One of The Rarest We Have Ever Seen, An Early Crusades Period 10th Century, Byzantine, Ceramic Greek Fire 'Grenade' Superbly Decorated With Incised Individual Flames & A Moulded 'Ball of Fire' Decor Spout Surround. Around 1,100 Years Old

Of semi ovoid tear-drop form. A rare most collectable ancient artefact and a wonderful conversation piece. Circa 10th century ad. A grey ceramic globular vessel of tear-drop form,. With an incised pattern throughout of individual flames. The filling spout is decorated with a moulded embossed relief flaming ball design {around the combination filling and fuse spout} to symbolise what it is, an incendiary grenade that is effectively a ball of fire. Although such surviving original pieces are most rare, this is the first in fifty years we have had that is decorated by incisions in the ceramic that demonstrate its actual purpose. All our previous examples, that we have found in the past 50 years, are either plain or simply decorated with ribbing or angular incisions.

History of the grenade;

Although grenades rose to prominence as weapons during the 20th century, grenades have much longer history that goes back over 1000 years.

They are first thought to have been used by the Byzantine Empire from around the seventh century AD. Clay vessels were filled with flammable liquid known as Greek fire and flung at the enemy.

They were often piled into catapults to increase the range and devastation they caused.

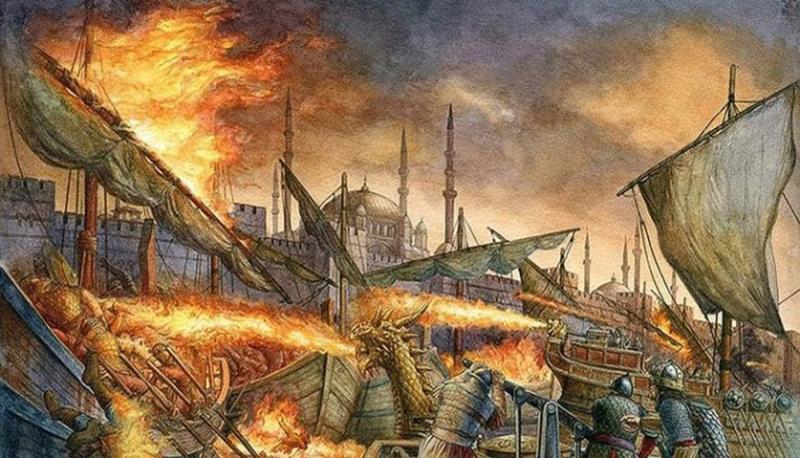

They were popular weapons in naval battles as the fire could easily spread on ships and cause devastation. In its earliest form, Greek fire was hurled onto enemy forces by firing a burning cloth-wrapped ball, perhaps containing a flask, using a form of light catapult, most probably a seaborne variant of the Roman light catapult or onager {a torsion powered catapult}. These were capable of hurling light loads, around 6 to 9 kg (13 to 20 lb), a distance of 350-450 m (380-490 yd). Greek fire, was invented in ca. 672, and is ascribed by the chronicler Theophanes to Kallinikos, an architect from Heliopolis in the former province of Phoenice, by then overrun by the Muslim conquests. The historicity and exact chronology of this account is open to question: Theophanes reports the use of fire-carrying and siphon-equipped ships by the Byzantines a couple of years before the supposed arrival of Kallinikos at Constantinople. If this is not due to chronological confusion of the events of the siege, it may suggest that Kallinikos merely introduced an improved version of an established weapon. The historian James Partington further thinks it likely that Greek fire was not in fact the discovery of any single person, but "invented by chemists in Constantinople who had inherited the discoveries of the Alexandrian chemical school".Indeed, the 11th-century chronicler George Kedrenos records that Kallinikos came from Heliopolis in Egypt, but most scholars reject this as an error. Kedrenos also records the story, considered rather implausible, that Kallinikos' descendants, a family called "Lampros" ("Brilliant"), kept the secret of the fire's manufacture, and continued doing so to his day.

The invention of Greek fire came at a critical moment in the Byzantine Empire's history: weakened by its long wars with Sassanid Persia, the Byzantines had been unable to effectively resist the onslaught of the Muslim conquests. Within a generation, Syria, Palestine and Egypt had fallen to the Arabs, who in ca. 672 set out to conquer the imperial capital of Constantinople. The Greek fire was utilized to great effect against the Muslim fleets, helping to repel the Muslims at the first and second Arab sieges of the city. Records of its use in later naval battles against the Saracens are more sporadic, but it did secure a number of victories, especially in the phase of Byzantine expansion in the late 9th and early 10th centuries. Utilisation of the substance was prominent in Byzantine civil wars, chiefly the revolt of the thematic fleets in 727 and the large-scale rebellion led by Thomas the Slav in 821-823. In both cases, the rebel fleets were defeated by the Constantinopolitan Imperial Fleet through the use of Greek fire .

The Byzantines also used the weapon to devastating effect against the various Rus' raids to the Bosporus, especially those of 941 and 1043, as well as during the Bulgarian war of 970-971, when the fire-carrying Byzantine ships blockaded the Danube.

The importance placed on Greek fire during the Empire's struggle against the Arabs would lead to its discovery being ascribed to divine intervention. The Emperor Constantine Porphyrogennetos (r. 945-959), in his book De Administrando Imperio, admonishes his son and heir, Romanos II (r. 959-963), to never reveal the secrets of its construction, as it was "shown and revealed by an angel to the great and holy first Christian emperor Constantine" and that the angel bound him "not to prepare this fire but for Christians, and only in the imperial city". As a warning, he adds that one official, who was bribed into handing some of it over to the Empire's enemies, was struck down by a "flame from heaven" as he was about to enter a church. As the latter incident demonstrates, the Byzantines could not avoid capture of their precious secret weapon: the Arabs captured at least one fire-ship intact in 827, and the Bulgars captured several siphons and much of the substance itself in 812-814 ad. This, however, was apparently not enough to allow their enemies to copy it . The Arabs for instance employed a variety of incendiary substances similar to the Byzantine weapon, but they were never able to copy the Byzantine method of deployment by siphon, and used catapults and grenades instead. In its earliest form, Greek fire was hurled onto enemy forces by firing a burning cloth-wrapped ball, perhaps containing a flask, using a form of light catapult, most probably a seaborne variant of the Roman light catapult or onager. These were capable of hurling light loads around 6 to 9 kg (13 to 20 lb) a distance of 350-450 m (383-492 yd). Later technological improvements in machining technology enabled the devising of a pump mechanism discharging a stream of burning fluid (flame thrower) at close ranges, devastating wooden ships in naval warfare. Such weapons were also very effective on land when used against besieging forces.

Greek fire continued to be mentioned during the 12th century, and Anna Komnene gives a vivid description of its use in a possibly fictional naval battle against the Pisans in 1099. However, although the use of hastily improvised fire-ships is mentioned during the 1203 siege of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade, no report confirms the use of the actual Greek fire, which had apparently fallen out of use by then, either because its secrets were forgotten, or because the Byzantines had lost access to the areas in the Caucasus and the eastern coast of the Black Sea where the primary ingredients were to be found.

Approx 51/2 inches top to bottom.

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery

Code: 25644

995.00 GBP