An Original Congolese Songye Fetish Female 'Power Figure'. A Most Beautiful and Perfect Example Of The Combination of Esoteric, Spiritually Symbolic & Cultural African Tribal Art From The Last Century. Late 19th to Early 20th Century.

Songye fetish figures were used as an effective instrument for healing, fertility and protection from evil spirits, sorcerers and hostile powers. The figure is in good condition. The face has sensitively rendered features, with semi-circular eyes that are closed they anlmost extend on either side towards the jaw lines. These give the face its distinctive V-shape, interrupted by the short horizontal line of the chin The chest binding is in hide leather, with hands to the abdomen, and a hide skin waist skirt, The figure’s feet and circular base, carved from the same piece of wood as the rest of the figure, and overall it has a rich reddish brown patina.

Nkisi, in west-central African lore, any object or material substance invested with sacred energy and made available for spiritual protection. One tradition of the Kongo people of west-central Africa holds that the god Funza gave the world the first nkisi. Africans uprooted during the Atlantic slave-trade era carried with them some knowledge of nkisi making. In places throughout the United States, particularly in the Deep South, African descendants still create minkisi. Nkisi making is also found throughout the Caribbean and South America, in places such as Cuba, Haiti, and Brazil.

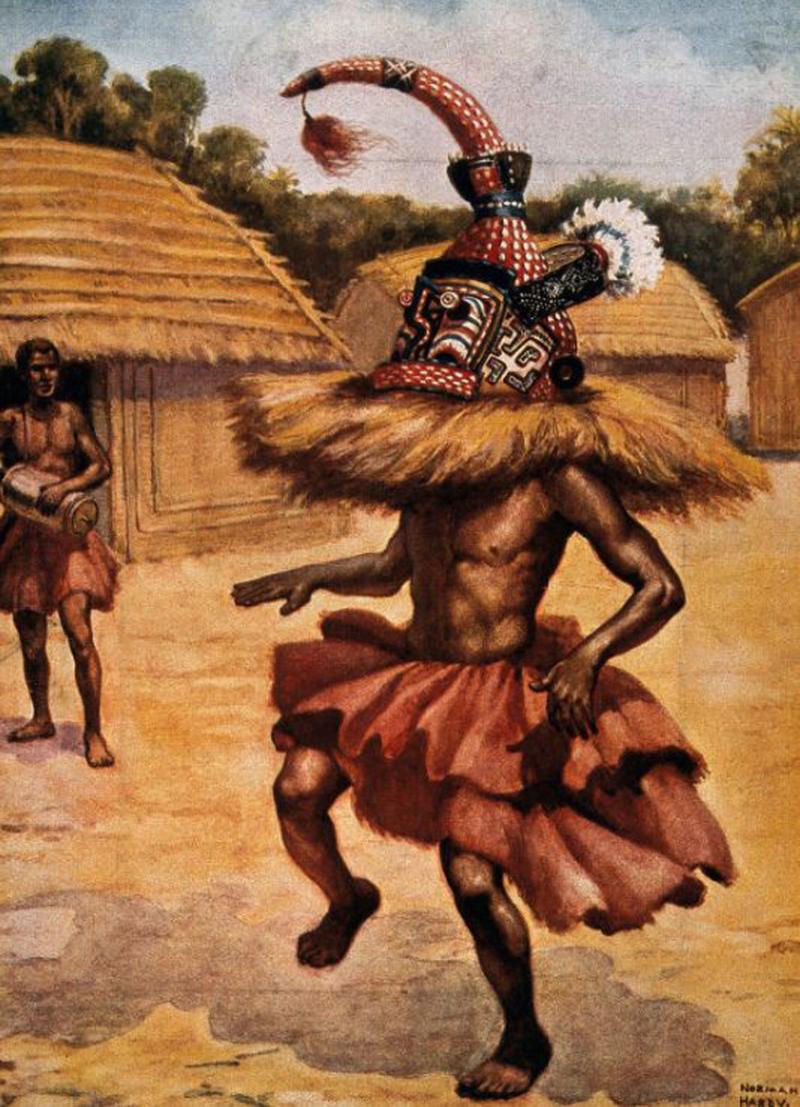

This wild appearance of the Nganga was intended to create a frightening effect, or kimbulua in the Kongo language. The nganga's costume was often modeled on his nkisi. The act of putting on the costume was itself part of the performance; all participants were marked with red and white stripes, called makila, for protection.

The "circles of white around the eyes" refer to mamoni lines (from the verb mona, to see). These lines purport to indicate the ability to see hidden sources of illness and evil.

Yombe nganga often wore white masks, whose color represented the spirit of a deceased person. White was also associated with justice, order, truth, invulnerability, and insight: all virtues associated with the nganga.

The nganga is instructed in the composition of the nkondi, perhaps in a dream, by a particular spirit. In one description of the banganga's process, the nganga then cuts down a tree for the wood that s/he will use to construct the nkondi. He then kills a chicken, which causes the death of a hunter who has been successful in killing game and whose captive soul subsequently animates the nkondi figure. Based on this process, *Gell writes that the nkondi is a figure an index of cumulative agency, a "visible knot tying together an invisible skein of spatio-temporal relations" of which participants in the ritual are aware

After a tribal carver artist completed carving the artifact, the "nganga" transformed it into an object capable of healing illness, settling disputes, safeguarding the peace, and punishing wrongdoers. Each work of this kind or "nkisi" is associated with a spirit, that is subjected to a degree of human control.

Europeans may have encountered these objects during expeditions to the Congo as early as the 15th century. However, several of these fetish objects, as they were often termed, were confiscated by missionaries in the late 19th century and were destroyed as evidence of sorcery or heathenism. Nevertheless, several were collected as objects of fascination and even as an object of study of Kongo culture. Kongo traditions such as those of the nkisi nkondi have survived over the centuries and migrated to the Americas and the Caribbean via Afro-Atlantic religious practices such as vodun, Palo Monte, and macumba. In Hollywood these figures have morphed into objects of superstition such as New Orleans voodoo dolls covered with stick pins. Nonetheless, minkisi have left an indelible imprint as visually provocative figures of spiritual importance and protection.

Adorned with additional objects, Bajimba, with magical properties (horns, skins, teeth, hair, feathers, beads, tacks, cloth, etc.), they gained their power not from the carver but from the Nganga, or spiritual leader. Their carving was considered secondary to their power. Often too powerful to touch, they were moved with long sticks. Although protective, these are confrontational objects, with a warrior's attitude.

Each power figure has a distinct personality, ranging from contemplative to angry to soulful to reserved to compassionate. The ability to suggest those qualities visually with such immediacy and precision is one of the most impressive aspect of the surviving figures.

Kongo religion Kikongo: Bukongo. Bakongo religion was translocated to the Americas along with its enslaved practitioners. Some surviving traditions include conjure, dreaming, possession by the dead to learn wisdom from the ancestors, traditional healing and working with minkisi. The spiritual traditions and religions that have preserved Kongo traditions include Hoodoo, Palo Monte, Lumbalú, Kumina, Haitian Vodou, Candomblé Bantu, Kongo traditions such as those of the nkisi nkondi have survived over the centuries and migrated to the Americas and the Caribbean via Afro-Atlantic religious practices such as vodun, Palo Monte, and macumba.

Similar examples in the Smithsonian and Metropolitan in the USA. One very similar nkisi, from the late 19th to mid 20th century has been a highlight of the Rockefeller collection since its acquisition in 1952. we show examples of the similar Kongo type as ours, from around the same time, in the gallery of photographs

Photo 7 shows a male example from the The Michel Gaud collection

Sothebys Important African Art: ‘The Michel Gaud collection’, London, 29th November 1993, lot 132

Photo 8 a larger but similar Nkisi male version of the Songye people’s in the Rockefeller Wing in the Met, although not on view at present.

9 inches high.

For a serious student of such stunning pieces a visit to the The Met is a must for those that reside or able to travel to the US.

Further reading

Hersak, Dunja. 1986. Songye. Masks and Figure Sculpture. London: Ethnographica.

Hersak, Dunja. 2010. "Reviewing power, process, and statement: the case of Songye figures". African Arts. 43: 38-51.

Neyt, François. 2009. Songye: The Formidable Statuary of Central Africa. Munich: Prestel.

Petridis, Constantine. 2009. Art and power in the central African Savanna: Luba, Songye, Chokwe, Luluwa. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art

Code: 25680

750.00 GBP