00 GBP

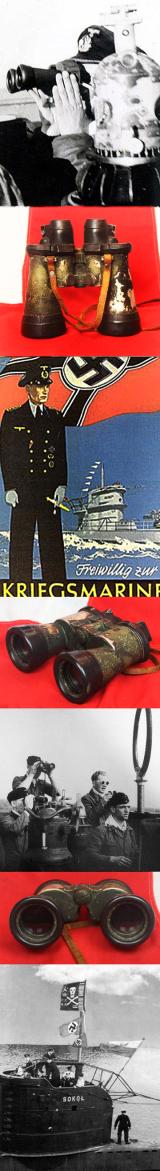

A Superb Pair of WW2 German Kriegsmarine "U-boat" Fixed-Focus Binoculars. “Doppelfernrohr 7 X 50 für U-Boote ‘U-Bootglas 7X50’”

These are an original pair of German, WW2 U-Boat commanders binoculars, and for desirability simply cannot be bettered. This delightful pair are in fabulous condition, with all the rubbers and lenses in lovely condition for age, with all the usual wear as to be expected.

Third Reich WW2 period code marked. With superb fixed focusing, excellent optics and lenses, just a very little condensation misting.

Winston Churchill claimed that the 'U-boat peril' was the only thing that ever really frightened him during WWII. This was when German submarines attacked the Atlantic lifeline to try to starve Britain into submission.

In WWII the British troop ship, RMS Laconia, was sunk by a German U-boat. The U-boat captain Werner Hartenstein immediately ordered the rescue of as many survivors as possible, taking 200 people on board, with another 200 in lifeboats. Although, it is fair to say that not all U-boat commanders were quite so considerate as he was. The U-Boat 7 X 50 binocular was manufactured from 1941 – 1945 specifically for use aboard submarines and was officially designated as the “Doppelfernrohr 7 X 50 für U-Boote ‘U-Bootglas 7X50’”. They were usually made by Zeiss but a smaller number were also manufactured by Emil Busch Rathenow (wartime code “cxn”).

It had three variations. The first was made from 1941-1943, lacked rubber armour and had hinged fold-back Bakelite eyecups. The second was made probably only in 1943 and had rubber armour without fold-back eyecups. The third was made from 1943-1945 and is identical to the second except for having a larger diameter eyelens. The first type is the rarest many being lost during service use.

The build of this binocular is remarkable and unequaled by WWII hand-held binoculars, and some believe never bettered since the war either. It is a fixed focus design for maximum sealing and weatherproofing. The primary user of the binocular could, however, set the focus to his eyesight by removing the rubber armour from the prism plates to access a large focus screw at the base of each eyepiece which could be adjusted using a screwdriver.

During World War II, U-boat warfare was the major component of the Battle of the Atlantic, which lasted the duration of the war. Germany had the largest submarine fleet in World War II, since the Treaty of Versailles had limited the surface navy of Germany to six battleships (of less than 10,000 tons each), six cruisers, and 12 destroyers.

In the early stages of the war the U-boats were extremely effective in destroying Allied shipping; initially in the mid-Atlantic where a large gap in air cover existed until 1942, when the tides changed. The trade in war supplies and food across the Atlantic was extensive, which was critical for Britain's survival. This continuous action became known as the Battle of the Atlantic, as the British developed technical defences such as ASDIC and radar, and the German U-boats responded by hunting in what were called "wolfpacks" where multiple submarines would stay close together, making it easier for them to sink a specific target. Later, when the United States entered the war, the U-boats ranged from the Atlantic coast of the United States and Canada to the Gulf of Mexico, and from the Arctic to the west and southern African coasts and even as far east as Penang. The U.S. military engaged in various tactics against German incursions in the Americas; these included military surveillance of foreign nations in Latin America, particularly in the Caribbean, to deter any local governments from supplying German U-boats.

Because speed and range were severely limited underwater while running on battery power, U-boats were required to spend most of their time surfaced running on diesel engines, diving only when attacked or for rare daytime torpedo strikes. The more ship-like hull design reflects the fact that these were primarily surface vessels that could submerge when necessary. This contrasts with the cylindrical profile of modern nuclear submarines, which are more hydrodynamic underwater (where they spend the majority of their time), but less stable on the surface. While U-boats were faster on the surface than submerged, the opposite is generally true of modern submarines. The most common U-boat attack during the early years of the war was conducted on the surface and at night. This period, before the Allied forces developed truly effective antisubmarine warfare tactics, which included convoys, was referred to by German submariners as "die glückliche Zeit" or "the happy time."

The neck strap has separated, the rubber armour has overall age cracking as usual, the original eye protectors have has replacement post war retaining screws. Plus usual paint loss. Bear in mind they were subjected to some years at sea, over 80 years ago, as combat service surveillance equipment, above and below deck, in some of the most unpleasant weather one can experience, yet still survive till today as fully functioning binoculars as was originally intended eight decades ago. No doubt in some part due to their original owner’s skill or good fortune {the U-Boat commander}, at avoiding being sunk by the indomitable Royal Navy ships or RAF spotter planes. read more

2450.00 GBP

A Good King George IIIrd Period Belgian Light Dragoon Type Percussion Holster Pistol

Based very comparably to the British 1756 Light Dragoon pattern holster pistol, but made circa 1822. A very strong an robust pistol bearing numerous Belgian proof and military inspection stamps, and a Liege 1811 barrel proof stamp, brass skull-crusher butt cap with lanyard ring. percussion action, finest walnut stock that its surface has been fully relief carved with a snakeskin pattern, a cross, a heart and a serpent, and has a fabulous natural patina. strong mainspring, overall 16 inches long, 9 inch barrel. Set to a hair-trigger action read more

495.00 GBP

One Amazing {of Two} 17th Century Iron Cannon Balls From 'Queen Elizabeth's Pistol', A 24 Foot Long Basilisk Cannon. The Cannon Balls Were Found in the 19th Century. A Fabulous Relic From 'The Siege of Hull' During the English Civil War

'Queen Elizabeth's Pistol', was the Tudor nickname of a fabulous cannon presented to Queen Elizabeth's father King Henry the VIIIth. In the English Civil war it was called 'the great Basilisco of Dover' and it was used in the English Civil war, first by the Parliamentarian artillery train forces of the Earl of Essex, it was captured, at Lostwithiel in August 1644, then used by the King's Artillery train, and then retaken by the Parliamentarian forces.

The basilisk got its name from the mythological basilisk: a fire-breathing venomous serpent that could cause large-scale destruction and kill its victims with its glance alone. It was thought that the very sight of it would be enough to scare the enemy to death

The cannon balls were recovered from the besieged area of Hull, and sold at auction in the 19th century, and since then, they have been in the same family's ownership. We are selling them separately, and priced individually.

The 24 foot long bronze cannon was cast in 1544 by Jan Tolhuys in Utrecht. It is thought to have been presented to Henry VIII by Maximiliaan van Egmond, Count of Buren and Stadtholder of Friesland as a gift for his young daughter Elizabeth and is known to have been referred to as Queen Elizabeth's Pocket Pistol by an article in the Gentleman's Magazine from 1767. The cannon is thought to have been used during the English Civil War, described as 'the great Basilisco of Dover' amongst other ordnance captured by Royalist forces from the Earl of Essex in Cornwall in 1644, later used at the siege of Hull and recaptured by Parliamentarians. The barrel is decorated in relief with fruit, flowers, grotesques, and figures symbolizing Liberty, Victory and Fame. The gun carriage was commissioned by the Duke of Wellington in the 1820s, when it was then known as Queen Anne's gun, cast from French guns captured at Waterloo.

Maximilian van Egmont, Count of Buren, Stadtholder of Friesland, 1509-1548, was a distinguished military commander in the service of the Emperor. He was on terms of friendship with Henry VIII and commanded the Imperial contingent at the Siege of Boulogne in 1544. The gun may have been installed at Dover as soon as it was received in England. In the inventory of the Royal possessions drawn up after the King's death in 1547 "the Ordynance and Munycions of Warre......which were in the black bulworke at the peire of Dover....included Basillisches of brasse .....oone Basillisches shotte ......Cl ti"

A popular rendering of the inscription on the gun was 'Load me well and keep me clean, I'll send a ball to Calais Green'. A footnote in the 1916 inventory suggests that this is a doubtful boast since ' Calais Green' was a part of Dover. There appears, however, to be no basis for this statement.

We show in the gallery two of the Basilisk cannon balls recovered outside the curtain wall of Pontefract Castle

Pontefract Castle sits on the edge of the medieval market town. Conservation work is being undertaken with the ambition of making Pontefract a key heritage destination within West Yorkshire. The £3.5m Heritage Lottery funded project is known as the Key to the North, after the title bestowed upon the castle by Edward I. During the project, workmen at the castle recovered seven cannonballs from a section of the castle’s curtain wall.

This cannon ball {a pair to our other one} was acquired from an auction, of recovered Civil War relics from the Siege of Hull, that was held in Hull in the early Victorian period, and acquired from the buyers directly descended family, by us, very recently.

The basilisk was a very heavy bronze cannon employed during the Late Middle Ages. The barrel of a basilisk could weigh up to 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) and could have a calibre of up to 5 inches (13 cm). On average they were around 10 feet long, though some, like Queen Elizabeth's Pocket Pistol, were almost three times that length.

The basilisk got its name from the mythological basilisk: a fire-breathing venomous serpent that could cause large-scale destruction and kill its victims with its glance alone. It was thought that the very sight of it would be enough to scare the enemy to death

The Basilisk cannon used in the Civil War was a most specific calibre of almost 5 inches, and fired this distinct size of round shot cannon ball munition of just over 4 1/2 inch diameter

We also show in the gallery a photograph of 'Queen Elizabeth's Pistol'. in Dover Castle, with a stack of the very same sized cannon balls.

The ball is very surface russetted, but still spherical and very good for its age,

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading read more

695.00 GBP

A Stunning, Early, Signed Munemitsu, Bizen School Koto Blade Katana With Hi Circa 1480. A Most Beautiful And Elegant Ancient Samurai Sword By a Master Smith Of the 15th Century

The tsuka-ito {silk hilt binding} was in a pretty poor state, so we are having the {hilt} tsuka re-wrapped, thus we are photographing it at present with its mounts separate, and with the blade and saya. before re-fitting.

Possibly by Bishu Osafune Munemitsu {a smith from the Bunmei reign in the Koto era}

The blade is absolutely beautiful, with hirazukuri, iori-mune, very elegant zori, chu-kissaki and carved with broad and deep hi on both sides, the forging pattern is beautiful, and a gunome-midare of ko-nie, deep ashi, hamon, the tang is original, and full length, and it is mounted with a silver habaki. The blade has a fabulous blocking cut on the mune, a most noble and honourable battle scar that is never removed and kept forever as a sign of the combat blocking move that undoubtedly saved the life of the samurai, and will thus be never removed.

The tsuka has an iron Higo school kashira, a beautiful signed shakudo-nanako fuchi with very fine quality takabori decoration.

Its tsuba is beautiful with a takebori design of Mount Fuji with dragon flying in the sky above, with highlights in gold, silver and copper. The Edo menuki are of a shakudo and gold representation group of samurai armour upon a tachi, and a shakudo and gold dragon {clutching an ancient Ken double edged straight sword with lightning maker} a Edo Antique Ken maki Ryu zu

What with the defensive cut, its shape and form, this fabulous sword has clearly seen combat, yet it is in incredibly beautiful condition for its great age, and it is a joy to behold. Once the tsuka binding has been fitted and re-bound we will re-photograph it in all its glory once more. read more

Price

on

Request

A 1000 Year Old Survivor From Antiquity. Early Crusades Reliquary, Pectoral, Encolpion Cross. Containing A Shard of The True Cross. Hinged Cross Of the Ancient Holy Land. Likely Presented to a Warrior Knight Before for the Crusade, by a Bishop

An absolute beauty, worthy of the British Museum or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York,with superb low relief detailing, reflecting in the quality of the entire piece. This was clearly made to the standard for gifting to a knight of such as a warrior Knights Templar.

The front is decorated with the relief cast image of Mary displayed in the Orans position in prayer. Depicted on the reverse is the figure of Corpus Christi on the cross.

Obviously with light signs of natural old surface wear, but it has survived superbly complete, especially considering after all the extraordinary turmoil, privations, and indeed likely combat the knight owner would have experienced during the earliest crusades to the Holy Land.

With a deep relief cast bronze Jesus Christ in a crucifix pose on the obverse side with four

This is a two part, hinged bronze reliquary cross, which is complete, and may once have contained part of the true cross.

The cross is composed of two bronze boxes with were formed and joined by hinges. A thick suspension ring enabled the encolpion to be worn as a pectoral pendant. The reliquary was probably thought to contain a splinter of the True Cross. For other reliquary crosses, see the exhibition catalogue “Kreuz und Kruzifix” (Diocese Museum of Friesing, Germany, 2005) – pgs 174-175. Another example in bronze is pictured in Pitirakis, "Les Croix-Reliquares Pectorales Byzantine", Paris, 2006, 162. Byzantine representations of the Crucifixion which show Christ wearing a robe are normally earlier than those in which he wears a loincloth.

The hollow portion formed inside the box was intended for the sacred relic that the faithful would have worn around the neck. Part four of the amazing small collection of antiquites including Crusades period Crucifixes and reliquary crosses for the early Anglo Norman Crusader knights and Jerusalem pilgrims.

As used in the early Crusades Period by Knights, such as the Knights of Malta Knights Hospitaller, the Knights of Jerusalem the Knights Templar, the Knights of St John.

The new Norman rulers were culturally and ethnically distinct from the old French aristocracy, most of whom traced their lineage to the Franks of the Carolingian dynasty from the days of Charlemagne in the 9th century. Most Norman knights remained poor and land-hungry, and by the time of the expedition and invasion of England in 1066, Normandy had been exporting fighting horsemen for more than a generation. Many Normans of Italy, France and England eventually served as avid Crusaders soldiers under the Italo-Norman prince Bohemund I of Antioch and the Anglo-Norman king Richard the Lion-Heart, one of the more famous and illustrious Kings of England. An encolpion "on the chest" is a medallion with an icon in the centre worn around the neck upon the chest. This stunning and neck worn example is bronze three part with its hinged top. 10th to 12th century. The hollow portion formed inside the cross was intended for the sacred relic that the faithful would have worn around the neck. The custom of carrying a relic was largely widespread, and many early bronze examples were later worn by the Crusader knights on their crusades to liberate the Holy Land. Relics of the True Cross became very popular from the 9th century, and were carried in cross-shaped reliquaries like this, often decorated with enamels, niellos, and precious stones. The True Cross is the name for physical remnants from the cross upon which Jesus Christ was crucified. Many Catholic and Orthodox churches possess fragmentary remains that are by tradition believed to those of the True Cross. Saint John Chrysostom relates that fragments of the True Cross were kept in reliquaries "which men reverently wear upon their persons". A fragment of the True Cross was received by King Alfred from Pope Marinus I (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, year 883). An inscription of 359, found at Tixter, in the neighbourhood of Sétif in Mauretania, was said to mention, in an enumeration of relics, a fragment of the True Cross, according to an entry in Roman Miscellanies, X, 441.

Fragments of the Cross were broken up, and the pieces were widely distributed; in 348, in one of his Catecheses, Cyril of Jerusalem remarked that the "whole earth is full of the relics of the Cross of Christ," and in another, "The holy wood of the Cross bears witness, seen among us to this day, and from this place now almost filling the whole world, by means of those who in faith take portions from it." Egeria's account testifies to how highly these relics of the crucifixion were prized. Saint John Chrysostom relates that fragments of the True Cross were kept in golden reliquaries, "which men reverently wear upon their persons." Even two Latin inscriptions around 350 from today's Algeria testify to the keeping and admiration of small particles of the cross. Around the year 455, Juvenal Patriarch of Jerusalem sent to Pope Leo I a fragment of the "precious wood", according to the Letters of Pope Leo. A portion of the cross was taken to Rome in the seventh century by Pope Sergius I, who was of Byzantine origin. "In the small part is power of the whole cross", says an inscription in the Felix Basilica of Nola, built by bishop Paulinus at the beginning of 5th century. The cross particle was inserted in the altar.

The Old English poem Dream of the Rood mentions the finding of the cross and the beginning of the tradition of the veneration of its relics. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle also talks of King Alfred receiving a fragment of the cross from Pope Marinus (see: Annal Alfred the Great, year 883). Although it is possible, the poem need not be referring to this specific relic or have this incident as the reason for its composition. However, there is a later source that speaks of a bequest made to the 'Holy Cross' at Shaftesbury Abbey in Dorset; Shaftesbury abbey was founded by King Alfred, supported with a large portion of state funds and given to the charge of his own daughter when he was alive – it is conceivable that if Alfred really received this relic, that he may have given it to the care of the nuns at Shaftesbury

Most of the very small relics of the True Cross in Europe came from Constantinople. The city was captured and sacked by the Fourth Crusade in 1204: "After the conquest of the city Constantinople inestimable wealth was found: incomparably precious jewels and also a part of the cross of the Lord, which Helena transferred from Jerusalem and which was decorated with gold and precious jewels. There it attained the highest admiration. It was carved up by the present bishops and was divided with other very precious relics among the knights; later, after their return to the homeland, it was donated to churches and monasteries.To the category of engolpia belong also the ampullae, or vials or vessels of lead, clay or other materials in which were preserved such esteemed relics as oil from the lamps that burned before the Holy Sepulchre, and the golden keys with filings from St. Peter's chains, one of which was sent by St. Gregory the Great to the Frankish King Childebert.

The last time the Pope gave a piece of the true cross was for the coronation of King Charles IIIrd set within the cross for Wales. The relics of what is known as the True Cross were given to King Charles by Pope Francis, as a coronation gift. The cross uses Welsh materials such as slate, reclaimed wood, and silver from the Royal Mint in Llantrisant. King Charles hammered the hallmark onto the silver used in the cross.

Encolpion, a different anglicization of the same word, covers the early medieval tradition in both Eastern and Western Christianity. Superb condition overall, with both the top and bottom hinges

The natural, aged, surface bronze patination over the past 1000 years is in superb condition, and remarkably still sealed

Encolpia were small pendants worn around the neck, and examples have been found tracing back to Late Antiquity. The cross shape was the most popular symbol for such amulets, as the silhouette was believed to have apotropaic qualities. Many encolpia were designed to hold reliquaries, as does ths beauty,.The reliquary was believed to work in tandem with the talismanic qualities of the cross-shape to protect the wearer from harm and evil. Such pieces were very popular in the crusades, and were made in an assortment of materials, from gold and silver, to bronze and lead.

6cm long approx

See; Les Croix-Reliquaires Pectorales Byzantines En Bronze, Paris, 2006, p.37, for similar.

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity read more

995.00 GBP

Most Rare and Intriguing, Original 1300's, Medieval Ecclesiastical Personal Bronze Seal Matrix of Two Figures Each in a Lancet Arch, Engraved At The Rim St Philip {the Apostle}. Over 700 Years Old. With Potential Connection to Kirkham Priory, Yorkshire

Made and used from the early Plantagenet period of King Edward Ist, also known as Edward Longshanks or Hammer of the Scots.

A most similar example to one found concealed and lost for centuries within a box in Lincoln Cathedral in 2018. Their seal depicts the patron saint of Lincoln Cathedral, the Virgin Mary, who is shown crowned and seated on a throne, holding the infant Christ in her lap. In her left hand she holds a flowering rod topped by a fleur-de-lis. Another seal they hold was for use by the Dean and Chapter in the 1100's.

As this Plantagenet period seal matrix was discovered in Yorkshire {over 40 years ago} it may well have a connection to the 1300's medieval Kirkham Priory, as its gatehouse has within two lancet arches figures of St Philip and St Bartholomew. The arches on the seal may indeed by those saints. And this seal mentions St. Philip.

Seals were attached to documents, usually legal ones, and the most famous of all documents bearing such a seal was the Magna Carta signed by King John. Documents were sealed by means of strips of parchment or silk laces which had been inserted into the bottom of the document. They were the medieval equivalent of a signature. At a time when few could read, or write, they were a useful way of guaranteeing that the people who were supposed to be agreeing to what was in a document had agreed to it. They were made by warming a piece of wax, pressing it around the lace or parchment and flattening it between the two halves of the seal-die, which were locked together until the wax cooled. Some seals were made of gold or silver, which was really a way of showing off the wealth of the owner.

Philip was born in Bethsaida, Galilee. He may have been a disciple of John the Baptist and is mentioned as one of the Apostles in the lists of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and in Acts. Aside from the lists, he is mentioned only in John in the New Testament. He was called by Jesus Himself and brought Nathanael to Christ. Philip was present at the miracle of the loaves and fishes, when he engaged in a brief dialogue with the Lord, and was the Apostle approached by the Hellenistic Jews from Bethsaida to introduce them to Jesus. Just before the Passion, Jesus answered Philip's query to show them the Father, but no further mention of Philip is made in the New Testament beyond his listing among the Apostles awaiting the Holy Spirit in the Upper Room. According to tradition he preached in Greece and was crucified upside down at Hierapolis under Emperor Domitian. His feast day is May 3.

Bronze was the metal usually used for seal-dies, because it was hard. This meant that dies could be engraved with more detail than was possible with other metals and that they would not wear away quickly with repeated use.

Since they were the equivalent of a signature, they were valuable objects and were usually kept under lock and key. There are tales of monks using the seals to embezzle money from their monasteries.

A beautiful bronze seal with pierced trefoil lug; incuse image of two facing figures each in a lancet arch, supplicant in D-shaped panel below;

blackletter legend to rim, only partially decipherable to us, as 'St Philip...

In the 13th century, ecclesiastical jurisdiction in Europe, especially England, was extensive, covering marriage, wills (probate), defamation, church property (tithes/benefices), clergy discipline, and heresy, often overlapping with secular law and extending its reach where royal courts were weak, with appeals moving up through archdeacons to archbishops and ultimately to the papal courts in Rome, marked by intense jurisdictional struggles, like those around Canterbury.

For reference the Lincoln Cathedral discovered seal matrix;

Experts, including academics from the University of East Anglia and the British Museum, agree that the matrix dates from the early medieval period.

Lloyd de Beer, Ferguson Curator of Medieval Europe at the British Museum, said: “Institutional seal matrices like this are extremely rare, especially in silver and from such an early date. The Lincoln seal is a joy to behold. It is a masterpiece of micro sculpture made by a truly skilled goldsmith. What’s more, the reverse contains beautiful swirls of niello surrounding an enthroned Christ.”

Its prior existence was known of, and “the Great Seal of the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral” had a world-wide reputation as a rare piece of 12th century craftsmanship, but until recently no one in living memory had seen or handled the real object.

https://museumcrush.org/the-12th-century-medieval-seal-matrix-found-in-a-cathedral-box/

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity read more

495.00 GBP

A Fine Shinto Period Handachi Mounted Armour & Kabuto Cleaving Katana Signed Nobutsugu, With a Fabulous Notare Hamon, Handachi Mounted with Tsuba Of Watanabe no Tsuna and The Rashomon Demon, Ibaraki-Dōji, At The Gate of the Modoribashi Bridge

The blade is signed Nobutsugu, that is likely Higo kuni Dotanuki Nobutsugu, circa 1590, a master smith famed for his swords of great heft and incredibly robust, which this sword, most unusually, clearly demonstrates in abundance. The blades gunome notare hamon is simply fabulous, and the blade is in stunning condition.

The original Edo period urushi lcquer is stunning, designed and a combination of black over dark red that is, with incredibly subtlety, relief surface carved with mokume (木目) which is a Japanese term meaning "wood grain" or "wood eye," and over decorated with Katchimushi {dragonflies}. Truly wonderous skill is demonstrated in this fabulous design, that is almost invisible to the unobservant eye. A masterpiece of the urushi lacquer art.

The saya is also wrapped in its old and fine original silk sageo cord.

The sukashi tsuba is made in patinated copper, the type of shape known as maru gata, and with the design of the legend of ‘Watanabe no Tsuna and the Rashomon demon’ that tells of the 10th-century warrior who fought and severed the arm of an oni (demon), named Ibaraki, at Kyoto's ruined Rashomon Gate, the Modoribashi Bridge. A story most popular in Japanese folklore, art (like ukiyo-e prints), and theatre, that is culminating in the demon tricking Tsuna into returning the arm by disguising itself as his aunt.

The blade is extraordinary, that although it is not long, it is immensely powerful, and possesses the thickness, strength and heft, of both an armour & helmet piercing sword, in fact, as soon as one handles this sword for the first time, it is immediately obvious as to the character of the power of this blade. Specifically designed as it was, for an incredibly strong cut, that could cleave a samurai, within his armour and kabuto helmet, clean in two. Or, even possibly, as it bears the tsuba of Watanabe no Tsuna, the samurai that legendarily severed an arm off the demon of the Rashomon gate, it is its sword mount that is meant to symbolise the very essence of this sword, as one so powerful, it could even cut through the arm of an Oni demon.

It is mounted in a full suite of fine, hand engraved, handachi mounts, upon both the tsuka and saya, of sinchu, hand engraved with florid scrolls, and sinchu menuki surface decorated with gilded takebori flowers, and with fine, golden brown tsukaito, bound over traditional samegawa {giant rayskin}

The blade has a fabulous, deep and profound, notare hamon, that is wonderfully defined.

Han-dachi mounted swords originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from tachi mounting to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up, when on foot, but edge down on horseback, as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need for a sword to be worn in either style.

The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or their daimyo lords, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could not only read, they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

The story that is told by the tsuba;

One stormy night, Watanabe no Tsuna, a samurai retainer of Minamoto no Yorimitsu, was waiting at the dilapidated Rashomon Gate. A demon, Ibaraki-doji, was revealed and attacked him, tugging at his helmet. However,

Tsuna, a most capable and valiant warrior, drew his sword and sliced off the demon's arm in a fierce struggle.

The demon fled, leaving its arm behind, which Tsuna took as a trophy and locked within a chest.

A few days later, an old woman, claiming to be Tsuna's aunt (Mashiba), visited him. She asked to see the severed arm, and when Tsuna opened the chest, she revealed herself as Ibaraki himself in disguise, grabbed his arm, and escaped.

The story of Watanabe no Tsuna (the hero) and Ibaraki-doji (the demon), combatting at the decaying Rashomon Gate in Kyoto, a place associated with ghosts and demons.

It represents themes of bravery, cunning, supernatural encounters, and the deceptive nature of appearances.

This legend became a famous motif in Japanese art, particularly in woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) by artists like Chikanobu and Yoshitoshi, depicting the dramatic fight and the demon's escape.

It's a classic tale featured in Noh, Kabuki, and other popular narratives.

The symbolism of the Katchimushi {dragonfly} decor of the saya;

Japan was once known as the “Land of the Dragonfly”, as the Emperor Jimmu is said to have once climbed a mountain in Nara, and looking out over the land, claimed that his country was shaped like two Akitsu, the ancient name for the winged insects, mating.

Dragonflies appeared in great numbers in 1274 and again in 1281, when Kublai Khan sent his Mongol forces to conquer Japan. Both times the samurai repelled the attackers, with the aid of huge typhoons, later titled Kamikaze (the Divine Winds), that welled up, destroying the Mongol ships, saving Japan from invasion. For that reason, dragonflies were seen as bringers of divine victory.

Dragonflies never retreat, they will stop, but will always advance, which was seen as an ideal of the samurai. Further, although the modern Japanese word for dragonfly is Tombo, the old (Pre Meiji era) word for dragonfly was Katchimushi. “Katchi” means “To win”, hence dragonflies were seen as auspicious by the samurai.

The condition of all parts is excellent with just a few, very small, but usual combat bruises, to the old and original, Edo period lacquer surface to the swords saya.

Overall the sword is 38 inches long, and the blade 26 inches long, habaki to tip. read more

6950.00 GBP

An Ancient Roman Eastern Empire Battle Axe, 4th Cent. & Through The 1st Millenia A.D. An Amazing, Original, Collectors Item From the Ancient Roman Empire of Constantine The Great. A Throwing Axe Often Classified as The Arch Shaped Axe, The Francisca

This is a typical axe for the Eastern Roman Empire legionary and warrior. From the time of Emperor Constantine 'The Great' and used to The beginning of Byzantium period. A blade form that evolved slightly, and thus remained popular as a throwing axe right into the early Viking and Anglo Saxon warrior eras. As a companion throwing axe, used alongside the Danish Huscarles great axe.

There is a very similar arch shaped example, but with a slanting socket, in the British Museum, classified as a throwing axe, or Francisca from circa 500 a.d. found in a war grave at the foot of Mount Blanc. See photo 7 in the gallery. Museum number

1856,0701.1416

The Battle of Cibalae was fought in 316 between the two Roman emperors Constantine I (r. 306–337) and Licinius (r. 308–324). The site of the battle, near the town of Cibalae in the Roman province of Pannonia Secunda, was approximately 350 kilometers within the territory of Licinius.

Constantine won a resounding victory, despite being outnumbered.

The opposing armies met on the plain between the rivers Sava and Drava near the town of Cibalae .

The battle lasted all day. The battle opened with Constantine's forces arrayed in a defile adjacent to mountain slopes. The army of Licinius was stationed on lower ground nearer the town of Cibalae, Licinius took care to secure his flanks. As the infantry of Constantine needed to move forward through broken ground, the cavalry was thrown out ahead, to act as a screen. Constantine moved his formation down on to the more open ground and advanced against the awaiting Licinians. Following a period of skirmishing and intense missile fire at a distance, the opposing main bodies of infantry met in close combat and fierce hand-to-hand fighting ensued. This battle of attrition was ended, late in the day, when Constantine personally led a cavalry charge from the right wing of his army. The charge was decisive, Licinius' ranks were broken. As many as 20,000 of Licinius' troops were killed in the hard-fought battle. The surviving cavalry of the defeated army accompanied Licinius when he fled the field under the cover of darkness

It is a matter of debate when the Roman Empire officially ended and transformed into the Byzantine Empire. Most scholars accept that it did not happen at one time, but that it was a slow process; thus, late Roman history overlaps with early Byzantine history.

Constantine I (the Great) is usually held to be the founder of the Byzantine Empire. He was responsible for several major changes that would help create a Byzantine culture distinct from the Roman past.

As emperor, Constantine enacted many administrative, financial, social, and military reforms to strengthen the empire. The government was restructured and civil and military authority separated. A new gold coin, the solidus, was introduced to combat inflation. It would become the standard for Byzantine and European currencies for more than a thousand years. As the first Roman emperor to claim conversion to Christianity, Constantine played an influential role in the development of Christianity as the religion of the empire. In military matters, the Roman army was reorganised to consist of mobile field units and garrison soldiers capable of countering internal threats and barbarian invasions. Constantine pursued successful campaigns against the tribes on the Roman frontiers the Franks, the Alamanni, the Goths, and the Sarmatians, and even resettled territories abandoned by his predecessors during the turmoil of the previous century.

The age of Constantine marked a distinct epoch in the history of the Roman Empire. He built a new imperial residence at Byzantium and renamed the city Constantinople after himself (the laudatory epithet of New Rome came later, and was never an official title). It would later become the capital of the empire for over one thousand years; for this reason the later Eastern Empire would come to be known as the Byzantine Empire. His more immediate political legacy was that, in leaving the empire to his sons, he replaced Diocletian’s tetrarchy (government where power is divided among four individuals) with the principle of dynastic succession. His reputation flourished during the lifetime of his children, and for centuries after his reign. The medieval church upheld him as a paragon of virtue, while secular rulers invoked him as a prototype, a point of reference, and the symbol of imperial legitimacy and identity. The Varangian Guard was an elite unit of the Byzantine Army, whose members served as personal bodyguards to the Byzantine Emperors. The Varangian Guard was known for being primarily composed of recruits from northern Europe, including Norsemen from Scandinavia and Anglo-Saxons from England. The recruitment of distant foreigners from outside Byzantium to serve as the emperor's personal guard was pursued as a deliberate policy, as they lacked local political loyalties and could be counted upon to suppress revolts by disloyal Byzantine factions.

These axe form and evolved into somewhat similar correspondent to the type 1 of the classification made by the Kirpichnikov for early axes. Particularly, it seems akin to the specimens of Goroditsche and Opanowitschi, dated in the turn of 10th - 11th centuries however, due to its earlier ageits shape is slightly different, considering the strong influence of the Roman Armies on the much later Baltic ones in 11th century.

The general Nikephoros Ouranos remembers in his Taktika (56, 4) that small axes were used at the waist of the selected archers of infantry : "You must select proficient archers - the so called psiloi - four thousand. These men must have fifty arrows each in their quivers, two bows, small shields and extra bowstrings. Let them also have swords at the waist, or axes, or slings in their belts".

The axe was inserted in its wooden shaft and fixed to it by means of dilatation of the wood, dampened by water.

The Byzantine Empire is the great Greek-language Christian empire that emerged after 395AD from the eastern part of the Roman Empire, Thanks to efficient government and clever diplomacy that divided its many enemies, the empire survived. Much diminished after 1204 AD when it was sacked by Christian Crusaders from the west en route to liberate Jerusalem, it finally fell to the Turks in 1453--indeed its fall is often used to date the end of the Middle Ages. Its capital was Constantinople, built on the site of the Greek colony of Byzantium and which is now known as Istanbul). The center of Orthodox Christianity, it is famous as well for its art and culture. The inhabitants of the empire referred to themselves as 'Romans' and considered themselves as such, the term 'Byzantine' not being used to describe the empire and its peoples until the seventeenth century, but after the seventh century the language of empire changed from Latin to Greek.

Almost every iron weapon that has survived through the millennia, to today, from this ,era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one.

Condition; very nicely preserved with small projecting upper front point lacking, likely a battle loss.

For reference see;; ROACH SMITH C. 1854. Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities, Collected by, and the Property of, Charles Roach Smith, privately printed, p. 102 no. 544

Axe; Registration number

1856,0701.1416

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1856-0701-1416 read more

975.00 GBP