A Fine Shinto Period Handachi Mounted Armour & Kabuto Cleaving Katana Signed Nobutsugu, With a Fabulous Notare Hamon, Handachi Mounted with Tsuba Of Watanabe no Tsuna and The Rashomon Demon, Ibaraki-Dōji, At The Gate of the Modoribashi Bridge

The blade is signed Nobutsugu, that is likely Higo kuni Dotanuki Nobutsugu, circa 1590, a master smith famed for his swords of great heft and incredibly robust, which this sword, most unusually, clearly demonstrates in abundance. The blades gunome notare hamon is simply fabulous, and the blade is in stunning condition.

The original Edo period urushi lcquer is stunning, designed and a combination of black over dark red that is, with incredibly subtlety, relief surface carved with mokume (木目) which is a Japanese term meaning "wood grain" or "wood eye," and over decorated with Katchimushi {dragonflies}. Truly wonderous skill is demonstrated in this fabulous design, that is almost invisible to the unobservant eye. A masterpiece of the urushi lacquer art.

The saya is also wrapped in its old and fine original silk sageo cord.

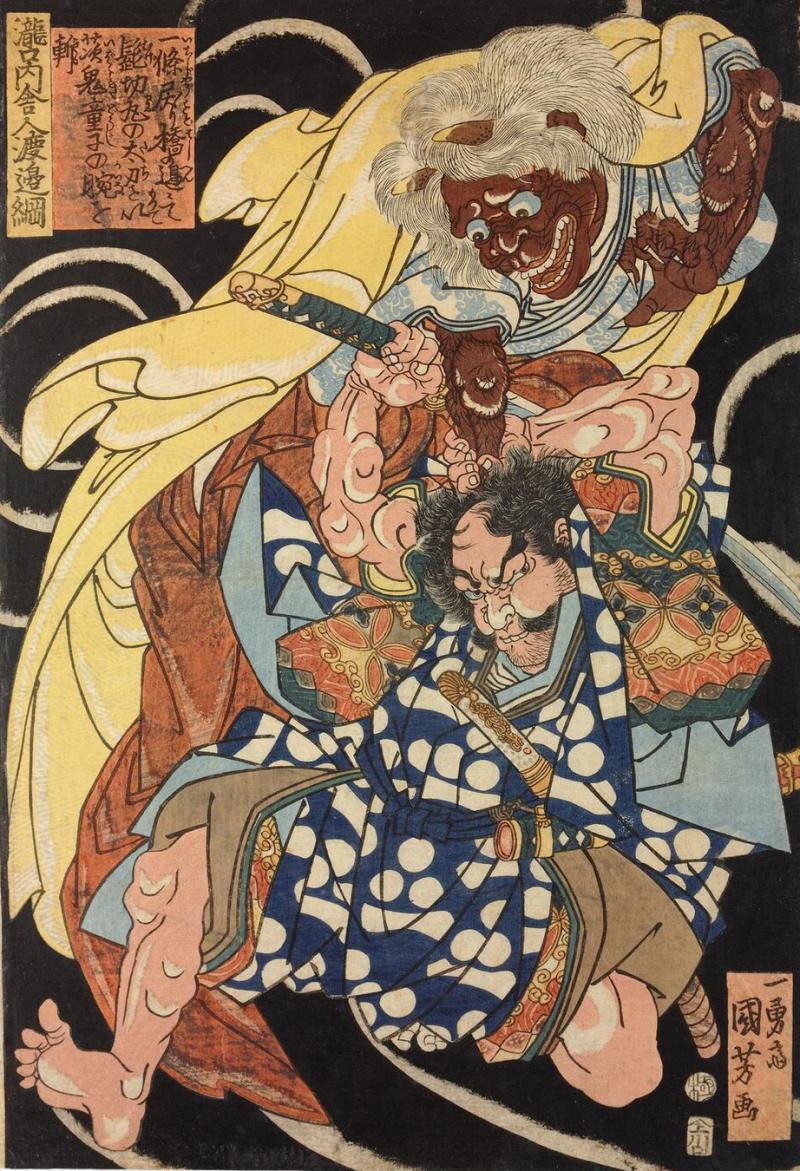

The sukashi tsuba is made in patinated copper, the type of shape known as maru gata, and with the design of the legend of ‘Watanabe no Tsuna and the Rashomon demon’ that tells of the 10th-century warrior who fought and severed the arm of an oni (demon), named Ibaraki, at Kyoto's ruined Rashomon Gate, the Modoribashi Bridge. A story most popular in Japanese folklore, art (like ukiyo-e prints), and theatre, that is culminating in the demon tricking Tsuna into returning the arm by disguising itself as his aunt.

The blade is extraordinary, that although it is not long, it is immensely powerful, and possesses the thickness, strength and heft, of both an armour & helmet piercing sword, in fact, as soon as one handles this sword for the first time, it is immediately obvious as to the character of the power of this blade. Specifically designed as it was, for an incredibly strong cut, that could cleave a samurai, within his armour and kabuto helmet, clean in two. Or, even possibly, as it bears the tsuba of Watanabe no Tsuna, the samurai that legendarily severed an arm off the demon of the Rashomon gate, it is its sword mount that is meant to symbolise the very essence of this sword, as one so powerful, it could even cut through the arm of an Oni demon.

It is mounted in a full suite of fine, hand engraved, handachi mounts, upon both the tsuka and saya, of sinchu, hand engraved with florid scrolls, and sinchu menuki surface decorated with gilded takebori flowers, and with fine, golden brown tsukaito, bound over traditional samegawa {giant rayskin}

The blade has a fabulous, deep and profound, notare hamon, that is wonderfully defined.

Han-dachi mounted swords originally appeared during the Muromachi period when there was a transition taking place from tachi mounting to katana. The sword was being worn more and more edge up, when on foot, but edge down on horseback, as it had always been. The handachi is a response to the need for a sword to be worn in either style.

The samurai were roughly the equivalent of feudal knights. Employed by the shogun or their daimyo lords, they were members of hereditary warrior class that followed a strict "code" that defined their clothes, armour and behaviour on the battlefield. But unlike most medieval knights, samurai warriors could not only read, they were well versed in Japanese art, literature and poetry.

The story that is told by the tsuba;

One stormy night, Watanabe no Tsuna, a samurai retainer of Minamoto no Yorimitsu, was waiting at the dilapidated Rashomon Gate. A demon, Ibaraki-doji, was revealed and attacked him, tugging at his helmet. However,

Tsuna, a most capable and valiant warrior, drew his sword and sliced off the demon's arm in a fierce struggle.

The demon fled, leaving its arm behind, which Tsuna took as a trophy and locked within a chest.

A few days later, an old woman, claiming to be Tsuna's aunt (Mashiba), visited him. She asked to see the severed arm, and when Tsuna opened the chest, she revealed herself as Ibaraki himself in disguise, grabbed his arm, and escaped.

The story of Watanabe no Tsuna (the hero) and Ibaraki-doji (the demon), combatting at the decaying Rashomon Gate in Kyoto, a place associated with ghosts and demons.

It represents themes of bravery, cunning, supernatural encounters, and the deceptive nature of appearances.

This legend became a famous motif in Japanese art, particularly in woodblock prints (ukiyo-e) by artists like Chikanobu and Yoshitoshi, depicting the dramatic fight and the demon's escape.

It's a classic tale featured in Noh, Kabuki, and other popular narratives.

The symbolism of the Katchimushi {dragonfly} decor of the saya;

Japan was once known as the “Land of the Dragonfly”, as the Emperor Jimmu is said to have once climbed a mountain in Nara, and looking out over the land, claimed that his country was shaped like two Akitsu, the ancient name for the winged insects, mating.

Dragonflies appeared in great numbers in 1274 and again in 1281, when Kublai Khan sent his Mongol forces to conquer Japan. Both times the samurai repelled the attackers, with the aid of huge typhoons, later titled Kamikaze (the Divine Winds), that welled up, destroying the Mongol ships, saving Japan from invasion. For that reason, dragonflies were seen as bringers of divine victory.

Dragonflies never retreat, they will stop, but will always advance, which was seen as an ideal of the samurai. Further, although the modern Japanese word for dragonfly is Tombo, the old (Pre Meiji era) word for dragonfly was Katchimushi. “Katchi” means “To win”, hence dragonflies were seen as auspicious by the samurai.

The condition of all parts is excellent with just a few, very small, but usual combat bruises, to the old and original, Edo period lacquer surface to the swords saya.

Overall the sword is 38 inches long, and the blade 26 inches long, habaki to tip.

Code: 26015

6950.00 GBP