A Magnificent and Large Horse Mounted Samurai's Battle Sword Katana, With A Simply Stunning Shinto Blade In Near Mint Condition for Age. The Mounts Are All Completely Original Edo Period.

A beautiful substantial and impressive Bizen tradition war katana, with a very fine classic koshi no hiraita midare hamon. High-ranking warriors sword that were the only samurai permitted to fight on horseback.

Plain tettsu Higo school fuchi kashira in a traditional russet finish. Original Edo tsuka ito wrapped over ancient form menuki of russet iron spear heads, in early yari and naganata form. Round tetsu Higo schookl kinuki tsuba with two udenuki-no-ana. The holes being for the passage of a cord, tying the tsuba to the scabbard.

The saya is very fine, with a sayjiri bottom iron mount, with light ‘cinnabar pink’ urushi lacquer finish, also known as coromandel pink {named from the pink petaled flower} urushi lacquer to the saya, often made with the addition of perilla oil. The condition of both saya is very good just a couple of aged surface nicks

The colour created from urushi lacquer mixed with cinnabar was rewarded to them as the most famous warriors of all the samurai clans of Japan, the Li, and the Takeda.

Samurai endured for almost 700 years, from 1185 to 1867. Samurai families were considered the elite. They made up only about six percent of the population and included daimyo and the loyal soldiers who fought under them. Samurai means one who serves."

Samurai were expected to be both fierce warriors and lovers of art, a dichotomy summed up by the Japanese concepts of bu to stop the spear expanding into bushido (the way of life of the warrior) and bun (the artistic, intellectual and spiritual side of the samurai). Originally conceived as away of dignifying raw military power, the two concepts were synthesised in feudal Japan and later became a key feature of Japanese culture and morality. The quintessential samurai was Miyamoto Musashi, a legendary early Edo-period swordsman who reportedly killed 60 men before his 30th birthday.

In Japan the term samurai evolved over several centuries

In Japanese, they are usually referred to as bushi (武士,) or buke (武家). According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning 'to wait upon', 'accompany persons' in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean 'those who serve in close attendance to the nobility', the Japanese term saburai being the nominal form of the verb." According to Wilson, an early reference to the word samurai appears in the Kokin Wakashū (905–914), the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the first part of the 10th century.

Originally, the word samurai referred to anyone who served the emperor, the imperial family, or the imperial court nobility, even in a non-military capacity.It was not until the 17th century that the term gradually became a title for military servants of warrior families, so that, according to Michael Wert, "a warrior of elite stature in pre-seventeenth-century Japan would have been insulted to be called a 'samurai'".

This is a katana was likely made for a senior, high ranking samurai, a seieibushi. based upon horseback in combat, certainly not a light and deeply cursive katana, but a battle sword, made to complete an uncomprimising task of close combat and aggressive close quarter hand to hand swordmanship. Designed as much for cleaving through samurai armour and kabuto helmets in two, as much as defeating another samurai while on horseback. Although samurai would not, one would say, be a cavalry based warrior, all senior samurai would be mounted and thus travel on horseback, and some cavalry type samurai could be deployed in battle, but with differing combat styles depending on what part of Japan they came from. The cavalry troops, being Samurai, had personal retainers that stayed closer to them in the Sonae, carried their weaponry and worked as support units, much like an European squire. They also joined the fight whenever possible (especially in the mounted infantry scenario) and were often responsible of taking heads for their lords.

These foot Samurai were also used as heavy infantry or archers to support the ashigaru lines.

Tactics

Given the fact that the Samurai could directly dismount and operate as infantry, there were some specific tactics for horsemen.

Cavalry in general was only used after the battle was already started, either to deliver a decisive victory or to trying to save the day.

Norikiri

This is a classic charge, where several small groups of five to ten horseman ride consequently (possibly with a wedge formation) into a small area against the enemy lines, to maximize the shock. It was mainly used by heavy cavalry in the East, but given the fact that the ideal target where "weavering" units with low morale or disorganized, even medium cavalry could perform this charge.

The main role of this charge was to create confusion; if it didn't succeed, the cavalry regroups and either retreat or deliver another charge.

Norikuzushi

This is a combined infantry and cavalry charge. The horseman charged first, and after creating mayhem, a second charge is delivered by infantries armed with polearms, which could keep on fighting. The main target for this tactics were ranged units detached by the army. After a Norikuzushi usually follows a Norikiri by the cavalry group

30 inch blade overall 43 inches long in saya. read more

7250.00 GBP

A Superb, Original, 1879 Zulu War Small Cow-Hide Zulu Shield. Likely A Zulu Iwahu Shield. From the Time Of Islandwana, Rorke's Drift and Ulundi. Souvenir of the Zulu War

The ideal size for a historical display today, of a private collector or museum, such as combined with original Zulu War pieces, such as spears & knopkerrie {war clubs}.

Small cow-hide shields such as this were developed into larger versions, known as Isihlangu, in the early 19th century by Shaka kaSenzangakhona, a great warrior king and innovator who transformed Zulu warriors into a potent military machine. Shaka also introduced a new short, stabbing spear and a new style of fighting whereby the Zulu could barge his enemy off balance with the shield, or use it to hook around hid enemy's shield, pull it across his body and stab him under the left arm. These new weapons and methods, combined with tactical brilliance on the battlefield allowed the Zulu to conquer their neighbours, consolidate economic and military power, and resist European invasion for a long period.

The Zulu military system was based on the close bonding of unmarried men grouped by age. Brought together in a barracks at about 18-20 years old, a group of 350-400 men developed a strong identity as a 'regiment' or impi thanks to insignia such as the patterning on their shields. Each impi had its own kraal of cattle, and King Shaka assigned each a specific hide patterning. Impi kept their shields turned face-inwards under their arms while charging the enemy, until the last moment when the entire regiment turned their shields to face the enemy - who would only realise which of Shaka's regiments they faced with seconds to spare. This idea that the shield represented one's military identity is enshrined in the Zulu expression, "to be under somebody's shield", meaning to be under their protection.

Yet the different colours and markings on shields did more than just identify a specific impi. Great warriors had white shields with one or two spots, the young and inexperienced had black shields whilst the middle warriors had red shields. This demarcation formed the basis of the Zulu's famous battle formation imitating the horns, chest and loins of a cow, which is thought to have originated in hunting as a means of encircling game. During combat, the youngest and swiftest warriors, carrying dark shields, made up the 'horns', attempting to surround the enemy and draw him into the 'chest', whereupon the elite white shields would destroy him.

After a year of basic training, young warriors were sent home to tend their family cattle herds, mobilising for active service for four months of each year thereafter. Impi were disbanded when the men reached their late thirties and, under Shaka, it was only then they could marry. However, by the time of Zulu War of 1879, in the reign of Cetewayo, the marriage age was much younger and married warriors were no longer regarded as inferior and could bear a white shield in battle. Whether a Zulu warrior was active or retired, his shield remained an important symbol of his status upon entering marriage.

The Zulus, 22,000 strong, attacked the camp at Isandlwana and their sheer numbers overwhelmed the British. As the officers paced their men far too far apart to face the coming onslaught. During the battle Lieutenant-Colonel Pulleine ordered Lieutenants Coghill and Melvill to save the Queen's Colour—the Regimental Colour was located at Helpmakaar with G Company. The two Lieutenants attempted to escape by crossing the Buffalo River where the Colour fell and was lost downstream, later being recovered. Both officers were killed. At this time the Victoria Cross (VC) was not awarded posthumously. This changed in the early 1900s when both Lieutenants were awarded posthumous Victoria Crosses for their bravery. The 2nd Battalion lost both its Colours at Isandhlwana though parts of the Colours—the crown, the pike and a colour case—were retrieved and trooped when the battalion was presented with new Colours in 1880.

The 24th had performed with distinction during the battle. The last survivors made their way to the foot of a mountain where they fought until they expended all their ammunition and were killed. The 24th Foot suffered 540 dead, including the 1st Battalion's commanding officer.

After the battle, some 4,000 to 5,000 Zulus headed for Rorke's Drift, a small missionary post garrisoned by a company of the 2/24th Foot, native levies and others under the command of Lieutenant Chard, Royal Engineers, the most senior officer of the 24th present being Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead. Two Boer cavalry officers, Lieutenants Adendorff and Vane, arrived to inform the garrison of the defeat at Isandhlwana. The Acting Assistant Commissary James Langley Dalton persuaded Bromhead and Chard to stay and the small garrison frantically prepared rudimentary fortifications.

The Zulus first attacked at 4:30 pm. Throughout the day the garrison was attacked from all sides, including rifle fire from the heights above the garrison, and bitter hand-to-hand fighting often ensued. At one point the Zulus entered the hospital, which was stoutly defended by the wounded inside until it was set alight and eventually burnt down. The battle raged on into the early hours of 23 January but by dawn the Zulu Army had withdrawn. Lord Chelmsford and a column of British troops arrived soon afterwards. The garrison had suffered 15 killed during the battle (two died later) and 11 defenders were awarded the Victoria Cross for their distinguished defense of the post, 7 going to soldiers of the 24th Foot.

54cm long inc haft read more

An Original WW1 M17 Imperial German Stick Grenade Stielhandgranate {aka The Potato Masher}. A Training Smoke Version For Distributing Smoke or Gas To Cover Assaults, Attacks or Retreats By German Shock Troops In The Trenches

Overall in sound condition for age with surface russetting and its end cap is present {often lost}. Heavy rolled steel head, with gas perforations and belt hook and good wooden haft. Original alloy end cap. Übung Stielhandgranate. One side of the stick is marked 5 1/2 Sekunde, indicating that the fuse is a 5 1/2 Second delay. When in training it would contain a small detonation charge

Germany entered World War I with a single grenade type: a heavy 750-gram (26 oz) ball-shaped fragmentation grenade (Kugelhandgranate) for use only by pioneers in attacking fortifications. It was too heavy for regular battlefield use by untrained troops and not suitable for mass production. This left Germany without a standard-issue grenade and improvised designs similar to those of the British were used until a proper grenade could be supplied.

Germany introduced the "stick grenade" in 1915, the second year of the conflict. Aside from its unusual appearance, the Stielhandgranate used a friction igniter system. This had been used in other German grenades, but was uncommon internationally.

During World War I, the Stielhandgranate, under the name M1915 (Model 1915), competed technologically with the British standard-issue Mills bomb series. The first Mills bomb – the grenade No. 5 Mk. 1 – was introduced the same year as the German Model 1915, but due to manufacturing delays it was not widely distributed into general service until 1916. Thus, there was a small period of time where German troops had large supplies of new Model 1915 grenades, while their British opponents only had a small number.

As World War I progressed, the Model 1915 Stielhandgranate was improved with various changes. These variants received designations such as the Model 1916 and the Model 1917.

Otto Dix's Stormtroops Advancing Under a Gas Attack, from his 1924 set of first world war drawings, Der Kreig.

Inert and fully safe. Not suitable for export. read more

375.00 GBP

One Million Viewers!! Google Just Informed Us 1,000,000 People Searched To Find Our Location on Google Maps Since We Updated Our Company Entry Recently.

Google just let us know our updated Google entry just past the amazing 1,000,000 { one million } searches in order to find out our location in order to visit us here in Brighton, England.

Twenty Three Years Ago, After 80 Years Trading in Brighton, We Were Honoured by Being Nominated & Awarded by BACA, In The Best Antique & Collectables Shop In Britain Awards 2001

Presented by MILLER'S Antiques Guide, THE BBC, HOMES & ANTIQUES MAGAZINE, for the British Antique & Collectables Awards. The version of the antique dealers ‘Oscars’ of Britain.

It was a great honour for Mark and David, especially considering at the beginning of the new millennium, in the year 2000, there was over 7,000 established antique and collectors shops in the UK, according to the official Guide to the Antique Shops of Britain, 1999-2000, and we were nominated, and voted into in the top four in Britain.

We were also very kindly described and listed as one of the most highly recommended visitors attractions in the whole of Europe and the UK by nothing less than the 'New York Times ' within their travel guide "New York Times, 36 Hours, 125 Weekends in Europe read more

Price

on

Request

A 18th to Mid 19th Century Steel, Indo Persian, Double Crescent Blade Headed War Axe and Spike, Known as a Tabarzin

Of a type carried into battle by Indo-Persian/Mughal warriors. With engraved bird and floral decoration to the axe heads. Iron shaft.

The double head war axe with spike would have been a very effective battlefield weapon and had excellent balance.

The term tabar is used for axes originating from the Ottoman Empire, Persia, Armenia, India and surrounding countries and cultures. As a loanword taken through Iranian Scythian, the word tabar is also used in most Slavic languages as the word for axe.

The tabarzin (saddle axe) (Persian: تبرزین; sometimes translated "saddle-hatchet") is the traditional battle axe of Persia. It bears one or two crescent-shaped blades. The long form of the tabar was about seven feet long, while a shorter version was about three feet long or less. What makes the Persian axe unique is the very thin handle, which is very light and always metallic. The tabarzin was sometimes carried as a symbolic weapon by wandering dervishes (Muslim ascetic worshippers). The word tabar for axe was directly borrowed into Armenian as tapar (Armenian: տապար) from Middle Persian tabar, as well as into Proto-Slavonic as "topor" (*toporъ), the latter word known to be taken through Scythian, and is still the common Slavic word for axe.

A delightful example of a ceremonial axe in war axe form read more

495.00 GBP

Another Fabulous Christmas Gift Idea. A Superb Pair of Regency Silhouette Portraits of a Scottish Lady and Gentleman, Possibly by George Atkins

Circa 1815 to 1830 British School. The gentleman is holding his fouling piece, and wearing a kilt. The lady is holding what appears to be her prayer book. Both silhouettes are hand cut black paper aplied to an off-white card backing, emphasized with gold shadow highlights. Original Regency rosewood frames. A silhouette is the image of a person, animal, object or scene represented as a solid shape of a single colour, usually black, with its edges matching the outline of the subject. The interior of a silhouette is featureless, and the silhouette is usually presented on a light background, usually white, or none at all. The more expensive versions could have a gold highlight such as these have. The silhouette differs from an outline, which depicts the edge of an object in a linear form, while a silhouette appears as a solid shape. Silhouette images may be created in any visual artistic media, but were first used to describe pieces of cut paper, which were then stuck to a backing in a contrasting colour, and often framed.

Cutting portraits, generally in profile, from black card became popular in the mid-18th century, though the term silhouette was seldom used until the early decades of the 19th century, and the tradition has continued under this name into the 21st century. They represented an effective alternative to the portrait miniature, and skilled specialist artists could cut a high-quality bust portrait, by far the most common style, in a matter of minutes, working purely by eye. Other artists, especially from about 1790, drew an outline on paper, then painted it in, which could be equally quick.

From its original graphic meaning, the term silhouette has been extended to describe the sight or representation of a person, object or scene that is backlit, and appears dark against a lighter background. Anything that appears this way, for example, a figure standing backlit in a doorway, may be described as "in silhouette". Because a silhouette emphasises the outline, the word has also been used in the fields of fashion and fitness to describe the shape of a person's body or the shape created by wearing clothing of a particular style or period. 10.5 x 12.5 inches framed. Picture in the gallery of a drawing a Silhouette by Johann Rudolph Schellenberg (1740?1806). Light staining to the gentlemans white backing paper. read more

595.00 GBP

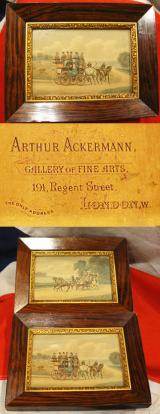

What a Superb Antique Christmas Gift Idea. A Pair of Simply Delightful Original Victorian Royal Mail Coaching Prints in Fine Rosewood Veneer Frames

With their original and super old retailer's labels of the most distinguished Arthur Ackerman Gallery of Fine Arts, 191 Regent St. London, W. A charming pair of original Victorian coloured prints in fine quality frames. 6.75 inches x 8.75 inches framed In the 18th century travel was hazardous to all. Highwaymen stalked the roads and those leading into London were said to be ‘infested’ with robbers. Romantic tales of masked, gallant gentleman were far from the truth: highwaymen were ruthless and deadly.

On 4 December 1775, a Norwich stagecoach was attacked by a gang of seven highwaymen. The guard shot three robbers before being killed and the coach robbed. Richard ‘Dick’ Turpin, a famous highwayman of the time, was known to torture his victims and would even kill one of his companions to aid his own escape.

‘… recommending the Guarding of all the Horse Mails, as a measure of national importance to which the Public in some degree conceived themselves entitled…’

Francis Freeling, Resident Surveyor, 14th March 1796

A plan was written to guard all horse mails, which included the arming of all guards. In doing so the Post Office would not only secure the vast property conveyed by horse, but also save the expenses incurred in prosecuting a robber. Furthermore, it would maintain regularity of service and eliminate what was seen as a disgrace to both the Office and to the nation.

Surveyors observed that the revenue lost to robbery was twice the sum it would cost to guard the mail: it was the obvious choice. In 1784, John Palmer introduced the first mail coach from Bristol to London. This faster and well-armed postal service proved to be a great deterrent to robbers, as they risked being shot or, if caught, tried and hanged. The first recorded robbery of a mail coach did not occur until 25 July 1786.

A letter to joint Postmaster Generals asking for the establishment of a regional mail coach was signed by over 100 people, whose businesses had been damaged due to the frequency of robberies. Mail coaches were a better way of securing the post’s safe passage, though there are a few recorded instances of attempted robberies even of them.

In January 1816, an Enniskillen coach was attacked and robbed by a gang of 14 men who had barricaded the road. The guards fired off all of their ammunition but the mail bags and weapons were all stolen. the Mail Guard was issued with a a pair of flintlock pistols read more

375.00 GBP

A Very Good WW2 1942 German Infantry Fur Backed Tornistor Back-Pack

In very good condition overall, maker stamped and dated 1942 by Lunschloss. This cowhide-covered rucksack was known as the Tornister 34 (developed in 1934) and was later fitted with new style straps in 1939. As the war progressed the design was simplified for economical and practical reasons so the cowhide cover was eliminated making these packs especially scarce on today's collector market.

The M39 has one vertical loop with quick release sewn at the bottom of the front flap for retaining the A-frame and comes with or without carrying straps. Troops that were isssued infantry Y-straps received the version without carrying straps (replaced by two hooks), while troops with no Y-straps received the version with carrying straps.

All of them were produced with a fur front flap (and some without fur) and it was called "Affe" in the German Army read more

295.00 GBP

A Fine Edo Period 17th Cent. Samurai Armour Gosuko, Dangae dou Part Suit of Armour. Shown With A Kabuto For Display Only, {Kabuto Now Sold}

17th century body armour {kabuto helmet sold seperately} comprising full a cuirass {do}, of front and back plates, constructed of iron plates over lacquered and fully laced, and linked with chain mail.

Dangae dou (dō) meaning "step-changing" is a Japanese (samurai) chest armor that is a combination of two or more other styles. The main part of the dou (dō) may be an okegawa dou (dō), but the bottom two lames are laced (kebiki or sugake) instead of riveted or vice versa, or an armour is laced in sugake but the tateage and bottom lames are in kebiki.

Plus, steel chain mail and armour plate arm defences, inner lined with blue green material. The kabuto we show in photos 4 and 5, would compliment it beautifully, and for sale separately {code number 24030}.

During the Heian period (794-1185), the Japanese cuirass evolved into the more familiar style of armour worn by the samurai known as the dou or do. Japanese armour makers started to use leather (nerigawa) and lacquer was used to weather proof the armor parts. By the end of the Heian period the Japanese cuirass had arrived at the shape recognized as being distinctly samurai. Leather and or iron scales were used to construct samurai armours, with leather and eventually silk lace used to connect the individual scales (kozane) which these cuirasses were now being made from.

In the 16th century Japan began trading with Europe during what would become known as the Nanban trade. Samurai acquired European armour including the cuirass and comb morion which they modified and combined with domestic armour as it provided better protection from the newly introduced matchlock muskets known as Tanegashima. The introduction of the tanegashima by the Portuguese in 1543 changed the nature of warfare in Japan causing the Japanese armour makers to change the design of their armours from the centuries-old lamellar armours to plate armour constructed from iron and steel plates which was called tosei gusoku (new armours). Bullet resistant armours were developed called tameshi gusoku or (bullet tested) allowing samurai to continue wearing their armour despite the use of firearms. Please note the helmet is not with the armour. The silk lacing on the breast and back plate is 400 years old and very frayed throughout.

In Japan the term samurai evolved over several centuries

In Japanese, they are usually referred to as bushi (武士,) or buke (武家). According to translator William Scott Wilson: "In Chinese, the character 侍 was originally a verb meaning 'to wait upon', 'accompany persons' in the upper ranks of society, and this is also true of the original term in Japanese, saburau. In both countries the terms were nominalized to mean 'those who serve in close attendance to the nobility', the Japanese term saburai being the nominal form of the verb." According to Wilson, an early reference to the word samurai appears in the Kokin Wakashū (905–914), the first imperial anthology of poems, completed in the first part of the 10th century.

Originally, the word samurai referred to anyone who served the emperor, the imperial family, or the imperial court nobility, even in a non-military capacity.It was not until the 17th century that the term gradually became a title for military servants of warrior families, so that, according to Michael Wert, "a warrior of elite stature in pre-seventeenth-century Japan would have been insulted to be called a 'samurai'".

In modern usage, bushi is often used as a synonym for samurai read more

2850.00 GBP