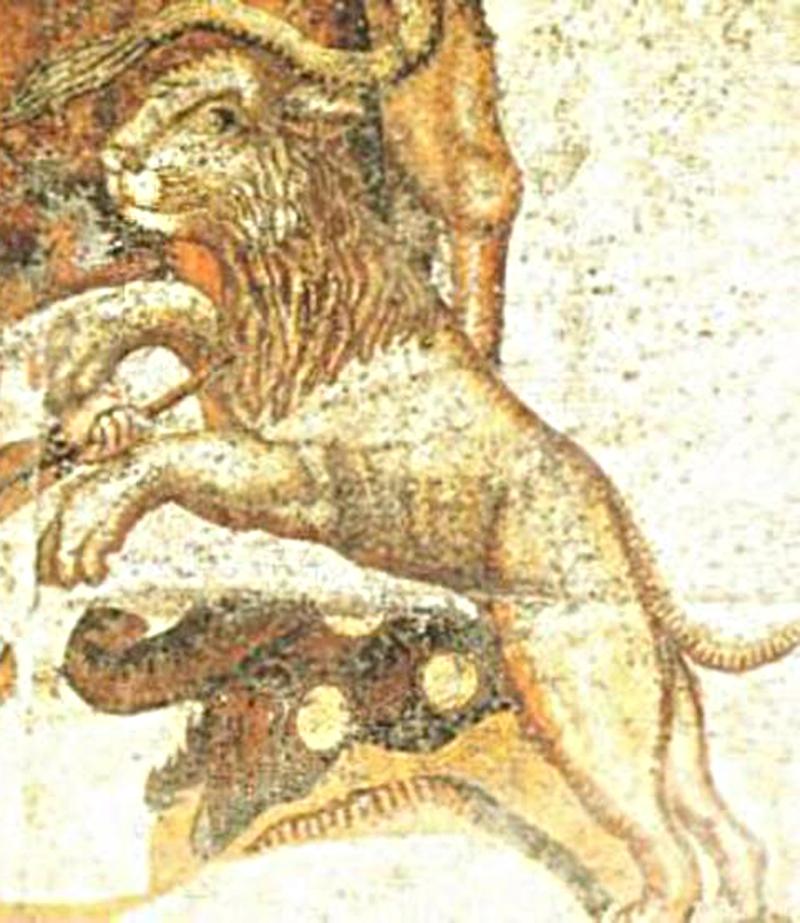

A Rare Original Roman Gladiatrix, {A Female Gladiator} Size Bronze Ring, Early Imperial Roman Period. Featuring A Coliseum Barbary Lion in a Combat Pose Around 1900 Years Old

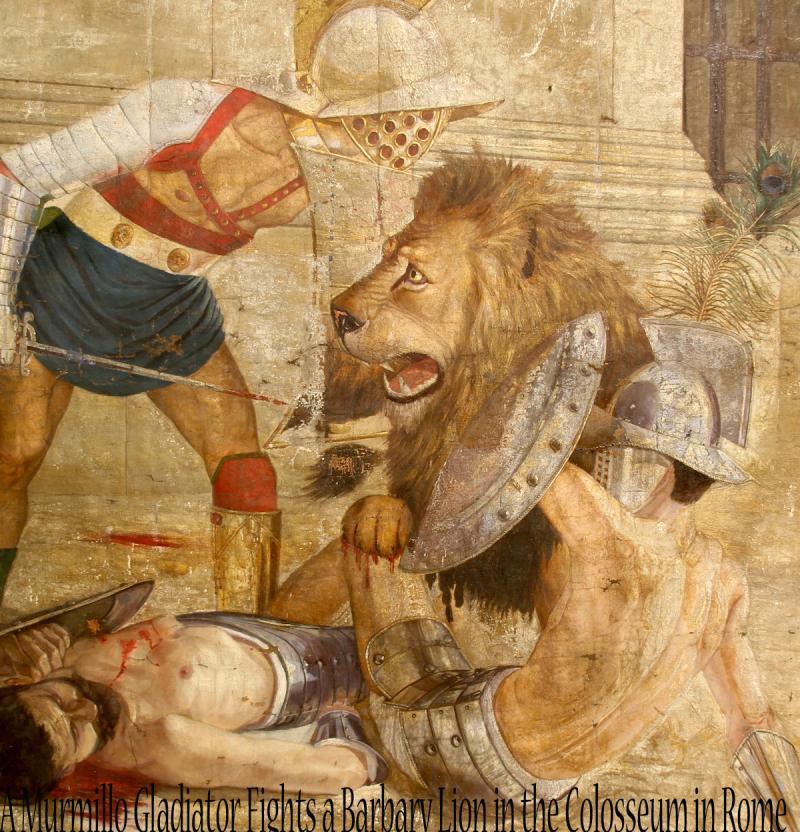

An amazing original historical ancient Roman artefact featuring a detailed intaglio hand engraving of a lion, in a gladiatorial standing pose, with its large mane and proud tail, from such as the gladiator and gladiatrix's arena in the Colosseum in Rome, from the time just before the Emperor's Marcus Aurelias and Commodus. The era superbly depicted in Sir Ridley Scott's blockbuster movie, Gladiator, starring Russell Crowe, and soon to be released Gladiator II.

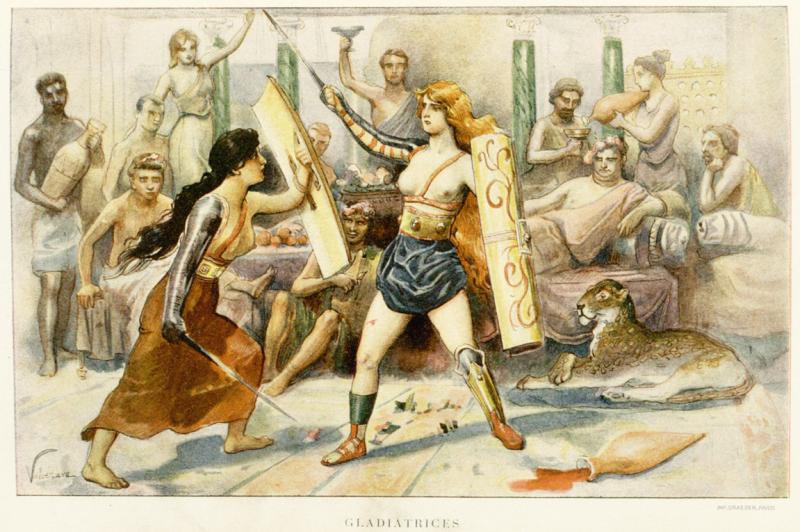

The gladiatrix was a female gladiator of ancient Rome. Like their male counterparts, gladiatrices fought each other, or wild animals, to entertain audiences at games and festivals

Very little is known about female gladiators. They seem to have used much the same equipment as men, but were few in number and almost certainly considered an exotic rarity by their audiences. They are mentioned in literary sources from the end of the Roman Republic and early Roman Empire, and are attested in only a few inscriptions. Female gladiators were officially banned as unseemly from 200 AD onwards, but the word gladiatrix does not appear until late antiquity.

Tacitus writes of women of high status flaunting themselves in the arena during the time of Nero (Annals 15.32). Cassius Dio tells of the Emperor Titus putting on a combat where women were pitted against foes (Historia Romana, 67.8.4).

Petronius mentions a troupe of professional gladiators which included a woman fighting on a chariot (Satyricon 45). According to the gossipy Suetonius, the Emperor Domitian sponsored torch-lit combats at night between men and also between women (Domitian 4). Many Roman oil lamps feature gladiators, a handful of which show what seem to be female gladiators.

In copper bronze with stunning, natural age patination, in a regular female size of the time. By far the greatest percentage of rings from the Roman era were engraved in the stylised form, but a very small percent, perhaps less that .01 of a percent, were engraved in the realism form. This is one of those rare types of more realistic engravings.

The wearing of the ring was the prerogative alone of Roman citizens or those of high rank and esteem, that some gladiators always aspired to but rarely achieved due to their short life span within their violent craft. However some did achieve such great success and were rewarded with riches, freedom and the right to wear the traditional Roman bronze status ring.

Romans seem to have found the idea of a female gladiator novel and entertaining, or downright absurd; Juvenal titillates his readers with a woman named "Mevia", a beast-hunter, hunting boars in the arena "with spear in hand and breasts exposed", and Petronius mocks the pretensions of a rich, low-class citizen, whose munus includes a woman fighting from a cart or chariot.

Some regarded female gladiators of any class as a symptom of corrupted Roman sensibilities, morals and womanhood. Before he became emperor, Septimius Severus may have attended the Antiochene Olympic Games, which had been revived by the emperor Commodus and included traditional Greek female athletics. Septimius' attempt to give Romans a similarly dignified display of female athletics was met by the crowd with ribald chants and cat-calls.26 Probably as a result, he banned the use of female gladiators, from 200 AD.27

There may have been more, and earlier female gladiators than the sparse evidence allows; *McCullough speculates the unremarked introduction of lower-class gladiatores mulieres at some time during the Augustan era, when the gift of luxurious, crowd-pleasing games and abundant novelty became an exclusive privilege of the state, provided by the emperor or his officials. On the whole, Rome's elite authorities exhibit indifference to the existence and activities of non-citizen arenari of either gender. The Larinum decree made no mention of lower-class mulieres, so their use as gladiators was permissible. Septimius Severus' later wholesale ban on female gladiators may have been selective in its practical application, targeting higher-status women with personal and family reputations to lose. Nevertheless, this does not imply low-class female gladiators were commonplace in Roman life. Male gladiators were wildly popular, and were celebrated in art, and in countless images across the Empire. Only one near-certain image of female gladiators survives; their appearance in Roman histories is extremely rare, and is invariably described by observers as unusual, exotic, aberrant or bizarre.

The following historical quote from Antiquity is from Cassio Dios book of Roman History and is translated by Earnest Cary and Herbert Baldwin Foster. The succeeding quote is from Juvenals book Satire; which is translated by Niall Rudd.

“There was another exhibition that was once most disgraceful and most shocking, when men and women not only of the equestrian but even of the senatorial order appeared as performers in the orchestra, in the Circus, and in the hunting-theatre Colosseum, like those who are held in lowest esteem. Some of them played the flute and danced in pantomimes or acted in tragedies and comedies or sang to the lyre; they drove horses, killed wild beasts and fought as gladiators, some willingly and some sore against their will.”

“What sense of shame can be found in a woman wearing a helmet, who shuns femininity and loves brute force… If an auction is held of your wife’s effects, how proud you will be of her belt and arm-pads and plumes, and her half-length left-leg shin guard! Or, if instead, she prefers a different form of combat, how pleased you’ll be when the girl of your heart sells off her greaves! Hear her grunt while she practices thrusts as shown by the trainer, wiling under the weight of the helmet.”

A gladiator was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their lives and their legal and social standing by appearing in the arena. Most were despised as slaves, schooled under harsh conditions, socially marginalised, and segregated even in death. However, success in the arena could mean riches and fame beyond their wildest dream. For many this was the greatest escape from slavery there was.

Irrespective of their origin, gladiators offered spectators an example of Rome's martial ethics and, in fighting or dying well, they could inspire admiration and popular acclaim. They were celebrated in high and low art, and their value as entertainers was commemorated in precious and commonplace objects throughout the Roman world.

The origin of gladiatorial combat is open to debate. There is evidence of it in funeral rites during the Punic Wars of the 3rd century BC, and thereafter it rapidly became an essential feature of politics and social life in the Roman world. Its popularity led to its use in ever more lavish and costly games.

The gladiator games lasted for nearly a thousand years, reaching their peak between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century AD the time of Emperor Commodus. Christians disapproved of the games because they involved idolatrous pagan rituals, and the popularity of gladiatorial contests declined in the fifth century, leading to their disappearance.

Commodus was the Roman emperor who ruled from 177 to 192. He served jointly with his father Marcus Aurelius from 177 until the latter's death in 180, and thereafter he reigned alone until his assassination. His reign is commonly thought of as marking the end of a golden period of peace in the history of the Roman Empire, known as the Pax Romana.

Commodus became the youngest emperor and consul up to that point, at the age of 16. During his solo reign, the Roman Empire enjoyed reduced military conflict compared with the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Intrigues and conspiracies abounded, leading Commodus to revert to an increasingly dictatorial style of leadership, culminating in his creating a deific personality cult, with his performing as a gladiator in the Colosseum. Throughout his reign, Commodus entrusted the management of affairs to his palace chamberlain and praetorian prefects, named Saoterus, Perennis and Cleander.

Commodus's assassination in 192, by a wrestler in the bath, marked the end of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was succeeded by Pertinax, the first emperor in the tumultuous Year of the Five Emperors.

Most gladiators paid subscriptions to "burial clubs" that ensured their proper burial on death, in segregated cemeteries reserved for their class and profession. A cremation burial unearthed in Southwark, London in 2001 was identified by some sources as that of a possible female gladiator (named the Great Dover Street woman). She was buried outside the main cemetery, along with pottery lamps of Anubis (who like Mercury, would lead her into the afterlife), a lamp with the image of a fallen gladiator, and the burnt remnants of Stone Pine cones, whose fragrant smoke was used to cleanse the arena. Her status as a true gladiatrix is a subject of debate. She may have simply been an enthusiast, or a gladiator's ludia (wife or lover).17 Human female remains found during an archaeological rescue dig at Credenhill in Herefordshire have also been speculated in the popular media as those of a female gladiator

As with all our items it comes complete with our certificate of authenticity

*McCullough, Anna, “Female Gladiators in the Roman Empire”, in: Budin & Turfa (eds), Women in Antiquity: Real Women across the Ancient World, Routledge (2016), p. 958, citing Scholia in Iuvenalem Vetustiora, on Juvenal, Satire 6, 250-251 nam vere vult esse gladiatrix quae meretrix "for she really wants to be a gladiator who is a harlot"

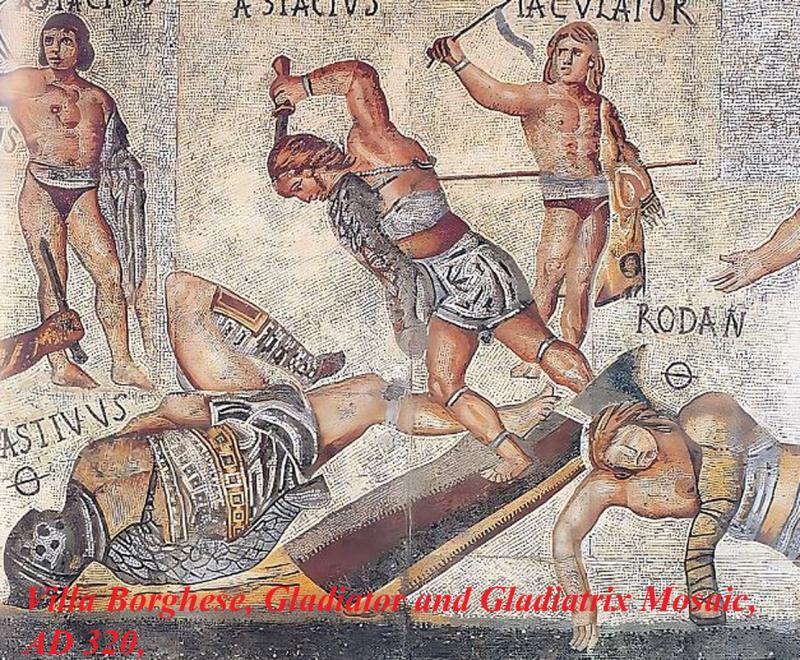

Detail from the Villa Borghese gladiator and gladiatrix mosaic, AD 320, and discovered in 1834 (Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy).

UK {female} size I approx. Slightly ovoid through ancient wear

Code: 25465

795.00 GBP