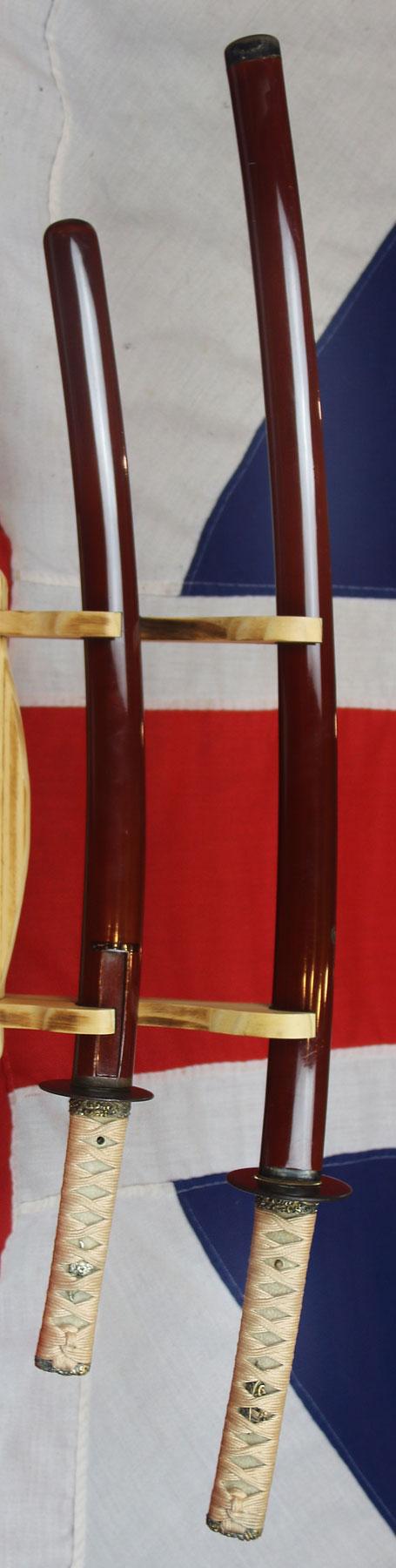

A Beautiful Koto-Shinto Period Signed Yasuhiro, in KiiKuni. Antique Samurai Daisho With Rokakku Clan Mon. Traditional Daisho, the Two Swords Of The Samurai, Comprise a Fine Daito Long Sword & Signed Shoto Short Sword. With With Pierced Rokakko Mon

Signed Koto daisho, circa 16th century , with beautiful elegant blades, the saya are very fine, delicate and rare, light ‘cinnabar red’ lacquer, also known as coromandel red {named from the pink petaled flower} urushi lacquer to the saya, often made with the addition of perilla oil. The condition of both saya is very good just a couple of aged surface nicks

The colour created from urushi lacquer mixed with cinnabar was rewarded to them as the most famous warriors of all the samurai clans of Japan, the Li, and the Takeda.

The blades both have superbly beautiful notare hamon, in very good polish

Signed 記伊國住 康廣

Kii Kuni. Jyu Yasu Hiro.

The meaning is Yasuhiro, who lives in KiiKuni.

However, the first word is written as 記. But the better kanji should be 紀. It is impossible to mistake the name of the place where one lives, so one could research that kanji.

This sword was made in the 1500’s to 1600s. There were two generations of Yasuhiro there at that time.

Their clan mon tettsu tsuba have a polished surface finish bevelled towards the edge. Matching daito long sword and shoto short sword tsubas, very finely pierced with the Rokakku samurai clan's crest, the "kamon". The tsuka ito was rebound in cream silk in the post Taisho period, as is very usual due to the wear and natural aging of the Edo period silk tsuka-ito, and the signed cast fuchi kashira, that have a deep takebori design Hiranami style of crashing waves in gilt over metal, and the four gilt and silvered menuki of samurai are all very likely from that same late period.

Founded by Sasaki Yasutsuna of Omi Province in the 13th century, the name Rokkaku was taken from their residence within Kyoto; however, many members of this family continued to be called Sasaki. Over the course of the Muromachi period, members of the clan held the high post of Constable (shugo) of various provinces.

During the Onin War (1467-77), which marked the beginning of the Sengoku period, the clan's Kannonji Castle came under assault. As a consequence of defeat in the field, the clan entered a period of decline.

Like other hard-pressed daimyos, the Rokakku tried to enhance their military position by giving closer attention to improved civil administration within their domain. For instance, in 1549, the Rokakku eliminated a paper merchant's guild in Mino under penalty of confiscation. Then they declared a free market in its place.

The Rokakku were defeated by Oda Nobunaga in 1568 on his march to Kyoto and in 1570 they were absolutely defeated by Shibata Katsuie. During the Edo period, Rokkaku Yoshisuke's descendants were considered a koke clan. Historically, or in a more general context, the term koke may refer to a family of old lineage and distinction. Tsuba were made by whole dynasties of craftsmen whose only craft was making tsuba. They were usually lavishly decorated. In addition to being collectors items, they were often used as heirlooms, passed from one generation to the next. Japanese families with samurai roots sometimes have their family crest (mon) crafted onto a tsuba. Tsuba can be found in a variety of metals and alloys, including iron, steel, brass, copper and shakudo. In a duel, two participants may lock their katana together at the point of the tsuba and push, trying to gain a better position from which to strike the other down. This is known as tsubazeriai pushing tsuba against each other. A samurai's daisho were his swords, as worn together, as stated in the Tokugawa edicts. In a samurai family the swords were so revered that they were passed down from generation to generation, from father to son. If the hilt or scabbard wore out or broke, new ones would be fashioned for the all-important blade. The hilt, the tsuba (hand guard), and the scabbard themselves were often great art objects, with fittings sometimes of gold or silver. Often, too, they ?told? a story from Japanese myths. Magnificent specimens of Japanese swords can be seen today in the Tokugawa Art Museum?s collection in Nagoya, Japan.

In creating the sword, a sword craftsman, such as, say, the legendary Masamune, had to surmount a virtual technological impossibility. The blade had to be forged so that it would hold a very sharp edge and yet not break in the ferocity of a duel. To achieve these twin objectives, the sword maker was faced with a considerable metallurgical challenge. Steel that is hard enough to take a sharp edge is brittle. Conversely, steel that will not break is considered soft steel and will not take a keen edge. Japanese sword artisans solved that dilemma in an ingenious way. Four metal bars, a soft iron bar to guard against the blade breaking, two hard iron bars to prevent bending and a steel bar to take a sharp cutting edge were all heated at a high temperature, then hammered together into a long, rectangular bar that would become the sword blade. When the swordsmith worked the blade to shape it, the steel took the beginnings of an edge, while the softer metal ensured the blade would not break. This intricate forging process was followed by numerous complex processes culminating in specialist polishing to reveal the blades hamon and to thus create the blade's sharp edge. Inazo Nitobe stated: 'The swordsmith was not a mere artisan but an inspired artist and his workshop a sanctuary. Daily, he commenced his craft with prayer and purification', or, as the phrase was, 'he committed his soul and spirit into the forging and tempering of the steel.'

Celebrated sword masters in the golden age of the samurai, roughly from the 13th to the 17th centuries, were indeed revered to the status they richly deserved.

As once told to us by an esteemed regular visitor to us here in our gallery, and the same words that are repeated in his book;

“In these textures lies an extraordinary and unique feature of the sword - the steel itself possesses an intrinsic beauty. The Japanese sword has been appreciated as an art object since its perfection some time during the tenth century AD. Fine swords have been more highly prized than lands or riches, those of superior quality being handed down from generation to generation. In fact, many well-documented swords, whose blades are signed by their makers, survive from nearly a thousand years ago. Recognizable features of the blades of hundreds of schools of sword-making have been punctiliously recorded, and the study of the sword is a guide to the flow of Japanese history.”

Victor Harris

Curator, Assistant Keeper and then Keeper (1998-2003) of the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum. He studied from 1968-71 under Sato Kenzan, Tokyo National Museum and Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords

Every single item from The Lanes Armoury is accompanied by our unique Certificate of Authenticity. Part of our continued dedication to maintain the standards forged by us over the past 100 years of our family’s trading, as Britain’s oldest established, and favourite, armoury and gallery

Code: 25536

15500.00 GBP