A Fabulous And Incredibly Rare Museum Piece. An Original WW2 SOE {Special Operations Executive} Secret Espionage Agent's Suitcase Radio Transmitter & Reciever of an Agent of the Secret Army 1942/3 Issue

SOLD

SOE Special forces

Role; Espionage Irregular warfare (especially sabotage and raiding operations) Special reconnaissance

Nickname "The Baker Street Irregulars" "Churchill's Secret Army" "Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare"

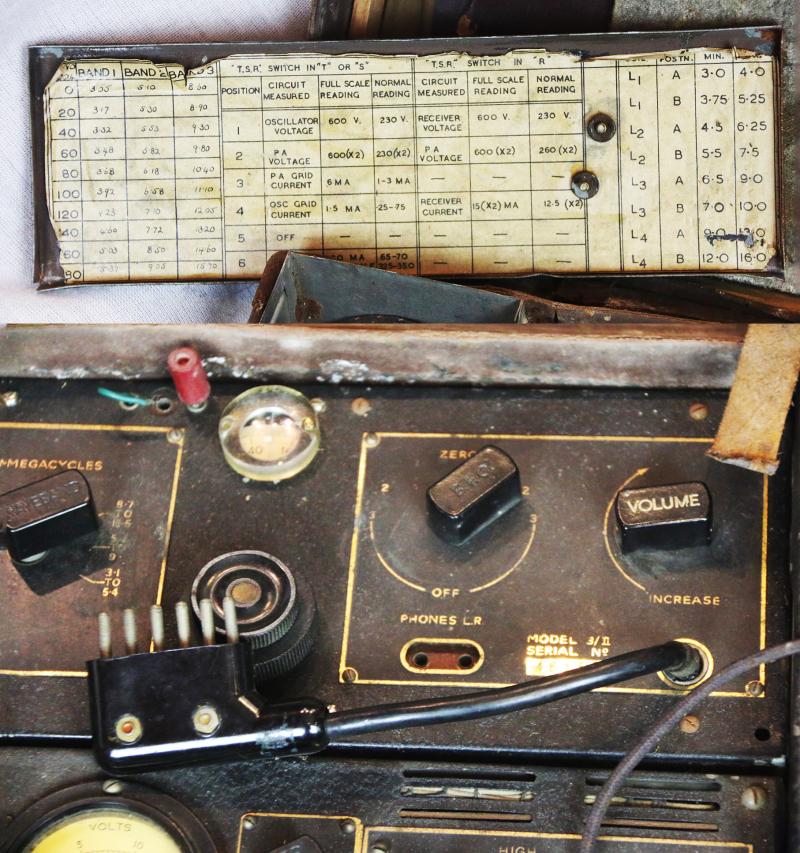

A phenomenally rare, complete mid war WW2 SOE spy radio set, transceiver, with Morse key, earphone headset and various and numerous components, including five crystal units and four frequency ranges, L1B, L2A, L3A and L4A. in it's original case with the early central lock and two catches. {later models changed to just two catches}. Handle detached. Parts with some damage, overall, completely untouched condition since the 1940's. An iconic and most rarest of so-called ‘barn finds’. It may indeed be one of the rarest in the world, and as such an incredible and unique piece of original spy-craft history.

Developer of the transceiver was Captain John Brown (SOE).

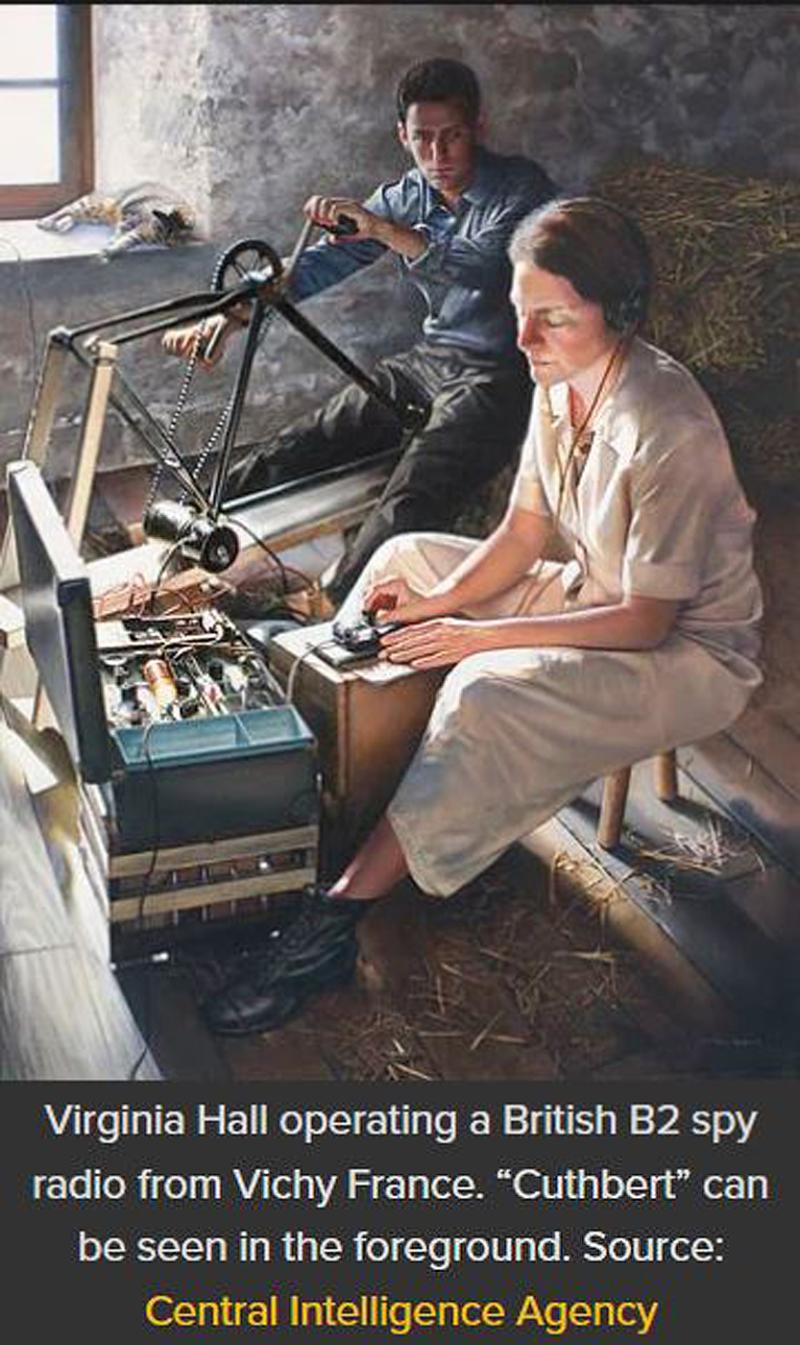

The type used by SOE and OSS agent Virginia Hall. Dubbed by the Gestapo as the Limping Lady, as she had a wooden leg! { that she called Cuthbert}.

She had all the makings of a diplomat. Impeccably educated, fluent in multiple languages, and worldly from her years spent abroad from her native Baltimore, Virginia’s dream of a life in the foreign service was shattered when a hunting accident led to the amputation of her left leg. Attitudes toward disabilities were different in the 1930s, and even fitted with a prosthetic leg (which she named “Cuthbert”) Virginia was deemed unfit for the life of a diplomat.

The outbreak of WWII changed that attitude. Virginia, by then living in France, was well-placed to act as a forward agent for the Allies. Volunteering first for the British Special Operations Executive (SOE), Virginia worked agents, ran safehouses, and reported intelligence from Vichy France. Later, she volunteered with the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS), forerunner to the CIA. Her efforts earned her a place on the Gestapo’s “Most Wanted” list as “The Limping Lady”. She and Cuthbert continued to work against the Nazis right up through the Normandy invasion and liberation and earned a Distinguished Service Cross for her efforts – a rare honour for a civilian, and rarer still for a woman.

This is the first we have ever seen, in 80 years since WW2, to be complete, original, and untouched, outside of the Imperial War Museum or the very few dedicated spy and espionage museums. In the world of the most valuable vintage car collecting, this would be an iconic ‘barn find’ of the very rarest kind. In that most exclusive of worlds ‘barn finds’ are now achieving prices equal to fully restored and now mint equivalent motor cars. Millions of pounds can now change hands for an abandoned rarely seen car newly discovered as a total wreck in, say, a barn, garage or field, that has lain untouched, rotting and unloved for many decades.

After France signed an armistice with Germany in June 1940, Great Britain feared the shadow of Nazism would continue to fall over Europe. Dedicated to keeping the French people fighting, Prime Minister Winston Churchill pledged the United Kingdom’s support to the resistance movement. Charged with “set(ting) Europe ablaze,” the Special Operations Executive, or SOE, was born.

Used by the most dedicated and bravest of people, men and women, who have ever served their country. Agents, such as Violette Szabo and Noor Inayat Khan, code name Madeleine, who only too well knew their chances of surviving without capture, torture and execution were slim at best. For them, and many, many others, survival was not to be.

Headquartered at 64 Baker Street in London, the SOE’s official purpose was to put British special agents on the ground to “coordinate, inspire, control and assist the nationals of the oppressed countries.” Minister of Economic Warfare Hugh Dalton borrowed irregular warfare tactics used by the Irish Republican Army two decades before. The “Baker Street Irregulars,” as they came to be known, were trained in sabotage, small arms, radio and telegraph communication and unarmed combat. SOE agents were also required to be fluent in the language of the nation in which they would be inserted so they could fit into the society seamlessly. If their presence aroused undue suspicion, their missions could well be over before they even began.

Portable communication devices were of utmost importance as radio and telegraph communication ensured the French resistance (and SOE agents) were not cut off from the outside world. Radio operators had to stay mobile, often carrying their radio equipment on their backs as they moved from safe house to safe house. Their survival depended on their ability to transmit messages rapidly and move quickly.

Along with irregular tactics and unusual materiel, the British government knew an irregular war required irregular warriors. Women proved to be invaluable as couriers, spies, saboteurs and radio operators in the field. Though female agents received the same training as the men, some balked at the idea of sending women behind enemy lines. They grudgingly agreed female spies would have distinct advantages over the men on the ground. Women could travel freely because they were not expected to work during the day. Gender stereotypes also helped keep the women above suspicion. After all, who could possibly imagine a woman could be a viable combatant in war?

Women were more than viable, however: they were critical to SOE mission success. Though they would later be honored for their “conspicuous courage,” the female spies of the SOE were successful because they learned to be inconspicuous. They took on secret identities, went on secret missions and were trusted with their nation’s greatest secrets. Thirty-nine of the 470 SOE agents in France were women, with an additional sixteen deployed to other areas.

The Gestapo gave Nancy Grace August Wake the nickname “the white mouse” because of her uncanny ability to evade capture. When she learned one of the resistance groups no longer had a radio for communication, she rode almost 300 kilometers on a bicycle to make radio contact with the SOE headquarters and arrange for an equipment drop. Despite many close calls, Wake survived the war. First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) member Odette Hallowes also cheated death. Embedded with the resistance in Cannes, Hallowes was captured and sent to the Ravensbrück concentration camp. She survived two years in prison, often in solitary confinement, before the camp was liberated by the Allied forces.

Other women were not so fortunate. Noor Inayat Khan, code name Madeleine, was a radio operator in France. After her entire team was ambushed and arrested, she was betrayed to the Gestapo by a French national hoping for a large reward. Khan did not break during interrogation and attempted escape from her captors several times. Sent to Dachau in September 1944, she was executed upon arrival. Violette Szabo, an agent inserted into Limoges, faced a similar fate at Ravensbrück. She was 23 years old.

By Kate Murphy Schaefer {abridged}. Kate Murphy Schaefer holds a MA in History with a Military History concentration for Southern New Hampshire University. She is also the author of a woman’s history blog, www.fragilelikeabomb.com.

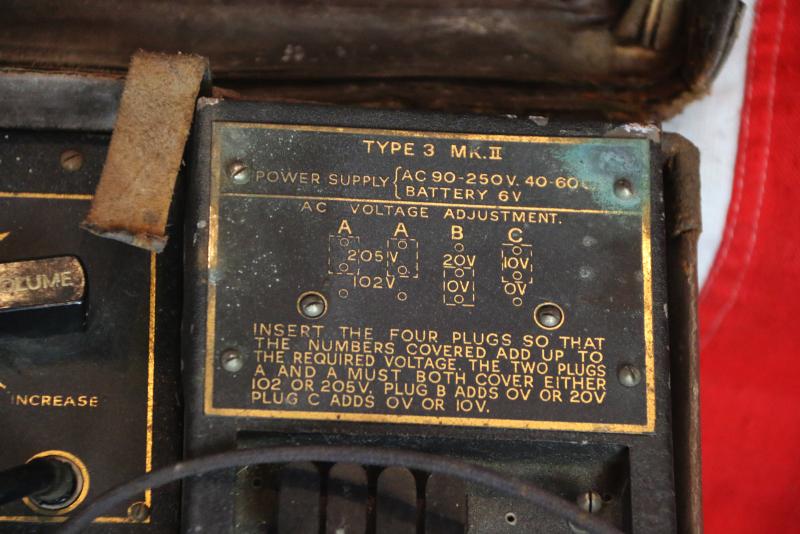

Type 3 Mk. II B2

Clandestine suitcase transceiver · 1942

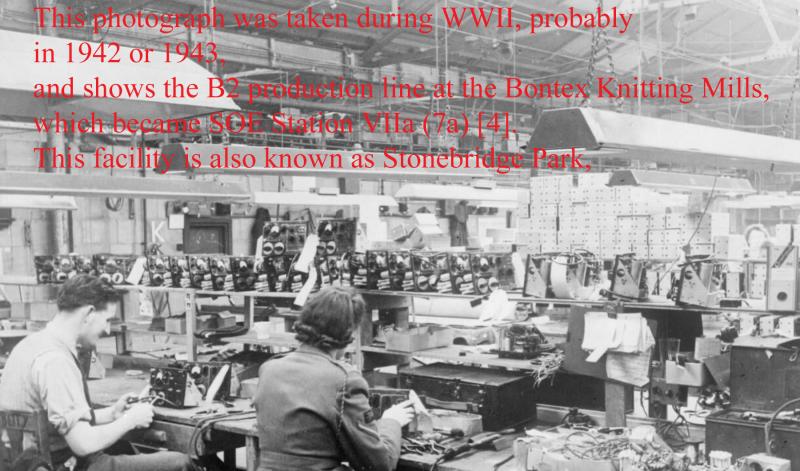

Type 3 Mark II, commonly referred to as B2, is a British WWII portable clandestine transceiver, also known as a spy radio set, developed in 1942 by (then) Captain John Brown at SOE Station IX, and manufactured by the Radio Communication Department of the SOE at Stonebridge Park. The set was issued to agents, resistance groups and special forces, operating on occupied territory. The official designator is Type 3 Mk. II but the radio is also known as Type B Mk. II, B.II and B2.

The B2 came in two versions. The initial version came in an unobtrusive leather suitcase that allowed an agent to travel inconspicuously. This is the most well-known variant. Later in the war it was dropped by parachute in two water-tight containers, that were more suitable for use by resistance groups operating in the field.

The images show the Type 3 Mk.II in its original brown simulated leather suitcase, which can easily be recognized as it has three locks at the front: two simple locks at the sides, and one that can be locked with a key at the centre.

Operating the Type 3 Mark II (B2)

The radio set consists of three units: a receiver (RX), a transmitter (TX) and a Power Supply Unit (PSU), plus a box with spares and accessories. When mounted in the suitcase, the transmitter is located at the center top, with the receiver mounted below it. The PSU is at the right in such a position that the two other units can be connected to it. The spares box is generally positioned at the left, with the Morse key mounted on its lid. When operating the B2, the lid of the spares box should be placed on the table, so that the Morse key can be operated.

The Type 3 Mk.II (B2) was relatively small for its day and produced an HF output power of 20 Watts. Nevertheless, it was too big to carry around unobtrusively especially when travelling by public transport. For this reason, later radios, such as the Model A Mk. III (A3) were made much smaller, albeit with a limited frequency range (3.2-9.55 MHz) and reduced power output (5 Watt).

The most well-known appearance of the B2 is the suitcase version, but hardly any surviving B2 is found in its original red leather suitcase. In fact, the B2 was delivered in a variety of different suitcases, ranging from sturdy leather cases to simple cardboard and even wooden variants.

The original leather case is easily recognised, as it has three locks rather than the usual two. In many cases, the original case was swapped for a more common two-lock version, as it was easily recognised by the enemy. Later in the war, cheaper cardboard suitcases were used instead.

Louis Meulstee's excellent book Wireless for the Warrior, volume 4 even shows an example of a wooden carpenter's toolbox in which a B2 is fitted. The dimensions of the suitcase are pretty standard for the era. This B2 in it's original issue simulated leather cardboard covered wood frame suitcase with 3 locks. The cases were changed later in the war for twin catched cases, as three, one lock and two catches, became too identifiable by the Gestapo.

A photograph in the gallery was taken during WWII, probably in 1942 or 1943, and shows this B2 radio's production line at the Bontex Knitting Mills, which became SOE Station VIIa (7a) . This facility is also known as Stonebridge Park,

While Virgina Hall {see her photo in the gallery} was adept in all aspects of tradecraft, one of the most powerful tools at her disposal was the suitcase radio, a catch-all term used to describe any transceiver small enough to be transported into the field and operated covertly. A suitcase was often used to house the radio as it would be less likely to arouse suspicion if the spy’s lair was discovered. The B2 suitcase radio was also a great form factor for a portable transceiver – just the right size for the miniaturized radios of the day, good operational ergonomics, and perfect for quick setup and teardown. You can even imagine a spy minimally obfuscating the suitcase’s real purpose with a thin layer of folded clothing packed over the radio.

Great care was given to ensure that the field agent would have every chance of using the radio successfully and that it would operate as long as possible under adverse conditions. With a power budget often limited to five watts or so, these radios were strictly QRP affairs. Almost every suitcase rig operated on the high-frequency bands between 3 MHz and 30 MHz, to take advantage of ionospheric skip and other forms of propagation. An antenna optimized for these bands would likely be a calling card to the enemy, especially in an urban setting, so controls were provided to tune almost any length of wire into a decent antenna.

Footnote; it is estimated around 7,000 of this form of clandestine spy-craft equipment were made by the British. It’s historical WW2 Nazi equivalent, the German made Enigma Machine, over 100,000 of those were manufactured, almost 15 times as many. Yet, surviving examples of the Enigma Machine can now achieve between $250,000 to $800,000. Thus, it is entirely possible that these suitcase transceivers can one day approach these figures, if not even likely. In fact in almost all respects they should be on a value parity already, as the operators of the Enigmas were based in relatively comfortable German bases, ships or field commands. Safe and relatively well protected and far away from fear and terror. The operators of these transceivers, men and women, many barely out of their teenage years, were, every single minute of every single day at appalling risk of capture and the inevitable, unspeakable torture {especially the women}, at the hands of the Gestapo, and summary execution, after being transferred to a concentration camp, sometimes simply within a few weeks of the start of their clandestine service in Nazi occupied Europe.

A dear friend of the partners {Mark and David's} late mother, Camilla Hawkins, was Anita Vulliamy, daughter in law of Major-General C.H.H. Vulliamy. She was a simply a remarkable lady, who, during the war, was captured by the Gestapo, horrifyingly tortured, but managed to survive captivity. During her months in the Gestapo prison she crocheted a holy cross, made of prison cell straw bedding. After the war, her cross was exhibited alongside a similar piece, a straw doll, made by British SOE heroine Odette Churchill at a Charity event in London in 1956 and they raised £875 for the Polio Fund in one week. A huge sum in those days. Camilla mentioned that her friend, Anita, almost always wore fine leather gloves in company, as her finger nails had been torn out by her Gestapo interrogators. They grew back in part, but not well enough for Anita to feel comfortable to show her hands in public. Anita and Odette survived, and both considered themselves to be the extraordinarily lucky ones.

Code: 25249