Japanese

A Very Rare WW2 Japanese Shell Case From a Type 11 37mm Infantry Anti Tank Gun

Souvenir of an British officer gifted to him by an Australian officer, who served in the Pacific War in WW2. All Japanese munitions from WW2 are incredibly rare to see in the UK as so few returning soldiers bothered to collect them and bring them home, plus all WW2 arms of all kinds were destroyed in Japan from 1945. For them it was a determined effort to wipe out all mention and thought of WW2 and to eradicate any reminder of the shame. All marked items of that period were banned, and in fact a rule that is still enforced in Japan today. The shell schematics are; Calibre Diameter: 37mm

Case Length: 132mm

Rim: R

Round Index: Shell Type 95 AP

Projectile Index: Type 95 AP

Projectile Weight: 0,67000 kg

Filler Weight: 0,03500 kg

Usage: Type 11 37mm Infantry Gun, Type 94 37mm Anti-Tank Gun & Type 94 37mm Tank Gun

Armour piercing/high Explosive round for Type 11 Infantry Gun, early Type 94 AT & Tank Guns. Inert and safe not suitable for export. read more

125.00 GBP

A Super Early Samurai Sword Katana Tsuba, Kanayama and Ono School

Kanayama and Ono school tettsu tsuba, Circa 1400

Kanayama Tsuba exhibit a well forged iron with a hammered surface with prominent Tsuchime similar to Owari Tsuba but with stronger Tekkotsu visible in the rim and surface. The origin of Kanayama tsuba is still not a hundred percent clear, but most sources name a city close to Nagoya in the Owari province. In the early Edo period Ono Tsuba developed out of the Kanayama school and continued their tradition with various designs but a bit smaller in size.

The Kanayama school

Beginning in mid Muromachi to the end of Genroku (ca. 1400 to 1710). For purposes of study, the period of production is divided into three sections: the first period is the Muromachi age, second period is Momoyama age, and the third period are the pieces made in Kyoto during the Edo age. Normally round, sometimes oval.

the tsuba's seppa dai is a very good shape, squarish at top and bottom. Usually Thickness 3 to 5.09mm. this tsuba is 5 mm thick . It appears slightly large for the size of the tsuba and slightly more oblong than those found on Owari tsuba.

Many tsuba of the school have thin, raised square peripheral rims (later examples have rounded rims) with 'tekkotsu' visible.

Design Characteristics:

This school would seem to be the earliest to use ji-sukashi (positive silhouette). Most of the designs are plain, direct, and abstract, consisting largely of straight or curved lines that produce a feeling of great dignity. The openwork is so extensive that the remaining metal portions are very fine and slender.

Antique Japanese koshirae [Japanese samurai sword mounts, tsuba and fittings] are considered as fine object d'art in their own right, and have been collectable as individual items or sets, since the Edo period. They were often removed from swords, mounted in small cases, and respectfully admired for display as items of the highest quality workmanship, and symbols of the noble samurai, in their own right. Some koshirae collectors never actually have any interest in the blades themselves, and individual pieces can attain values of tens of thousands of pounds, and there are many multi million pound collections, in and out of museums, comprising of some of the finest examples of Japanese un-mounted sword fittings from the samurai historical period.

70mm across read more

675.00 GBP

Iron Round Chisa Katana or Wakazashi Tsuba With Amidayasuri and Wave Rim

Koto period circa 1550 with very finely chisseled designs. Tsuba are usually finely decorated, and are highly desirable collectors' items in their own right. Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other. read more

375.00 GBP

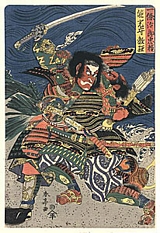

Europe’s Leading Original Samurai Sword Specialists

After 50 years personal experience by Mark, since 1971, we are Europe’s leading samurai sword specialists, with hundreds of swords to view and buy online 24/7, or in our store on a personal visit, 6 days a week. In fact we know of no better and varied original samurai sword selection for sale under one roof outside of Japan, or probably, even within it. Hundreds of original pieces up to 800 years old. Whether we are selling to our clients representing museums around the globe, the world’s leading collectors, or simply a first time buyer, we offer our advice and guidance in order to assist and guide the next custodian of a fine Japanese sword, to make the very best choice for them.

Both of the partners of the company have spent literally all of their lives surrounded by objects of history, trained, almost since birth in the arts and history. Supervised and mentored, first by their grandfather, then their father, who left the RAF sometime after the war, to become one of the leading antique exporters and dealers in the entire world. Selling, around the whole world, in today’s equivalent, hundreds of millions of pounds of antiques and works of art. Both Mark and David were incredibly fortunate to be mentored by some of the world’s leading experts within their fields of antiques and militaria. Mark has been a director and partner in the family businesses since 1971, but long before that he was handling and buying swords and flintlocks since he was just seven years old, obviously in a very limited way though, naturally. David, Mark’s younger brother, also started collecting militaria when he was seven, and as you will by now guess, history, antiques and militaria is simply in their blood. read more

Price

on

Request

Please View Probably The Best Selection Of Original & Varied Samurai Arms in Europe & Possibly the World

Please View One of The Best Selections Of Original Samurai Arms to be Seen. Over the past 49 years I have personally supervised our company's determination to provide the most interesting, educational, yet not too intimidating, gallery of original Japanese Samurai weapons, helmets, sword fittings, polearms, muskets and armour. Principally concentrating on swords and daggers, with a combination of age, beauty, quality and history. Thanks to an extensive contact base [built up over the past 100 years or more] that stretches across the whole world, including collectors [both large and small], curators, academics and consultants, we have been very fortunate, that this effort has rewarded us with the ability to offer, what we believe to be, the most comprehensive selection available in Europe, if not the world, and during that time we have handled likely tens of thousands of original samurai artefacts and swords. In one week I sent over 300 samurai swords and daggers to be sold at our business in Georgia, USA [in the 1970’s we found the best market for Japanese swords was America]. Some of the most learned scholars studying this art all their lives often only scratch the surface of the knowledge to be learnt in this field, and like them, we have always loved the incredible history of the Samurai, and admired, respected and envied the unparalleled quality and beauty of their swords. Our Japanese weapons vary in age up to 800 years old, and are frequently some of the finest examples of specialist workmanship ever achieved by mankind. We have tried to include, within the description of some items, a brief history lesson, for those that are interested, and may not know, that will describe the eras, areas and circumstances in which these items were used. We have tried our utmost to be informative and interesting without being too academic in order to keep the details vibrant, fascinating yet not too complex. Please enjoy, with our compliments, our Japanese Gallery. It has been decades in the creation, and we intend it to remain interesting and informative, hopefully, for decades to come. Although they appear to be likely a relative expensive luxury compared to other antique swords from other nations, they are in fact incredible value for money, for example a newly made bespoke samurai style sword blade from Japan will cost, today, in excess of £11,000, take up to two years to complete, will come with no fittings at all, and will be modern [naturally] with no historical context or connection to the ancient samurai past in any way at all. Our fabulous original swords can be many, many, hundreds of years old, stunningly mounted as fabulous quality works of art, and may have been owned and used by up to 30 samurai in their working lifetime. Plus, due to their status in Japanese society, look almost as good today as the did possibly up to 500 years ago, or even more. Mark Hawkins [Partner]. read more

Price

on

Request

A Shinto [1596-1781] Iron Tsuba Katana Guard With Brass Mimi

Chisseled with scrolling chanels and a kozuka ana and kogai ana. The oviod tsuba has [south fitted] copper kuchi-beni. The copper plug of the nakago-ana. Their function is to secure the tsuba firmly when mounted on a blade. These plugs are sometimes called sekigane. 2.75 inches across, 3 inches high read more

375.00 GBP

A Japanese Chisa Katana by Master Smith Hoki no kami Fujiwara Hirotaka

This is a delightful sword that would make a superb start to any fine collection of antique weaponry, a future heirloom for generation to come. It has a superb Japanese elegance in its quiet traditional samurai simplicity. Its overall condition and appearance is very fine indeed and would complement any elegant décor or surroundings.

Signed blade under the hilt tsuka, Hoki no kami Fujiwara Hirotaka

A highly rated early Shinto master smith Hoki no Kami Fujiwara Hirotaka was working in 1655 at Echizen province.

He was very skilful swordsmith most highly rated, and was making his swords like this one in the Kanemoto style.

Hirotaka was part of the so-called Echizen Shimohara Ha. Circa 1655, His working date, according to Fujishiro is Meireki period (1655-57) and he rates Hirotaka blades as ‘wazamono’ for their incredible sharpness and Chujosaku. Fujishiro states first he had the title of Hoki (no) Daijo and Hoki (no) Kami as in this example. He continues to state his work is similar to that of Harima Daijo Shigetaka and that these smiths co-operated in gassaku work. The blade is in around 90 to 95% of its original condition Edo polish, and very nice indeed with just a few surface marks. All the fittings are original Edo era, and are decorated with sea shell designs, and an o-sukashi deeply pierced Higo tsuba is Koto period, circa 1500. The chisa katana was able to be used with one or two hands like a katana (with a small gap in between the hands) and especially made for double sword combat a sword in each hand. It was the weapon of preference worn by the personal Samurai guard of a Daimyo Samurai war lord clan chief, as very often the Daimyo would be often likely within his castle than without. The chisa katana sword was far more effective as a defence against any threat to the Daimyo's life by assassins or the so-called Ninja when hand to hand sword combat was within the castle structure, due to the restrictions of their uniform low ceiling height. But in trained hands this sword would have been a formidable weapon in close combat conditions, when the assassins were at their most dangerous. The hilt was usually around ten to eleven inches in length, but could be from eight inches or up to twelve inches depending on the Samurai's preference. Chisa katana, Chiisagatana or literally "short katana", are shoto mounted as katana. It is fair to say wakizashi are shoto which are mounted in a similar way to katana, but in this instance we are considering the predecessors of the daisho. In the transitional period from tachi to katana, katana were called "uchigatana", and shoto were referred to as "koshigatana" and "chiisagatana", in many cases quite longer than the later more normal length wakizashi. A blade of this quality reflects the status of the lord or prince whose life it defended. The saya is in delightful quality high-polish finished traditional lacquer, with just slight age markings from the previous century. The saya is of original age so it displays a very slight element of looseness caused by hundreds of blade withdrawals, made in its lifetime. Overall 35 inches long, blade tsuba to tip 22.25 inches, tsuka 9.5 inches long. read more

Price

on

Request

![A Shinto [1596-1781] Iron Tsuba Katana Guard With Brass Mimi](photos/22652t.jpg)