Antique Arms & Militaria

A Superb US 'Wild West' Period Marlin Fire-Arms Co. Lever Action Repeating Rifle Manufactured in 1883. Nr. Exactly As Used By Apache Indian Fighter Brig. Gen. George C. Crook. A Superior Gun Compared To The Winchester Lever Repeater.

A very rare and good all original Marlin .40-60 lever action repeating rifle. Model 1881 in an obsolete calibre.

This has a very good rifle indeed and has gathered a beautiful patina. Serial no. 4456, for 1883. octagonal barrel, the top-flat signed ‘MARLIN FIRE-ARMS CO. NEW-HAVEN C.T. USA’ over patent dates to ‘1880’, dove-tailed fore-sight, elevating buckhorn rearsight, slab-sided receiver with sliding load gate and top ejection.

Bolt with integral dust-cover walnut butt-stock and fore-end and full-length under-barrel magazine, overall length 45.5in., weight approx

According to Flayderman’s Guide To Antique American Firearms, “The Model 1881

was years ahead of the Model 1886 Winchester, and proved a very popular rifle.”

In October 1881, the Miles City, Montana Territory, gun dealer Broadwater, Hubbell

& Co. advertised that a case of the Model 1881 Marlins had already been sold to “Hunters,” adding that, “these guns promise to be very popular and take preference over all others.” In March 1882, another of their advertisements lauded

the Model 1881: “The New Buffalo Gun. A large Stock on hand, of various weights,

from 8 to 16 lbs., from which to make selection. These are THE Buffalo Gun.” In 1882 other dealers—such as W.H. Bradt in Leadville, Colo., and C.D. Ladd in San Francisco—were also advertising the Model 1881. The Marlin Company itself promoted the Model 1881 in July 1885 in Denver’s Rocky Mountain News as “The Best In The World.” And in April 1889, Marlin advertised in the Sitka Alaskan, “The Best And Simplest Rifles Made, Strongest Shooting, Easiest Working.”

Apache Indian fighter Brig. Gen. George C. Crook, who coined the frontier axiom that “the only way to catch an Apache is with another Apache,” used a Model 1881 Marlin. Crook spent most of his military career trying to placate, instead of kill, renegade Indians from the Pacific Northwest to the central Plains. But he is most famous for bringing a semblance of peace to the Apache-ravaged southeast corner of Arizona Territory in the 1870s and again in the 1880s at a time when another frontier axiom was “the only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

One of the rifles that Crook passed down to his godson, Webb C. Hayes (son of President Rutherford B. Hayes), is a Model 1881 Marlin, serial number 4254. It was Webb Hayes’ favourite rifle on hunting trips with his godfather. The gun now resides in the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Center in Fremont, Ohio.

Mickey Free, (part Mexican, Irish and Apache) one of Crook’s most trusted Apache-wars Indian scouts, is also known to have favoured a 'brass-tack Indian-decorated' Model 1881 Marlin, which is now in the private collection of the Frontier Gun Shop in Tucson, Ariz.

On January 27, 1861, Apache Indians had kidnapped 12-year old Free from the ranch of his stepfather, John Ward, near Sonoita, Arizona Territory. The incident sparked the killing of Apache prisoners by the U.S. Army and white prisoners by the Apaches and drove Chief Cochise on a bloody warpath until 1872. Blinded in the left eye when he was young, the reddish blond–haired Free was raised by White Mountain Apaches.

Free joined the U.S. Army’s Indian Scouts on December 2, 1872, and served with them until 1893.

A .40-60-calibre Model 1881 Marlin that was used by Oklahoma Territory outlaw “Red Buck” Waightman is now on display at the Ralph Foster Museum, College of the Ozarks, Point Lookout, Mo.

In spite of the Model 1881 repeating rifle’s reputation for quality and simplicity, John Marlin discontinued it in 1892 after having produced only about 20,000 of

them.

Section 58 (2) antique / obsolete calibre no licence required to own and collect/display read more

Italian Hunting Dagger, Republic of Genoa, Ligurian 17th - 18th Century. Spiral Twist Carved Multi Coloured Horn with Silver Inserts. Blade with Baluster Shaped Forte Of A Finely Engraved Ricasso, Two Symmetrical Edges To The Tip.

Just returned from a no expense spared museum grade expert hand polishing and cleaning conservation in the workshop.

This Italian hunting dagger has a long history. Its shape and engraved blade type is typical of the Genoa region, and it can be dated to the 17th and 18th century. This dagger was likely used for more than a century

This is the typical blade of Ligurian daggers. It begins with a baluster-shaped part, ricasso, and continues by two symmetrical cutting edges up to the tip.

On the ricasso, there is a deeply engraved bird of paradise decoration, the central spine has fine line ribbon form engraving which continues up to around half of the blade.

These intriguing and most attractive daggers were produced in Italy, Sardinia and Spain from the late 17th to the 18th century.

17th-century Ligurian daggers, often stilettos or parrying daggers (like the main-gauche), were used by civilians for self-defense and by gentlemen as a fashion accessory and tool, while specific types like the swordbreaker were for dueling and others were favored by the lower classes. The exact usage and user depended on the dagger's specific style and design, such as its lethality, ornamentation, or utility. Daggers were an important part of everyday dress and could enhance apparel, with more lavishly decorated daggers carried by the gentry and aristocracy.

The blade has a few minuscule edge to edge combat contact marks, and tip has a very slight inward curve.

9 inches long overall. read more

1195.00 GBP

A Superb & Rare French Modele 1733-1766 Flintlock Pistol, Manufactured For The King of France, King Louis XVIth, For the American Revolutionary War Supply, To Aid General Washington's Forces in 1776

We were thrilled to acquire a pair of these most rare pistols {to be sold separately, and the first we listed is now sold} The first of the pair was dated 1776, this example is undated, just as was the other very rare identical example sold at Rock Island Auction in the USA, in 2020 for $7,475.

Manufactured at Maubeuge, with M. Maubeuge Manufacture signed lock, and interior lock stamp P.G. the monogram of the nom de maitre platineur

A most rare and superb example of the form of pistol made in France in 1776 for King Louis XVI of France and supplied to the armed forces of the United States Continental Congress, for the use of General George Washington's revolutionary rebel forces in 1776, and also for use for the French volunteer regiments that fought in America. France, at first surreptitiously, and later, less covert, gave America over 5 billion livres in aid and materials, weapons, men and ammunition. However, as it was effectively never actually repaid, it resulted in the ruination of the French economy, which led to the French Revolution, and thus the fall of the monarchy, and execution of the King and Queen France, King Louis and Marie Antoinette, as well as most of the French aristocracy that didn’t have the foresight to switch loyalties {during 'The Great Terror'}. Plus, after Americas successful victory, France, not entirely surprisingly, expected preferential trade deals and treaties with the new United States of America, by way of thanks, which failed to materialise, in fact it was far worse for France, as a very advantageous trade deal and treaty was in fact struck instead, between Britain and America. It’s strange that things often never quite turn out how one might imagine, but it shows how it is not a modern phenomenon, that politics can turn things completely on its head, and ones bitterest enemies can become ones most welcome allies in just a matter of a few months.

French involvement in the American Revolutionary War of 1775–1783 began in 1776 when the Kingdom of France secretly shipped supplies to the Continental Army of the Thirteen Colonies when it was established in June 1775. France was a long-term historical rival with the Kingdom of Great Britain, from which the Colonies were attempting to separate.

A Treaty of Alliance between the French and the Continental Army followed in 1778, which led to French money, matériel and troops being sent to the United States. An ignition of a global war with Britain started shortly thereafter. Subsequently, Spain and the Dutch Republic also began to send assistance, which, along with other political developments in Europe, left the British with no allies during the conflict (excluding the Hessians). Spain openly declared war in 1779, and war between British and Dutch followed soon after.

France's help was a major and decisive contribution towards the United States' eventual victory and independence in the war. However, as a cost of participation in the war, France accumulated over 1 billion livres in debt, which significantly strained the nation's finances. The French government's failure to control spending (in combination with other factors) led to unrest in the nation, which eventually culminated in a revolution a few years after the conflict between the US and Great Britain concluded. Relations between France and the United States thereafter deteriorated, leading to the Quasi-War in 1798.

France bitterly resented its loss in the Seven Years' War and sought revenge. It also wanted to strategically weaken Britain. Following the Declaration of Independence, the American Revolution was well received by both the general population and the aristocracy in France. The Revolution was perceived as the incarnation of the Enlightenment Spirit against the "English tyranny." Ben Franklin traveled to France in December 1776 in order to rally the nation's support, and he was welcomed with great enthusiasm. At first, French support was covert. French agents sent the Patriots military aid (predominantly gunpowder and weapons) through a company called Rodrigue Hortalez et Compagnie, beginning in the spring of 1776. Estimates place the percentage of French-supplied arms to the Americans in the Saratoga campaign at up to 90%. By 1777, over five million livres of aid had been sent to the American rebels.

A painting in the gallery is of Washington and Lafayette. The Marquis De Lafayette was a french volunteer who joined Washington's General Staff. Lafayette was wounded at Brandywine, the first battle in which he fought for the American cause. While recuperating, he wrote to his wife, “Do not be concerned, dear heart, about the care of my wound…. When he Washington sent his chief surgeon to care for me, he told him to care for me as though I were his son, for he loved me in the same way.” Washington and Lafayette fought side by side in several other battles.

Overall in excellent condition, good crisp action.

A near identical, rare, undated example of this pistol, that only bears its model number 1763, was sold at an American Auction, Rock Island Auction in September 2020 for $7,475. https://www.rockislandauction.com/detail/80/3089/french-navy-model-176366-flintlock-pistol read more

A Stunning & Rare 5th Royal Irish Lancers Tchapka Helmet Plate

In superb condition, fabulous bronze patina and two helmet screw posts. Battle honours up to the Boer War. King Edward VIIth's crown. The regiment was originally formed in 1689 as James Wynne's Regiment of Dragoons. They fought in the Battle of the Boyne and at the Battle of Aughrim under William of Orange. Renamed the Royal Dragoons of Ireland, they went on to serve with the Duke of Marlborough during the Spanish War of Succession and earned three battle honours there.In 1751, they were retitled 5th Regiment of Dragoons and in 1756 the 5th (or Royal Irish) Regiment of Dragoons. As such, they served in Ireland and were active during the Irish Rebellion of 1798. However, they were accused of treachery; their accusers claimed their ranks had been infiltrated by rebels. (According to Continental Magazine, April 1863, the unit refused to attack a group of rebels.) This accusation appears to have been false, but nevertheless they were disbanded at Chatham in 1799. The regiment was reformed in 1858, keeping its old number and title, but losing precedence, being ranked after the 17th Lancers. It was immediately converted into a lancer regiment and titled 5th (or Royal Irish) Regiment of Dragoons (Lancers). In 1861, it was renamed the 5th (or Royal Irish) Lancers and then the 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers. The regiment served in India and a section served in Egypt in 1885, taking part in the battles at Suakin. It served with distinction in the Second Boer War from 1899 to 1902, gaining battle honours at Battle of Elandslaagte and The Defence of Ladysmith.

The regiment then returned to England where it stayed until the outbreak of World War I, when it became part of the British Expeditionary Force and saw action continually from 1914 to 1918 in some of the war's bloodiest battles. During the battle of Bourlon Wood George William Burdett Clare received the Victoria Cross posthumously. The 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers won a total of 20 battle honours during the Great War.

The 5th (Royal Irish) Lancers also has the grim honour of being the regiment of the last British soldier to die in the Great War. This was Private George Edwin Ellison from Leeds, who was killed by a sniper as the regiment advanced into Mons a short time before the armistice came into effect.

The regiment was renamed 5th Royal Irish Lancers and disbanded in 1921, but a squadron was reconstituted in 1922 and immediately amalgamated with the 16th The Queen's Lancers to become the 16th/5th Lancers The Royal Irish Lancers were in Mons at the time of retreat in 1914 but escaped and returned on Armistice Day. The last cavalry regiment out and the first back!. The memorial panel we show in the gallery records the return welcomed by the Maire and the Cur?. The scene is taken from a painting, ?5th Lancers, Re-entry into Mons?, last heard of in the private collection of a Belgian citizen. This in turn is almost a mirror image of a painting ?5th Lancers, Retreat from Mons? (whereabouts unknown). In the former, the troopers are heading in the opposite direction to the ?Retreat?, and a middle-aged priest and a pregnant woman watching the departure of the regiment among a worried-looking crowd of Belgian citizens have subtly changed: the priest is now white-haired and the mother holds up her four-year-old child, having lived through the occupation of the German forces in Mons for four years. The Great War 1914

The 5 Lancers, as part of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, were heavily involved and played a major role in the initial mobile actions fought by the BEF. They gained the distinction of being the last cavalry regiment to withdraw from Mons during the retreat; they also had the privilege to be the first British regiment to re-enter Mons after the pursuit in November 1918. Generally the First World War is described as a war of trench deadlock primarily fought by the infantry, gunners and engineers, this assessment is correct. It must however be remembered that cavalry regiments were expected to take their place in the line from time to time and did share the privations of trench warfare suffered by the infantry. On a number of occasions 5 L particularly distinguished themselves: in the defence of Guillemont Farm, June 1917, 3 MCs, and 4 MMs were won and during the defence of Bourlon Wood in 1918 Private George Clare won a posthumous VC. While the main focus of the First World War remained with the armies fighting on the western front it was by no means the only theatre of war. In 1918 Allenby, a 5th Lancer and later a Field Marshal, reorganised British forces in the Middle East pushing his lines forward into northern Palestine. Allenby's Army broke through at Megiddo resulting in the collapse of Turkish resistance. 8.25 inches x 5 inches approx. read more

225.00 GBP

A Superb, Victorian, Scottish Lord Lieutenant's Belt Plate and Silver Bullion, Belt and Sword Straps. Queen Victoria's Personal Representative in Scotland When She Was Not Available

Belt. Silver bullion belt backed with morocco leather, silver scrolling thistle pattern to the silver lace brocade belt. Since 1831 this has been analogous to the uniform worn by a General Staff Officer, but with silver lace in place of the gold worn by Regular General officers. The Lord-Lieutenant is the British monarch's personal representative in each county of the United Kingdom. Historically, the Lord-Lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. Lieutenants were first appointed to a number of English counties by King Henry VIII in the 1540s, when the military functions of the sheriff were handed over to him. He raised and was responsible for the efficiency of the local militia units of the county, and afterwards of the yeomanry, and volunteers. He was commander of these forces, whose officers he appointed. These commissions were originally of temporary duration, and only when the situation required the local militia to be specially supervised and well prepared; often where invasion by Scotland or France might be expected.

Lieutenancies soon became more organised, probably in the reign of his successor King Edward VI, their establishment being approved by the English parliament in 1550. However, it was not until the threat of invasion by the forces of Spain in 1585 that lieutenants were appointed to all counties and counties corporate and became in effect permanent. Although some counties were left without lieutenants during the 1590s, following the defeat of the Spanish Armada, the office continued to exist, and was retained by King James I even after the end of the Anglo-Spanish War.

The office was abolished under the Commonwealth, but was re-established following the Restoration under the City of London Militia Act 1662, which declared that:

The King's most Excellent Majesty, his Heirs and Successors, shall and may from Time to Time, as Occasion shall require, issue forth several Commissions of Lieutenancy to such Persons as his Majesty, his Heirs and Successors, shall think fit to be his Majesty's Lieutenants for the several and respective Counties, Cities and Places of England and Dominion of Wales, and Town of Berwick upon Tweed.

Although not explicitly stated, from that date lieutenants were appointed to "counties at large", with their jurisdiction including the counties corporate within the parent county. For example, lieutenants of Devon in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries appointed deputy lieutenants to the City of Exeter, and were sometimes described as the "Lieutenant of Devon and Exeter" The origin of this anomaly may have lain in the former palatine status of Pembrokeshire.

The City of London was uniquely given a commission of lieutenancy, and was exempt from the authority of the lieutenant of Middlesex. The Constable of the Tower of London and the Warden of the Cinque Ports were ex-officio lieutenants for the Tower Hamlets and Cinque Ports respectively, which were treated as counties in legislation regarding lieutenancy and militia affairs.

The official title of the office at this time was His or Her Majesty's "Lieutenant for the county of ..", but as almost all office-holders were Peers of the realm, they were referred to as "Lord-Lieutenant". read more

325.00 GBP

A Very Rare, Solid Silver, Long Distance Flight, Aeronautical Medal, Major von Parseval 1909, awarded For the Flight of The Parseval Dirigible Airship In October 1909

Designed by world renown medalist Karl Goetz 1875 - 1950

Very Rare silver medal, for the flight of 12th to 19th October, 1909. Long-distance voyages of the Parseval airships. Half-length portrait of the airship designer A. Parseval to the left / eagle stands with outstretched wings on the bow of the airship, below water surface, above right inscription. Hallmark: 'feinsilber' BAYER. MAIN MINT OFFICE. a medal that was awarded in two grades, silver and bronze, this, the silver is an incredibly rare antique aviation medal from the earliest days of airships. August von Parseval (5 February 1861, in Frankenthal (Pfalz) – 22 February 1942, in Berlin) was a German airship designer.

As a boy, Von Parseval attended the Royal Bavarian Pagenkorps in Munich from 1873 to 1878, where he took the Fähnrichexamen (cadet exams). He then joined the Royal Bavarian 3rd Infantry Regiment Prinz Carl von Bayern. An autodidact, he busied himself with the problems of aeronautics. In the garrison town of Augsburg he came into contact with August Riedinger and also came to know his later partner Rudolf Hans Bartsch von Sigsfeld, with whom he developed Drachenballons: balloons used by the military for observation.

In 1901 Parseval and Sigsfeld began building a dirigible airship. After Sigsfeld's death during a free balloon landing in 1902, the work was interrupted until 1905.

By 1905, thanks to improvements in motor design, an appropriate engine was now available. His designs were licensed to the British Vickers company. Up to the end of the First World War, 22 Parseval airships (both non-rigid (blimps) and semi-rigid (with keels)) were built. In the late twenties and early thirties, four more semi-rigid airships were built in accordance with the "Parseval-Naatz principle". read more

675.00 GBP

A Beautiful 18th Century, London Marked, 1770's Brass Flintlock Blunderbuss Pistol, All Brass Mounted. By Renown Master Gunsmith Mr Joseph Bunney. A Stunning Rarity & A Museum Piece Worthy Example.

Royal Naval Captain's Pistol. The lock has a sliding safety is maker inscribed, and marked the top barrel flat at the breech end "LONDON" and made by a fine English maker, the left rear flat is marked with two regular crown over sceptre proofmarks. Fine quality rococo scroll floral engraving on the breech end of the barrel, trigger guard, buttcap and on the left side plate. All original wooden ramrod with swelled head and mounted with a full juglans regia walnut stock.

The brass has been lovingly polished over the past 250 years and has a superb and mellow natural age patina. There is light trace pitting on the frizzen. The stock has a similar fabulous naturally polished age patina, with a couple of very minor cracks on the rear of the lock. The markings are clear.

Rococo Style: His pieces often feature intricate, chiselled bas-relief scrollwork and floral patterns in the Rococo style.

High-Quality Construction: Bunney's work is noted for its superb quality, elegant proportions, and tasteful Georgian mountings.

His active period was approximately 1765 to 1814, and his surviving firearms, which include pocket pistols, coaching pistols, and repeating guns, are considered highly accomplished examples of the era.

A pair of his revolutionary war use pistols by Joseph Bunney are owned by the New Hampshire Historical Society in America, of General Joseph Cilley (1734-1799), of Nottingham, NH. A pair of pistols presented to him by the New Hampshire Assembly, March 16 or 19, 1779, by resolution "that the worthy Colonel Joseph Cilley be presented with a pair of pistols as a token of this State's intention toward merit in a brave officer." Colonel Cilley carried those pistols in the campaign against the Indians in New York, in which he was soon engaged (1779). The pistols were awarded for acts of bravery during the American Revolution.

These kind of all brass pistols were the weapon of choice for naval officers and ship's captains in the 18th century for use at sea. This is a superb example. The muzzle (and often the bore) was flared with the intent not only to increase the spread of the shot, but also to funnel powder and shot into the weapon, making it easier to reload in haste. The flared swamped muzzle is one of the defining features of this fabulous pistol. Ship's Captain's found such impressive guns so desirable as they had two prime functions to clear the decks with one shot, and the knowledge to an assailant that the pistol had the capability to achieve such a result. In the 18th and 19th century mutiny was a common fear for all commanders, and not a rare as one might imagine. The Capt. Could keep about his person or locked in his gun cabinet in his quarters a gun just as this. The barrel could be loaded with single ball or swan shot, ball twice as large as normal shot, that when discharged at close quarter could be devastating, and terrifyingly effective. Potentially taken out four or five assailants at once. The muzzle was swamped like a cannon for two reasons, the first for ease of rapid loading, the second for intimidation. There is a very persuasive psychological point to the size of this gun's muzzle, as any person or persons facing it could not fail to fear the consequences of it's discharge, and the act of surrender or retreat in the face of an well armed pistol such as this could be a happy and desirable result for all parties concerned.

French court gunsmith Marin le Bourgeoys made a firearm incorporating a flintlock mechanism for King Louis XIII shortly after his accession to the throne in 1610. However, firearms using some form of flint ignition mechanism had already been in use for over half a century. The development of firearm lock mechanisms had proceeded from the matchlock to wheellock to the earlier flintlocks (snaplock, snaphance, miquelet, and doglock) in the previous two centuries, and each type had been an improvement, contributing design features to later firearms which were useful. Le Bourgeoys fitted these various features together to create what became known as the flintlock or true flintlock.

The new flintlock system quickly became popular, and was known and used in various forms throughout Europe by 1630, although older flintlock systems continued to be used for some time. Examples of early flintlock muskets can be seen in the painting "Marie de' Medici as Bellona" by Rubens (painted around 1622-25). These flintlocks were in use for alongside older firearms such as matchlocks, wheellocks, and miquelet locks for nearly a hundred years. The last major European power to standardize the flintlock was the Holy Roman Empire, when in 1702 the Emperor instituted a new regulation that all matchlocks were to be converted or scrapped. The action is good. 9 inch barrel 15 inches long overall read more

2995.00 GBP

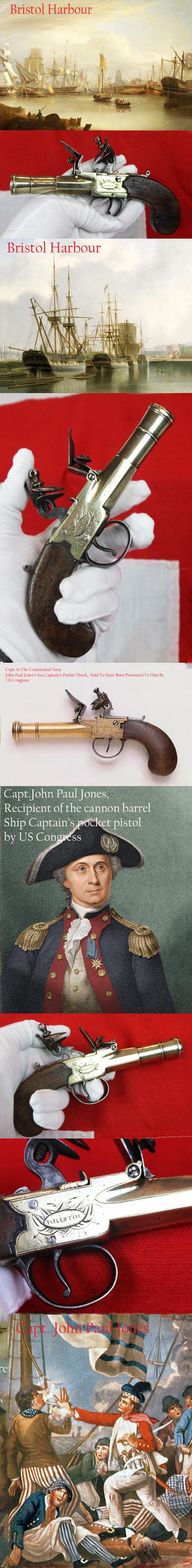

A Fabulous, 18th Century Sea Captain's Brass Cannon Barrel Pocket Blunderbuss Pistol. A Near Pair to the Pistol Presented To America’s Most Famous Revolutionary War Naval Commander John Paul Jones

This has to quite simply be one of the most beautiful and outstandingly attractive 18th century pocket pistol you will ever see.

A rare and and most fine original 18th Century Sea Captain's cannon barrel pocket Pistol, that is almost a pair to the John Paul Jones Sea Captain’s pistol presented to him by the 18th century American Congress

Brass cannon barrel flintlock pocket pistol, the barrel is three stage cannon barrel type, with a good working flintlock action, with sliding safety catch, maker marked by a fine maker, from a world renown English naval port and harbour, Bristol.

We show in the gallery a photograph of an almost identical brass cannon barrelled ships captain's pocket pistol in the Massachusetts Historical Society Museum Collection, a near pair to our pistol, that was said to have been presented by US Congress to John Paul Jones (1747-1792), a newly appointed captain in the Continental Navy, on October 10, 1776.

In many respects such a pistol was considered a symbol of rank and status in both the British and American navies, as it is said only the Captain would be permitted to carry such an arm on board, hence its presentation by Congress to Jones as a symbol of his command of a ship of the line in the US Navy.

As early as 1420, vessels from the English port Bristol were regularly travelling to Iceland and it is speculated that sailors from Bristol had made landfall in the Americas before Christopher Columbus or John Cabot. After Cabot arrived in Bristol, he proposed a scheme to the king, Henry VII, in which he proposed to reach Asia by sailing west across the north Atlantic. He estimated that this would be shorter and quicker than Columbus' southerly route. The merchants of Bristol, operating under the name of the Society of Merchant Venturers, agreed to support his scheme. They had sponsored probes into the north Atlantic from the early 1480s, looking for possible trading opportunities. In 1552 Edward VI granted a Royal Charter to the Merchant Venturers to manage the port.

By 1670, the city had 6,000 tons of shipping, of which half was used for importing tobacco. By the late 17th century and early 18th century, this shipping was also playing a significant role in British world trade.

John Paul was born near Kirkbean in Scotland to John Paul, Sr. and Jean McDuff. He first went to sea as an apprentice at the age of 13 and continued to work on merchant and slave ships as a young man. On a voyage aboard the brig John in 1768, both the captain and a ranking mate of his vessel died suddenly of yellow fever, and John Paul navigated the ship safely back to port. As a reward, the Scottish owners promoted him to master of the ship and its crew. Eventually he fled Scotland for North America to avoid charges of murder, due to his killing of a so-called mutineer in Tobago, and changed his name to John Paul Jones. He was assigned as a 1st Lieutenant in the newly-founded Continental Navy on 7 December 1775 and went on to become the first well-known naval commander in the Revolutionary War. He is sometimes referred to as the "Father of the American Navy". After a long career, including a stint in the Imperial Russian Navy, he died in Paris in 1792. During the American Revolution Capt John Paul Jones urged that “open and hostile operations” be utilised on any of “the Towns of Great Britain or the West Indies.” These targets, included the important ports of “London, Bristol, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh,” He suggested a brilliant US naval war strategy, in that he acknowledged that the US Continental Navy couldn't possibly defend the American ports and harbours against attack by the most superior Royal Navy. However, if the US Navy attacked the poorly defended enemy harbours and towns the Royal Navy would be forced to divert ships to defend all vulnerable British ports and thus keep those vessels away from the American harbours and coastal towns. In the gallery we show period paintings and engravings of Capt.Jones utilising his small box lock pistols in his numerous naval close combat assaults.

One interesting reveal as to Capt Jones character.

Before he fled England to avoid a murder charge he lived for some time in the sea port town of Whitehaven, where, apparently, the locals treated him well, and with the usual friendliness and courtesy as to expected. However some few years later, at 11 p.m. on April 22, 1778, Commander John Paul Jones led a small detachment of two boats from his ship, the USS Ranger, to raid the shallow port at Whitehaven, England, where, by his own account, 400 British merchant ships are anchored. Jones was hoping to reach the port at midnight, when ebb tide would leave the shops, that he intended to plunder, at their most vulnerable.

Jones and his 30 volunteers had greater difficulty than anticipated rowing to the port, which was protected by two forts. They did not arrive until dawn. Jones’ boat successfully took the southern fort, disabling its cannon, but the other boat returned without attempting an attack on the northern fort, after the sailors claimed to have been frightened away by a ‘noise’. To compensate, Jones set fire to the southern fort, which subsequently engulfed the town, and burnt much to the ground, rendering many of the townsfolk homeless and thus destitute. Some might say it is a most interesting way of repaying his historical debt of courtesy to the decent people of Whitehaven. However, it must be pointed out that legend has it that Capt. Jones was of a most chivalric character, and had many fine points, none the least of which was his much respected skill in his new tactics of attacking his former home in order to cause terror and fear to the people of England.

Benjamin Franklin fully agreed with Captain Jones new tactic of terror and fear warfare, but he considered he could not condone it officially, as he believed it would be most counter productive to appear that a new sovereign nation could be engaging in what we we would call today, terrorism. Political sensitivities were as much a part of life then as they are today, and were indeed over, say, two thousand years ago, or in fact, likely since the dawn of mankind, and whenever it was that for the very first time a stone age man began to consider what others would think of him or her, and how he or she was regarded by their neighbours.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery read more

2395.00 GBP

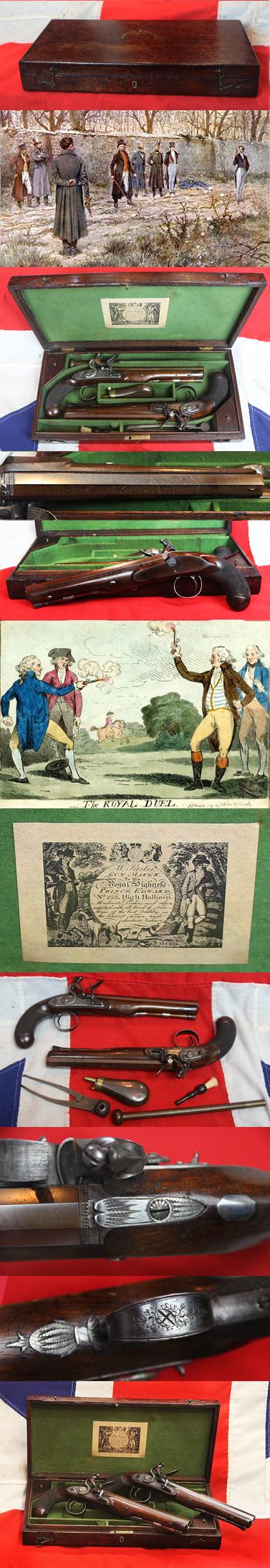

A Very Fine Condition Classic, Cased Pair of Late 18th to Early 19th Century Damascus Barrelled Duelling Pistols by Master Gunsmith William Parker of Holborn London. Original Oak Case with Tools and Accessories

More than two hundred years ago a bespoke cased pair of duelling pistols, with all its required tools, powder, flask, flints, and balls, contained within its hand made case was the privilege of the highest echelons of society, for gentlemen of the world, bearing great status and considerable worth. They were extraordinarily expensive in their day, as the very pinnacle of finest craftsmanship England that had to offer. Bearing in mind, England was at the apex of the world of manufacturing, creating all its products of the finest quality and the highest possible standard. The standard by which all other countries measured their abilities to produce, and where the term ‘Made in England’ represented the very best that money could buy.

And still today, a cased pair of finest English duelling pistols are at the very pinnacle of the world of antique collectors.

A superb original cased pair, in their original case, and near identical to, from the exact same design, pattern and form, as another very fine cased pair, also commissioned from William Parker, of London, that were formerly in the American Billionaire, J.P.Morgan’s, Family Collection, well over 100 years ago, and said to be his ‘pride and joy’

J. P. Morgan was a 19th century and early 20th century world renown American banker and philanthropist, he was subsequently categorised as America's greatest banker, who's reorganising skills and actions, in the great panic of 1907, saved America's monetary system

William Parker (1790-1841), produced some of Englands finest flintlock guns at 233 High Holborn London, from 1793-1839. Parker was Gun maker to the Duke of Kent, Prince Edward and King William IV.

Browned octagonal smooth 16 bore barrels are marked “London” on tops. Locks with waterproof pans, bridled roller frizzens, chamfered lockplates with rebated tails, and high breasted serpentine cocks, are fitted with sliding safeties, and are engraved with feather flourishes and “Parker” under pans on the lock face. traditional English style walnut stocks that have wraparound checkering with mullered borders on bag grips. “Stand of Arms”engraved trigger guards have stylized pineapple finials, and some original blueing. Stocks attach to the barrels with two sliding barrel slides, with no escutcheons. Horn tipped rosewood ramrods are held by two nicely filed, beaded, steel pipes. Both ramrods have steel, ball extractor worms. Original mahogany case has dual pivoting hook closure, and Parker's most distinctive inlet foldaway “D” handle. The interior is lined in traditional green pill-napped cloth, with W. Parker paper label on lid depicting pair of gentlemen gunners and their dogs. Case contains copper bag shaped powder flask, loading rod with mushroom tip, 1 cleaning brush. Covered compartments with turned brass knobs on covers, for the containing of flints and balls.

Excellent condition overall. Damascus twisted steel barrels in beautifully refreshed browning, Breech irons and locks retain a delightful patina. Trigger guards equally with nice patina. Stocks are excellent, retaining most of their original finish, edges and checkering sharp and very crisp, with a number of small use surface dents, handling marks, Bores are excellent. Locks and frizzens are crisp. Case is very fine retaining most of its original finish. Interior cloth is fine with light marks and soiling from contact with guns and accessories. Label is fine, slightly foxed and dented from contact with frizzen springs. Accessories are all fine, but incorrect mould, both pistols are 36 centimetres long overall, 23.4cm barrels, case size 21cm x 43.5 cm x 7.2 cm

William Parker was born to Thomas and Elizabeth in 1772, at Croscombe in Somerset. Nothing is known of his early years, but in 1792 the name William Parker appears in a Holborn rate book for the address of 233 High Holborn. This address had until the latter part of the eighteenth century been occupied by a John Field and his father–in–law John Clarke. Alongside his name in the rate book was that of ‘Widow Field’, a jeweller. At this time William was aged only 20 years and it is not fully understood under what pretext he started at this address. It is probable that he had been working at the location as an apprentice silversmith, as a business had operated there under the names of ‘Field & Clarke, silversmiths’ between the years 1784 and 1793.

The process of the name changing from Field and Clarke to William Parker started when John Field died around 1790. Entries with his name are recorded in the Holborn rate books from 1783 until 1790. In 1791 his name is still listed, but underlined and the word ‘Widw’ inserted. Records suggest John Clarke survived until at least May 1793, but it is probable he died around this time.

John Field’s marriage to Sarah Clarke had resulted in one surviving child, also called John born circa 1779 in the County of Middlesex. Following the death of John the elder William Parker married his widow Sarah on the 1 July 1792. It is not unusual for a new business to trade under an established name and this probably accounts for the name Field surviving in various forms for a few more years. Entries in trade directories confirm that by 1796-1797 William was operating under his own name as a sole trader, a situation that would continue until his death in 1841.

John Field the younger is often referred to as William’s ‘son-in-law’, but was in fact his step-son. In the nineteenth century the term ‘in-law’ meant related by marriage, but also extended to children, which is not the case now, when we would use the term step-son. William and Sarah appear to have had no other children, but John did marry and went on to have seven children of his own, three boys and four girls. The two eldest boys, John William Parker Field and William Shakespeare Field were to follow their father and grandfather’s trade as gun makers.

As a gun maker William Parker was a well known for producing a range of weapons from standard issue items to the finest duelling pistols. He later started to produce truncheons and other articles such as handcuffs, swords and rattles, and had the major contracts to supply arms and truncheons to the Metropolitan police of London.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of trading read more

13250.00 GBP

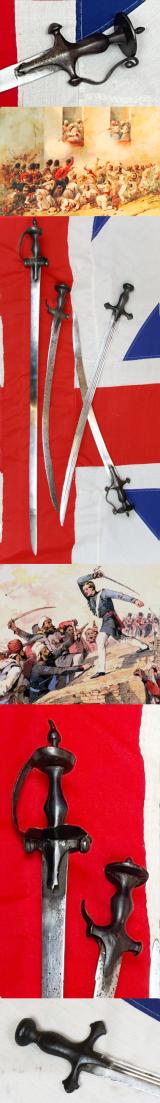

Just Arrived! A Superb, Small Collection of Early, & Historical 18th Century Indian Swords From the Siege and Relief Of Lucknow. Battle Trophies of an Irish Captain Of the 32nd Foot

The 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot played a key role in defending the Residency during the Siege of Lucknow in the Indian Mutiny (1857-1859). After the British annexation of Oudh, the 32nd's mess house, the Khursheed Manzil, was occupied by the regiment, which then helped fortify the Residency. Under Colonel John Inglis, the regiment held out for 140 days, winning four Victoria Crosses for acts of gallantry during the prolonged siege. The regiment was retitled the 32nd (Cornwall) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) in recognition of its heroic actions during the defense of Lucknow.

When the Indian Mutiny broke out, the 32nd Regiment of Foot was stationed at Lucknow and was a cornerstone of the British defence of the Residency.

The regiment's commander, Colonel John Inglis, took command of the garrison after the death of the Chief Commissioner, Sir Henry Lawrence.

The 32nd Regiment of Foot endured constant attacks, severe casualties from intense heat, and the ravages of cholera during the 140-day siege.

Gifted to the family by Irish born Capt. H.G.Browne {later Colonel of the 100th Foot} who died just before WW1 and was buried near his home on the Isle of Wight.

17th to 18th century Indian tulwar swords and a khanda, all to be sold seperately, however, some could make a fabulous display paired and crossed. some are in great condition, one has had its knuckle bow blasted in half, possibly by cannon shot, and one has so many combat sword cuts on its edge they are almost too numerous to count. A very impressive piece for the display of its historical context as a sword of battle.

First Siege

Full-scale rebellion reached Lucknow on May 30 and Lawrence was compelled to use the British 32nd Regiment of Foot to drive the rebels from the city. Improving his defenses, Lawrence conducted a reconnaissance in force to the north on June 30, but was forced back to Lucknow after encountering a well-organized sepoy force at Chinat. Falling back to the Residency, Lawrence's force of 855 British soldiers, 712 loyal sepoys, 153 civilian volunteers, and 1,280 non-combatants was besieged by the rebels.

Comprising around sixty acres, the Residency defenses were centered on six buildings and four entrenched batteries. In preparing the defenses, British engineers had wanted to demolish the large number of palaces, mosques, and administrative buildings that surrounded the Residency, but Lawrence, not wishing to further anger the local populace, ordered them saved. As a result, they provided covered positions for rebel troops and artillery when attacks began on July 1.

The next day Lawrence was mortally wounded by a shell fragment and died on July 4. Command devolved to Colonel Sir John Inglis of the 32nd Foot. Though the rebels possessed around 8,000 men, a lack of unified command prevented them from overwhelming Inglis' troops.

The sieges and reliefs of Lucknow cost the British around 2,500 killed, wounded, and missing while rebel losses are not known. Though Outram and Havelock wished to clear the city, Campbell elected to evacuate as other rebel forces were threatening Cawnpore. While British artillery bombarded the nearby Kaisarbagh, the non-combatants were removed to Dilkuska Park and then on to Cawnpore.

To hold the area, Outram was left at the easily held Alambagh with 4,000 men. The fighting at Lucknow was seen as a test of British resolve and the final day of the second relief produced more Victoria Cross winners than any other single day. Lucknow was retaken by Campbell the following March. read more

Price

on

Request