Beautiful ‘Queen Anne’, London, Dragoon Officer's Long Barrel Horse Pistol, Lock Named James Barber A Most Beautiful Example.

12 inch Barrel, bearing early barrel proof stampings of A.R., the crossed sceptre gunsmith proof markings of Queen Anne, 1702-1714, stamped in the early period position, at the top of the breech of the barrel. Later on, and henceforth, proof marks were stamped on the left hand side of the breech. The pistols military furniture is all brass, with a typical officer's type short eared style skull crusher butt cap terminating with a grotesque mask the early type, from the time of King William IIIrd, before the long spurred style became fashionable in the 1740's. The lock is the early banana form, typical of the earliest 18th century long pistols, with a the good and clear name of Mr. Barbar inscribed. It has a good and responsive action. The stock is fine walnut. It has a single ramrod pipe, also typical of the early Queen Anne style. This would not be a trooper's pistol, but a officer's private purchase example, from one of the great makers and suppliers to the dragoon regiments and officers of his day, during the time of King George IInd. This pistol would have seen service during the War known as King George's War of 1744-48, in America, and the 7 Years War, principally against the French but involving the whole of Europe, and once again, also fought in America. Recognized experts like the late Keith Neal, D.H.L Back and Norman Dixon consider James Barbar to be the best gun maker of his day. Dixon states, "Almost without exception, unrestored and original antique firearms made by James Barbar of London are of the highest quality". In Windsor Castle there are a superb pair of pistols by James Barbar and a Queen Anne Barbar pistol also appeared in the Clay P. Bedford exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Barbar supplied complete dragoon pistols for Churchill's Dragoons in 1745, also guns for the Duke of Cumberland's Dragoons during 1746 to 48, and all of the carbines for Lord Loudoun's regiment of light infantry in 1745.

James was apprenticed to his father Louis Barbar in October of 1714. Louis Barbar was a well known gun maker who had immigrated to England from France in 1688. He was among many Huguenots (French Protestants) who sought refuge in England after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685. Louis was appointed Gentleman Armourer to King George I in 1717, and to George II in 1727. He died in 1741 .

James Barbar completed his apprenticeship in 1722 and was admitted as a freeman to the Company of Gunmakers. By 1726 James had established a successful shop on Portugal Street in Piccadilly. After his father's death in 1741, James succeeded him as Gentleman Armourer to George II, and furbisher at Hampton Court. He was elected Master of the Gunmakers` Company in 1742. James Barbar died in 1773.

The book "Great British Gunmakers 1740-1790" contains a detailed chapter on James Barbar and many fine photographs of his weapons. This lovely pistol is 19 inches long overall. It has had some past overall service restoration within the past 100 years. The mainspring, stock were replaced, as was the ramrod. But, it is often the case as this pistol may likely have seen somewhat rigorous combat service during its working life for upwards of 80 years. It is a beautiful looking pistol, and a fine looking example of the early British military pattern gunsmiths. As with all our antique guns no license is required as they are all unrestricted antique collectables read more

5850.00 GBP

A Fabulous Royal Bronze Battle Mace From 2,500 to 3,200 Years Old. From the Era of Rameses the Great of Egypt, to Darius, King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire. As Used By The Shardanas Warriors from Sardinia Who Fought for Rameses II Against the Hittite

13th-6th century BC. This is a classic style royal baton mace head of the ancient Bronze Age culture. Examples of this mace can be seen in several of the world's finest ancient Near Eastern bronze collections. The shaft is elaborately decorated with raised striking knobs of a herringbone design. This was an effective striking weapon likely used by high-ranking soldiers or royal subjects due to its extremely decorative design. In battle, maces like this were often used by commanders to display rank when giving orders in battle and leading soldiers, inspiring leadership and power. A substantial bronze cudgel and mace with tubular body, ribbed collar, flared rim and panels of raised herringbone ornament. Ist to 2nd Millennium B.C. In use it would have slotted onto a wooden haft. Items such as this were oft acquired in the 18th century by British noblemen touring the Middle East, Northern France and Italy on their Grand Tour. Originally placed on display in the family 'cabinet of curiosities', within his country house upon his return home. A popular pastime in the 18th and 19th century, comprised of English ladies and gentlemen traveling for many months, or even years, throughout classical Europe, and the Middle East, acquiring antiquities and antiques for their private collections. The use of the stone headed mace as a weapon and a symbol od status and ceremony goes back to the Upper Palaeolithic stone age, but an important, later development in mace heads was the use of metal for their composition. With the advent of copper mace heads, they no longer shattered and a better fit could be made to the wooden club by giving the eye of the mace head the shape of a cone and using a tapered handle.

Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded as the greatest, most celebrated, and most powerful pharaoh of the New Kingdom, itself the most powerful period of Ancient Egypt.

The Shardanas or warriors from Sardinia who fought for Ramses II against the Hittities were armed with maces, exactly as this fabulous example, consisting of rounded wooden hafts with the bronze mace heads slotted upon the hafts. Many bronze statuettes of the times show Sardinian warriors carrying swords, bows and original maces.

Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his death in 486 BCE. He ruled the empire at its territorial peak, when it included much of Western Asia, parts of the Balkans (Thrace–Macedonia and Paeonia) and the Caucasus, most of the Black Sea's coastal regions, Central Asia, the Indus Valley in the far east, and portions of North Africa and Northeast Africa including Egypt (Mudrâya), eastern Libya, and coastal Sudan.

Darius ascended the throne by overthrowing the legitimate Achaemenid monarch Bardiya, whom he later fabricated to be an imposter named Gaumata. The new king met with rebellions throughout his kingdom and quelled them each time; a major event in Darius' life was his expedition to subjugate Greece and punish Athens and Eretria for their participation in the Ionian Revolt. Although his campaign ultimately resulted in failure at the Battle of Marathon, he succeeded in the re-subjugation of Thrace and expanded the Achaemenid Empire through his conquests of Macedon, the Cyclades and the island of Naxos as well as the sacked Greek city of Eretria.

Persians used a variety of maces and fielded large numbers of heavily armoured and armed cavalry (cataphracts). For a heavily armed Persian knight, a mace was as effective as a sword or battle axe. In fact, Shahnameh has many references to heavily armoured knights facing each other using maces, axes, and swords. The enchanted talking mace Sharur made its first appearance in Sumerian/Akkadian mythology during the epic of Ninurta. Roman though auxiliaries from Syria Palestina were armed with clubs and maces at the battles of Immae and Emesa in 272 AD. They proved highly effective against the heavily armoured horsemen of Palmyra. Photos in the gallery of original carvings from antiquity in the British Museum etc.; Ashurbanipal at the Battle of Til-Tuba, Assyrian Art / British Museum, London/ 650-620 BC/ Limestone,, An Assyrian soldier waving a mace escorts four prisoners, who carry their possessions in sacks over their shoulders. Their clothes and their turbans, rising to a slight point which flops backwards, are typical of the area; people from the Biblical kingdom of Israel, shown on other sculptures, wear the same dress, on a gypsum wall panel relief, South West Palace, Nimrud, Kalhu Iraq, neo-assyrian, 730BC-727BC.

A recovered tablet from Egypt's Early Dynastic Period (3150-2613 BC) shows a Pharaoh smiting his foe with a war mace. Part of an original collection we have just acquired, of antiquities, Roman, Greek, Middle Eastern, Viking and early British relics of warfare from ancient battle sites recovered up to and around 220 years ago.

Last picture in the gallery; Ramses II A larger-than-life Ramses II towering over his prisoners and clutching them by the hair. Limestone bas-relief from Memphis, Egypt, 1290–24 BCE; in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity.

This wonderful piece would have been made and traded throughout the Western Asiatic region. 551 grams, 24cm (9 1/4"). read more

1750.00 GBP

Original 1930’s Third Reich Portrait of Rudolf Jordan Hitler's Personally Appointed Gauleiter of Halle-Merseburg & Magdeburg-Anhalt and Former General of the SA, Gruppenfuhrer der SA. Likely Commissioned & Paid For By Adolf Hitler Personally

Most rare surviving example of the official portrait of one of Hitler’s personally appointed district political leaders known as a Gauleiter, as almost all of around 450 original, 1930’s German portraits of Hitler’s inner circle and high command are now in the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington. Each portrait could have cost up to 12,000 Reichmarks each, a most considerable sum in 1939 around 60,000 dollars

Hitler usually bought and paid for them all personally, and the small Zinc bust of Rudolf Jordan by Albert Gottlieb he bought and paid 2000 Reich Marks for it in 1941 {about $10,000 US at the time} it's in the Deutsches Historisches Museum.

Approximately 114 men held the highly esteemed position of Gauleiter. Many shared a common background. Most of them, particularly during the early years, were drawn from the cadre of "old fighters" that had helped Hitler forge the Party during the Kampfzeit (Time of Struggle). The rank and power of these men was shared equally and was only four below Hitler himself. Their power was thus highly significant within the echelons of the Third Reich.

Many of these portraits were either commissioned, or acquired by Hitler personally, and they are all part of the record of Hitler and his elite commanders rise to power, in order to satisfy his determination to conquer the world and subjugate and destroy all who resisted.

No dictator can effectively govern a nation on his own. This was certainly the case with Adolf Hitler who had little time for or interest in the day-to-day regional administration of the Nazi Party.

For that purpose, he appointed his most loyal, charismatic and brutal subordinates: the ‘Little Hitlers’, officially known as Gauleiters.

Firstly, after the NSDAP gained power over Germany the Nazi Party adopted a new framework, which divided Germany into regions called Gaue. Each Gaue had its own leader, a Gauleiter. Each Gaue was then divided into subsections, called Kreise. Each Kreise then had its own leader, called a Kreisleiter. Each Kreise was then divided into even smaller sections, each with its own leader, and so on. Each of these sections were responsible to the section above them, with Hitler at the very top of the party with ultimate authority.

As almost all these oil portraits of Germany’s ‘Little Hitler’s’ were removed from Germany in 1945/6 and transported to America, it is estimated that just a very few, perhaps as few as between five or ten remained in Europe and in private hands. This is one of those tiny few. An incredibly rare example of the original, historical, visual record of the power structure organised by Hitler himself. Which makes this an incredibly rare original artifact that is an historically important representation of likely the most important and radical political events of the past thousand years. From those three decades of the 20th century that has changed the very structure of the world for all time.

The US high command in 1945/6 realised just how important it was to keep and save as many such portraits of his gauleiters as possible, as a permanent record and reminder for the future, of the monumental fight and sacrifices in order to subdue the axis powers from their schemes of world domination, during the two most significant decades of the past 300 years..

This is original portrait, in oil on canvas, of Gauleiter Rudolf Jordan (21 June 1902 - 27 October 1988). He was a Nazi Gauleiter in Halle-Merseburg and Magdeburg-Anhalt during Hitler’s socialist Third Reich. One of the notorious and prominent high command of Hitler’s Third Reich. An original Nazi oil portrait from the 1930's. Most similar in the new Aryan style of the Nazi portrait painter Fritz Erler, and his painting of 'Minister and Gauleiter Adolf Wagner', 1936. It was exhibited in the GDK, the Great German Art Exhibition, in 1939, in room 23. It was bought there by Hitler for 12.000 RM. In fact he bought two paintings by Fritz Erler: Portrait des Staatsministers und Gauleiters Adolf Wagner and Portrait des Reichsministers Fricke.

They are now in the possession of the US Army Military Center of History. Possibly this portrait was also in that exhibition with the two other Gauleiter Wagner and Frick. Erlers similar style portrait of Hitler, also painted in his SA uniform, in 1931, is currently valued for sale at 725,000 Euros. Around 450 portraits depicting Hitler and other Nazi-officials and symbols are currently stored in the U.S. Army Center of Military History in Washington

From 19 January 1931, Jordan was appointed Nazi Gauleiter of Halle-Merseburg, and then began rising within the Party ranks, acting as member of the Prussian Landtag between April 1932 and October 1933 and being appointed to the Prussian State Council and made an SA Gruppenfuhrer. In the same year began the publication of the Mitteldeutsche Tageszeitung newspaper, led by Jordan. In March 1933 came his appointment as Plenipotentiary for the Province of Saxony in the Reichsrat and in November 1933 his election as a member of the Reichstag. On 20 April 1937, Adolf Hitler personally appointed him Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) in Braunschweig and Anhalt and NSDAP Gauleiter of Magdeburg-Anhalt. Jordan was succeeded as Gauleiter of Halle-Merseburg by Joachim Albrecht Eggeling.

In the same year came Jordan's promotion to SA-Obergruppenfuhrer. In 1939, Jordan became Chief of the Anhalt Provincial Government and Reichsverteidigungskommissar (Reich Defence Commissar, or RVK) in Defence District XI. On 18 April 1944 came Jordan's last leap up the career ladder when he was appointed High President (Oberpresident) of the Province of MagdeburgIn the war's dying days, Jordan managed to go underground with his family under a false name. He was nonetheless arrested by the British on 30 May 1945, and in July of the next year, the Western Allies handed him over to the Soviets. Late in 1950 after four years in custody in the Soviet occupation zone Jordan was sentenced to 25 years in a labour camp in the Soviet Union. Only Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer's visit to Moscow managed to persuade the Soviets to reconsider Jordan's sentence, and then he was released on 13 October 1955. In the years to come, Jordan earned a living as a sales representative, and worked as an administrator for an aircraft manufacturing firm. He died in Munich. The Gardelegen massacre was the cold-blooded murder of inmates that had been evacuated from the Dora-Mittelbau concentration camp and some of its sub-camps on April 3rd, 4th and 5th. Around 4,000 prisoners had been bound for the Bergen-Belsen, Sachsenhausen or Neuengamme concentration camps, but when the railroad tracks were bombed by American planes, they had been re-routed to Gardelegen, which was the site of a Cavalry Training School and a Parachutist Training School. The trains were forced to stop before reaching the town of Gardelegen and some of the escaped prisoners had terrorized the nearby villages, raping, looting and killing civilians.

The man who is considered to be the main instigator of the Gardelegen massacre is 34-year-old Gerhard Thiele , who was the Nazi party district leader of Gardelegen. On April 6, 1945, Thiele called a meeting of his staff and other officials at which he issued an order, which had been given to him a few days before by Gauleiter Rudolf Jordan , that any prisoners who were caught looting or who tried to escape should be shot on the spot. In 1932, Nazi Gauleiter Rudolf Jordan claimed that SS Security Chief Reinhard Heydrich was not a pure "Aryan". Within the Nazi organisation such innuendo could be damning, even for the head of the Reich's counterintelligence service. Gregor Strasser passed the allegations on to Achim Gercke who investigated Heydrich's genealogy. Gercke reported that Heydrich was "... of German origin and free from any coloured and Jewish blood". He insisted that the rumours were baseless. Even with this report, Heydrich privately engaged SD member Ernst Hoffman to further investigate and deny the rumours. The last two pictures in the gallery of Jordan with Hitler and his Gaulieters at his 50th birthday examining his convertible Volkwagen Beetle, and the Erler painting of Gauleiter Wagner, bought by Hitler. 2 foot x 3 foot unframed. Water stain at the rear of the canvas. Surviving original portraits of Third Reich leaders are now very rare for at the end of the war thousands of paintings, portraits of Nazi-leaders, paintings containing a swastika or depicting military/war sceneries were destroyed. With knives, fires and hammers, they smashed countless sculptures and burned thousands of paintings. However around 8,722 artworks were shipped to military deposits in the U.S. From 1933 to 1949 Germany experienced two massive art purges. Both the National Socialist government and OMGUS (the U.S. Military Government in Germany) were highly concerned with controlling what people saw and how they saw it. The Nazis eliminated what they called Degenerate art, erasing the pictorial traces of turmoil and heterogeneity that they associated with modern art. The Western Allies in turn eradicated Nazi art. Whatever one considers about the actions of all of the entire third reich, art is art, and every piece is a representation of a portion of history, good or bad. One thing we learned very well from the tragic 1930s and 1940s is that classifying art as non-art and forbidding books or art for political reasons is a dead-end street. No matter how much one dislikes or despises the infamous despots and dictators of history, such as Hitler, Caligula, Pol Pot & Stalin, and no matter how much their depictions were used as propaganda, a painting or sculpture of them cannot be re-classified as 'non art'. This painting depicts a member of Hitler’s notorious inner circle, that for a brief period of world history very nearly placed the entire world in subjugation to the will of Germany and it’s ally Japan. It is the embodiment of why the preservation of such art can remind the thousands of its observers, for generations to come, that those people such as Rudolf Jordan, who were just ordinary looking nondescript individuals, that if left unchecked would have condemned the entire world to a nightmarish dystopia, of slavery, starvation and misery. And thanks to great leaders such as Winston Churchill, who had the talent and skill to embolden a solitary nation, racked by trepidation, facing the free world’s greatest foe alone, they were utterly routed and deposed by the near defeated and subdued great democracies. Part of the theory of Hannah Ahrend Johanna "Hannah" Arendt, 14 October 1906 - 4 December 1975 was a German-born Jewish American political theorist. Though often described as a philosopher, she rejected that label on the grounds that philosophy is concerned with "man in the singular" and instead described herself as a political theorist because her work centres on the fact that "men, not Man, live on the earth and inhabit the world." This portrait would nicely improve with some cosmetic restoration and cleaning. read more

4950.00 GBP

A Very Fine & Most Beautiful 18th Century Royal Naval Officer’s Sword of Hunting Sword Cutlass Type. As Used By Ship's Captain's and Fleet Admirals

Gilt brass hilt with fluted wooden grip and finely engraved blade with maker mark and Solingen, and hunting scenes.

Quillon block decorated with relief hunting horn and hunting devices. Acorn finials and fluted brass pommel.

In the days of the early Royal Navy, officers carried short swords in the pattern of hunting sword cutlasses, with both straight or curved blades, fancy brass mounted single knucklebow hilts with principally stag horn or reeded ebony grips. Although initially designed to protect the huntsman from a close quarter predatory attack, or the coup de grace, they were far more popular in England for use as naval officer's swords, not as their initial design intended, as Britain had far fewer great wild beasts that might threaten a huntsman.

There are numerous portraits in the National Portrait Gallery and The National Maritime Musuem that show British Admirals such as Benbow and Clowdesly Shovel holding such swords, often originally made on the continent as was this beauty.

24.5 inches long overall. read more

18th Century 1770's Hallmarked Silver Hilted American Revolutionary War Period Officer's Sword Used By Both American and British Officers. Made by William Kinman of London

A fabulously intricate pattern of hilt with a complex geometric piercing with arabesque scrolling and cut stone patterning. It is sometimes referred to as the Boulton pattern, named after Matthew Boulton a renown London silversmith of the 18th century. The grip has silver banding interspersed with a herringbone pattern twisted silver wire. William Kinman was a leading member of the Founders Company of London was born in 1728 and is recorded as a prominent silver hilt maker. He is recorded at 8 Snow Hill for the last time circa 1781, is recorded circa 1728-1808, [see L. Southwick 2001, pp. 159-160.]. The small sword or smallsword is a light one-handed sword designed for thrusting which evolved out of the longer and heavier rapier of the late Renaissance. The height of the small sword's popularity was between mid 17th and late 18th century. It is thought to have appeared in France and spread quickly across the rest of Europe. The small sword was the immediate predecessor of the French duelling sword (from which the épée developed) and its method of use—as typified in the works of such authors as Sieur de Liancour, Domenico Angelo, Monsieur J. Olivier, and Monsieur L'Abbat—developed into the techniques of the French classical school of fencing. Small swords were also used as status symbols and fashion accessories; for most of the 18th century anyone, civilian or military, and with gentlemanly status would have worn a small sword on a daily basis.

The small sword could be a highly effective duelling weapon, and some systems for the use of the bayonet were developed using the method of the smallsword as their foundation, (including perhaps most notably, that of Alfred Hutton).

Militarily, small swords continued to be used as a standard sidearm for infantry officers. In some branches with strong traditions, this practice continues to the modern day, albeit for ceremonial and formal dress only. The carrying of swords by officers in combat conditions was frequent in World War I and still saw some practice in World War II. The 1913 U.S. Army Manual of Bayonet Drill includes instructions for how to fight a man on foot with a small sword. Small swords are still featured on parade uniforms of some corps.

As a rule, the blade of a small sword is comparatively short at around 0.6 to 0.85 metres (24 to 33 in), though some reach over 0.9 metres (35 in). It usually tapers to a sharp point but may lack a cutting edge. It is typically triangular in cross-section. This sword's blade is approx 33 inches long. I its working life the pierced oval guard has been damaged, re-affixed and repaired

A sword by this maker with a very similar hilt is preserved in the Royal Armouries Leeds, IX.3782. See Southwick 2001, p. 290-1 pls. 75-7

read more

2295.00 GBP

A Beautiful, Signed Samurai Long 17th Century Katana With Very Fine Edo Period Mounts Including Fabulous Quality Hand Chisselled Silver Fuchi Kashira of Takebori Turbulent Seas and Sea Shells. Signed Hisamichi

The sword has just returned from our Japanese, trained polisher, for a final hand conservation and it look simply fabulous.

Its fabulous munuki are bound underneath the micro woven plaited tsuka-ito hilt binding, depict takebori gold and shakudo Mount Fuji, and a man running in the waves that are before Mount Fuji. The saya is black urushi lacquer with a carved buffalo horn kurigata and brown sageo wrap. The blade shows a beautiful notare based on suguha hamon, with fine hada. The nakago is signed and bears the signature, Omi no Kami Hisamichi, but not, or very unlikey to be one of the four Mashina school masters, also named Hisamichi.

Very fine signed iron plate hira-kaku-gata tsuba, but when mounted, the tsuba seppa-dai is covered by seppa (metal spacers) and the signature (mei) is not visible as usual. With a mimi {a prominant rim} and a kozuka hitsu-ana, and kogai hitsu ana, and very scarcely seen, twin holes near the rim at the bottom of the tsuba called ude-nuki ana. These represent the sun and moon and were likely used for threading a leather wrist thong to prevent dropping the sword in battle on horseback, and to tie the tsuka to the saya.

The name katana derives from two old Japanese written characters or symbols: kata, meaning side, and na, or edge. Thus a katana is a single-edged sword that has had few rivals in the annals of war, either in the East or the West. Because the sword was the main battle weapon of Japan's knightly man-at-arms (although spears and bows were also carried), an entire martial art grew up around learning how to use it. This was kenjutsu, the art of sword fighting, or kendo in its modern, non-warlike incarnation. The importance of studying kenjutsu and the other martial arts such as kyujutsu, the art of the bow, was so critical to the samurai a very real matter of life or death that Miyamoto Musashi, most renowned of all swordsmen, warned in his classic The Book of Five Rings: The science of martial arts for warriors requires construction of various weapons and understanding the properties of the weapons. A member of a warrior family who does not learn to use weapons and understand the specific advantages of each weapon would seem to be somewhat uncultivated. European knights and Japanese samurai have some interesting similarities. Both groups rode horses and wore armour. Both came from a wealthy upper class. And both were trained to follow strict codes of moral behaviour. In Europe, these ideals were called chivalry; the samurai code was called Bushido, "the way of the warrior." The rules of chivalry and Bushido both emphasize honour, self-control, loyalty, bravery, and military training.

Samurai have been describes as "the most strictly trained human instruments of war to have existed." They were expected to be proficient in the martial arts of aikido and kendo as well as swordsmanship and archery---the traditional methods of samurai warfare---which were viewed not so much as skills but as art forms that flowed from natural forces that harmonized with nature.

Some samurai, it has been claimed, didn't become a full-fledged samurai until he wandered around the countryside as begging pilgrim for a couple of years to learn humility. When this was completed they achieved samurai status and receives a salary from his daimyo paid from taxes (usually rice) raised from the local populace.

Blade 28.3 inches long, tsuba to tip. read more

7255.00 GBP

A Most Attractive 500 Plus Year Old Samurai Battle Katana With All Original Edo Mounts,

Shibui mounted in all its original Edo period mounts and saya. Higo iron fushigashira mounts, decorated with takebori gold aoi leaves. Tetsu round tsuba with pierced kozuka and [gilt copper filled] kogai hitsu-ana. The original Edo saya lacquer is simply beautiful, in two shades of black with an intricate fine rainfall pattern within the design. The menuki under the Edo silk binding, are patinated takebori flowers with pure gold highlights. The blade has a beautiful undulating hamon pattern of considerable depth.

Shibui is a term that effectively translates to ‘quiet’ , it is a reference to a sword that has a relatively subdued look as it concentrates on high quality yet subtle elegance, as it is a sword entirely concentrating on combat and less on flamboyant display. Of course all samurai swords were designed for combat, often despite being mounted as works of art, often with fantastic quality fittings worthy of Italian Renaissance jewels, such as the European equivalent work by the Italian master Cellini, but they would be for samurai eager to display their status in the elite hierarchy of the samurai class, such as daimyo. The swords mounted shibui were for the samurai of far more serious nature, dedicated to their more basic standards of bushido, the art of the ultimate warrior, with little or no interest in displays of rank. A samurai of the highest skill but preferring the anonymity of almost being invisible to unwanted attention.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu [to stop the spear] exanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesised in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality. The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday and was also a painting master. Members of a hierarchal class or caste, samurai were the sons of samurai and they were taught from an early age to unquestionably obey their mother, father and daimyo. When they grew older they may be trained by Zen Buddhist masters in meditation and the Zen concepts of impermanence and harmony with nature. The were also taught about painting, calligraphy, nature poetry, mythological literature, flower arranging, and the tea ceremony. 40 inches long overall. 28.5 inch long blade, from tsuba to tip., The blade is in super condition for its age, with just a few wear marks, and pit marks on the mune back edge near the boshi. The saya lacquer has some natural age craking at the base read more

6450.00 GBP

A Fine & Beautiful Museum Piece. An Original Antique Fijian Ula, A Throwing War Club. A Singularly Beautiful Example & of Exceptional Rarity, From A Fijian Warring Cannibal Tribe Circa 18th Century Lt. Bligh RN of the Mutiny On The Bounty Period

A handsomely hand carved hardwood throwing club "ula" showing a stunning natural, age patina. With fine globed assymetrical head with top knob, and geometric carved patterning on the haft. It is perhaps the most famous and recognizable of all oceanic weapons.

The ula was the most personal fighting war weapon of the Fijian warrior and was carried, inserted into a warrior’s fibre girdle sometimes in pairs like pistols.

The throwing of the ula was achieved with great skill, precision and speed. It was often carried in conjunction with a heavier full length club or spear which served to finish an opponent after initially being disabled by a blow from the ula. It was made by a tribal weapon specialist from a variety of uprooted bushes or shrubs.

Across 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from east to west, Fiji has been a nation of many languages. Fiji's history was one of settlement but also of mobility. Over the centuries, a unique Fijian culture developed. Constant warfare and cannibalism between warring tribes were quite rampant and very much part of everyday life. During the 19th century, Ratu Udre Udre is said to have consumed 872 people and to have made a pile of stones to record his achievement."Ceremonial occasions saw freshly killed corpses piled up for eating. 'Eat me!' was a proper ritual greeting from a commoner to a chief.

The posts that supported the chief's house or the priest's temple would have sacrificed bodies buried underneath them, with the rationale that the spirit of the ritually sacrificed person would invoke the gods to help support the structure, and "men were sacrificed whenever posts had to be renewed" . Also, when a new boat, or drua, was launched, if it was not hauled over men as rollers, crushing them to death, "it would not be expected to float long" . Fijians today regard those times as "na gauna ni tevoro" (time of the devil). The ferocity of the cannibal lifestyle deterred European sailors from going near Fijian waters, giving Fiji the name Cannibal Isles; as a result, Fiji remained unknown to the rest of the world.

According to Fijian legend, the great chief Lutunasobasoba led his people across the seas to the new land of Fiji. Most authorities agree that people came into the Pacific from Southeast Asia via the Malay Peninsula. Here the Melanesians and the Polynesians mixed to create a highly developed society long before the arrival of the Europeans.

The European discoveries of the Fiji group were accidental. The first of these discoveries was made in 1643 by the Dutch explorer, Abel Tasman and English navigators, including Captain James Cook who sailed through in 1774, and made further explorations in the 18th century.

Major credit for the discovery and recording of the islands went to Captain William Bligh who sailed through Fiji after the mutiny on the Bounty in 1789.

The first Europeans to land and live among the Fijians were shipwrecked sailors and runaway convicts from the Australian penal settlements. Sandalwood traders and missionaries came by the mid 19th century.

Cannibalism practiced in Fiji at that time quickly disappeared as missionaries gained influence. When Ratu Seru Cakobau accepted Christianity in 1854, the rest of the country soon followed and tribal warfare came to an end.

Trade of sandalwood was the dominant feature of the opening of markets between Europeans and the islands, and the finest early Fijian weaponry likely came to Europe from the earliest maritime visitors in the 18th century to early 19th century.

This Ula would likely have been made and used at the time of Lt Bligh and his journey upon HMS Bounty.

'A Chart of Bligh's Islands Fiji by William Bligh. The Broken Line shows my Track in the Bounty's Launch when I discovered the Islands in 1789. The Plain Line my Track in the Providence and Assistant in 1792. The parts tinged Green were seen in the Bounty's Launch.' Added and inscribed in pencil on the left is 'Land seen by the ships Hope and Ann -Captain Maitland, 1799'. Made in ink and pencil on tracing paper, dated 14 April 1801. See Bligh's chart in the gallery

The Ula is approx 13 inches long read more

1750.00 GBP

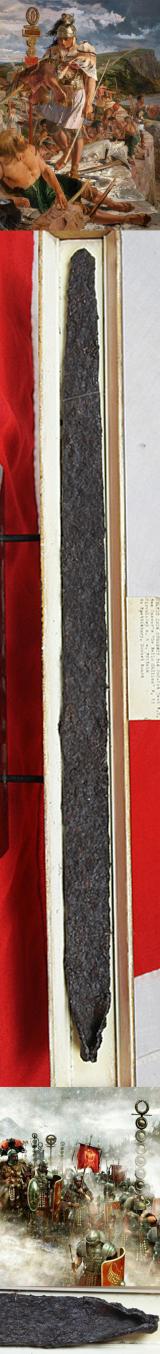

Incredibly Rare British Celtic Iron Age Sword Circa Ist Cent. BC. Made Around a Century Before the Roman Conquest, by Claudius. Amazingly Its Very Type Was Noted in Caeser's Writings During His Time In Britannia. A Durotriges Celts Sword. Discovered 1857

According to the British Museum, who have an extremely similar example, there are only a few hundred remaining in existence today in the world. All of those that have been discovered, have been uncovered from famous hordes or individual finds, usually in South Central England within the past 200 years or so. This sword would have been used around what is being referred to as 'Duropolis', after the Ancient Briton, Celt, Durotriges tribe, which existed in the Wessex region. In its prime, it is thought to have contained 'hundreds' of inhabitants and would have been a major trading centre for southern Britain. The previously unknown habitation in Winterborne Kingston, near Blandford, dates from around 100BC, which makes it 80 years earlier than Colchester in Essex. Colchester was previously widely regarded as Britain's oldest recorded town.

Another fabulous hoard of around 800 Celtic iron age artefacts were announced just a few days ago in March 2025, from the Brigantes Celts of the 1st century B.C.

The most famous of the Ancient Briton Celtic tribes were the Iceni {whose name might have come from Iken, the original name of the River Ouse, where the tribe are said to have come from} who had settlements across Norfolk, in North Suffolk and East Cambridgeshire. One of them was at Brettenham on the Peddars Way, east of Thetford, which was built by Romans to quickly transport troops up to The Wash and Brancaster, where they had a fort protecting North Norfolk.

Queen Boudicca of the Iceni, probably the most famous of all the ancient Celts waged war against the Romans in Britain from 60 AD after the Romans decided to rule the Iceni directly and confiscated the Norfolk property of the leading tribesmen. The uprising was motivated by the Romans' failure to honour an agreement they had made with Boudica's husband, Prasutagus, regarding the succession of his kingdom upon his death, and by the brutal mistreatment of Boudica and her daughters by the occupying Romans.

this amazing sword is formerly from the ex-museum collection with their labelling on its display mounting board, this Ancient Briton sword was also used as a currency bar and is from the Dorset Hoard, an Iron Age hill Fort, in Dorset, excavated in 1857. It is acknowledged that this incredible and significant piece is one of the earliest examples of ancient British currency, utilizing sword blades, it is thought currency bars in the form of swords are actually the very first form of currency used in the British Isles around 2000 to 2,100 years ago, and used to barter and trade all manner of goods, and highly prized as of exceptional value at the time. It is a form of currency that is actually mentioned in Julius Caeser's writings, following Julius Caesar's expeditions to the island of Britannia in 55 and 54 BC. An Iron Age Celtic Dorset Hoard Sword, 2nd-1st century BC. It is further believed by some that they were money in the form of a sword as they were indeed once a functional sword, that was retired from combat.

A substantial long blade with the original short folded-over handle to one end; displayed in an old custom-made box housing with a recently added base and bearing old typescript 'CELTIC IRON 2nd-1st Cent B C / See Caesar's 'De Bello Gallico' V, 12 / Circulated s. and w. Britain / Dorset Hoard' label in four lines with inked correction to Spetisbury. including case (30 inches). Fair condition, held in an old museum display case with identification label.

Provenance

Ex Dorset, UK, hoard, found 1857; accompanied by a copy of the Archaeological Journal 96, pp.114-131, which includes details for the find.

Literature for reference.

See Gresham, Colin A., Archaeological Journal 96, pp.114-131, which includes details for this and other finds from the site; see also Smith, Reginald, Currency Bars, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, London, 2nd Series, XX, p.182 for comparison between the examples; cf. British Museum, accession no.1862,0627.18 for an example from the site (acquired from J. Y. Akerman in 1862; other items were acquired in 1892 from the Durdan, Blandford collection). The name Brittannia was predominantly used to refer simply to the island of Great Britain. After the Roman conquest under the Emperor Claudius in AD 43, it came to be used to refer to the Roman province of Britain (later two provinces), which at one stage consist of part of the island of Great Britain south of Hadrian's wall. Almost every weapon that has survived today from this era is now in a fully russetted condition, as is this one, even the very few swords of kings, that have been preserved in national or Royal collections are today still in a relatively fair condition, but they are from a much later period.

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity read more

2495.00 GBP

Possibly The Finest 17th Cent. French Royal Silver Hunting Short Sword, With Original, Incredibly Rare Scabbard & Belt Mount, From a Royal Collection. With The Rarest Bayonne Form Hilt. Likely Used By The King & His Court For the King’s Boar or Stag Hunt

This is a superb French King Louis XIVth royal hunting all silver mounted short sword, and all silver mounted scabbard, and the sword hilt has a hunting carbine muzzle form bayonne hilt, that can, once fitted into the guns barrel, enable the sword to be used as the very first form of bayonet, that converts a carbine into a long pike or spear. In fact the hilt form was named after the French town of Bayonne, where it was said to have been first used, and thus technically invented, and it is the very first form of bayonet ever made, and whence every future bayonet therefore gets its name. It is fitted within its incredibly rare original silk and silver bullion baldric, and we have never seen another surviving original example of such a fabulous royal baldric outside of Les Invalides Museum in Paris. There may possibly be another in the British {H.M. King Charles IIIrd’s } Royal Collection, as it is likely the largest in the world, but we have never seen it. Silk is one of the worlds strongest natural materials, stronger than steel pound for pound, in fact bullet proof vests were originally made from densely woven silk, but once very old, it becomes fragile and therefore antique silk rarely survives intact, especially such a piece as this.

It further bears in silver bullion decor, stitched into the baldric silk belt ‘frog’ mount, behind the two retaining cross straps, twin, inverted and elongated capital letter ‘L’s’, the personal cypher mark and symbol of King Louis XIVth of France.

The highly distinctive cypher mark of all the King’s of France bearing the name Louis. This may very likely indicate that this sword-bayonet was actually owned and used by the King or within the service of the King of France, by one of his highest ranking officers, or indeed an officer of his personal guard, while in use at the French royal hunting lodge by the king, or his entourage of the Royal Court, for hunting boar or stag.

The hunting sword is only usually used as the ‘coup de grace’ to finish off the beast at the hunts conclusion. However it is also an essential defensive arm to protect the king or a noble if the beast turns upon its hunter, which can be most perilous, and indeed, it is well known to be a most frequent fate of many unfortunate huntsman. The royal hunt since medieval days has been a very dangerous royal sport, with many nobles, princes or even kings meeting their grisly end.

King William II (William Rufus), who reigned in England from 1087 to 1100, was killed by an arrow while hunting in the New Forest on August 2nd, 1100, a death widely suspected to be an assassination rather than a hunting accident

King Christian V died from the after-effects of a hunting accident that occurred on October 19, 1698. Christian was hunting with his two sons and his half-brother.

One of finest quality pieces of its type we have ever had the privilege to own, and incredibly still in its original silver mounted scabbard and silk and silver bullion baldric. Probably this can be seen as the best available within the worldwide collecting market today.

It is also probably the most complete example, from the mid to late 1600's, we have ever seen, certainly in over 40 years, including those we have handled within the Royal Collections. This magnificent hunting short sword with bayonne {bayonet} hilt would be the prize of any of the finest worldwide collections of the rarest short swords that can double as the very rare, so called ‘plug’ bayonet, as they are ‘plugged’ into the muzzle of a musket, to convert it to a pike or spear. It is remarkably complete with its silver bullion and silk baldrick frog belt mount with three tongues. It has finest quality solid silver mounts, with decorated quillons bearing profile heads of possibly the king’s huntsman adorned with hunting caps, very similar to the armourer's marks on the blade. And the silver scabbard mounts and fittings also beautifully match, with an acorn frog mount. The original scabbard leather is superb condition, crosshatch patterned, with the so called ‘bullets and lines’ stamped decor. It has a wonderful blade, in stunning order, with two large matching armourer's marks of a profile head on both blade sides. The grip handle is birds-eye maplewood with a silver pommel.

While en residence at Versailles, at 2 pm: the king, Louis XIVth, gave his orders and announced his plans in the morning. If he went on a walk, it would be in the gardens on foot or in a Barouche with the ladies. If he decided to go hunting, the favourite sport of the Bourbons, the monarch would go to the park if he chose to hunt with weapons, and to the surrounding forest when hunting on horseback.

Since the days of the Pharoahs, hunting has been an essential activity of courts. Hunting was both a pleasure, and a way of gathering game for the royal table. Once one area was hunted out, the court moved on to the next. In many different monarchies hunting became an obsession, with its own music, dress and flamboyant rituals. One Chinese prince said: ‘I would rather not eat for three days than not hunt for one’

Hunting was so important that it could decide where the court resided. The proximity of hunting forests was one reason for the choice, as a royal residence, of Windsor, Versailles, Stupinigi, Hubertusberg, and many other sites. Conversely, the choice of these sites as royal residences ensured that the surrounding forests were well maintained. The landscape of the Ile de France is still dominated by the royal hunting forests of Versailles, Marly, Saint-Germain, Compiegne, Vincennes, Fontainebleau, and Rambouillet.

In addition to the pleasure and food it provided, hunting could also acquire a political and hierarchical function. Hunting was a visible assertion of domination over the land and the animal kingdom. It also protected the ruler’s subjects and their herds from boar, wolves and other vermin. The stag was the noblest beast, hunting it the noblest sport. Furthermore hunting was believed to be a school of war, masculinity and horsmanship. It taught courage, comprehension of landscape, and the art of the cavalry charge. In l’Ecole de Cavalerie of 1751, Robichon de La Guerroniere described hunting:

‘it is the pastime which Kings and Princes prefer to all others. This inclination is no doubt based on the conformity existing between hunting and war. In both, in effect, there is an object to tame’,

The story of the evolution of the bayonne, plug bayonet;

The late 17th century saw the final demise of the pike, and its replacement by the bayonet. The plug bayonet, which blocked the muzzle of the musket and needed to be removed for firing, did not catch on. The earliest military use of bayonets was by the French Army in 1647, at Ypres. These were plug-fitted into the barrel. That prevented firing once they were mounted, but allowed musketeers to act as their own pikemen, which gave infantry formations greater firepower. By 1650 some muskets had bayonets fixed to the gun at manufacture, hinged and foldable back along the barrel. French fusiliers adopted the plug bayonet as standard equipment in 1671; English fusiliers followed suit in 1685. The trouble with firing in successive lines was that it was only practical on a narrow front. In open country, the musketeers could easily be flanked, especially by cavalry. In most battles, the musketeers relied on pikemen to protect them while reloading. Infantry practiced various formations and drills that allowed musketeers to hide behind the pikes while reloading and to take up firing positions as soon as their weapons were ready to use. This system worked pretty well, but it obviously cut down the army’s firepower-sometimes by more than half.

The solution to the problem was to turn the musket into a spear. According to some sources, this was the idea of Sebastien le Prestre de Vauban, the great French military engineer in the armies of Louis XIV. It was a solution at least for soldiers. Hunters in France and Spain had for some time been jamming knives into the muzzles of their muskets for protection against dangerous game. It seems that Bayonne, a French city noted for its cutlery, made a type of hunting knife that was favoured for this use. When the French army adopted this weapon, it was called a ‘bayonet’. The earliest reference to the use of the bayonet is in the memoirs of a French officer who wrote that on one campaign, his men did not carry swords, but knives with handles one foot long and blades of the same length. When needed, the knives could be placed in the muzzles of the guns to turn them into spears. The bayonet proved to be a much more effective defense against cavalry than the sword.

There were some drawbacks to the use of plug bayonets when mounted in muskets, When the bayonet was inserted within in the muzzle of a loaded musket and then fired by accident, the gun might indeed explode. This sort of accident seems to have been much more prevalent among civilians who, unlike soldiers, did not load and fire on command. It was so prevalent that in 1660, Louis XIV had to issue a proclamation forbidding the placing of short sword-daggers in the muzzles of hunting guns.

Two pictures in the gallery are of French royal hunts, note in picture 9 the king is holding aloft his same hunting short sword with its distinctive curved blade, and his mistress armed with a boar spear. read more

7950.00 GBP