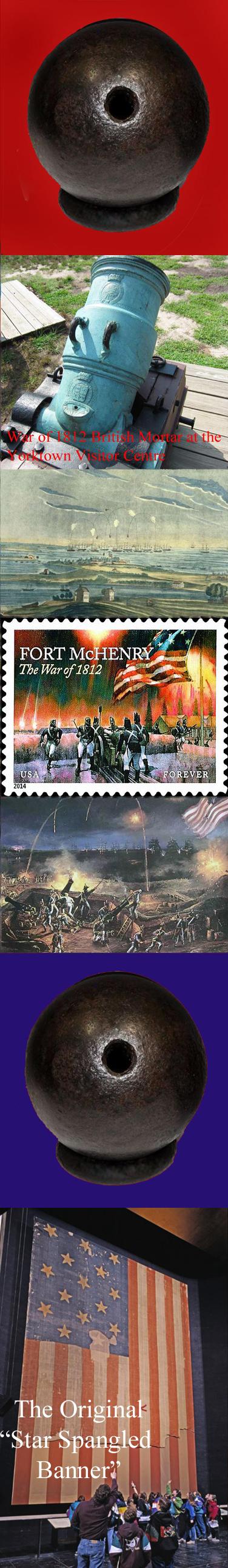

A Fabulous, Rare Early 19th Cent. British Explosive 10" Mortar Bomb From the War of 1812 In America. Likely, Fomerly Part of The Armament of HMS Terror, During The Bombardment of Fort McHenry in Baltimore. The Battle Site of “The Star Spangled Banner”

One of four exceptionally rare 10" Royal Naval mortar balls we are delighted to have acquired from our private historical Royal Naval collector in Plymouth, the same city where Admiral Cochrane, fleet commander at the attack on Fort McHenry, became Commander-in-Chief of the naval base in Plymouth, England, after the war of 1812.

They were apparently unloaded from ships of the line from Admiral Cochrane's returning fleet, with Commander John Sheridan of HMS Terror, supposedly in Plymouth, during the war of 1812 and the 90 pound bronze mortars were removed from his fleet. They are all in a very good state of preservation but with differing amounts of surface russetting. It is said the Admiral and his crew loathed and feared these particular huge mortars due to their likely hood of miss-fire. The 90 pounder shell had to be first primed, and then lit, before it entered the muzzle of the bronze cannon, that had previously been loaded with pounds of gunpowder, the cannon mortar was then lit and fired which thus ejected, with a massive force explosion, the explosive ball high into the sky to the centre of the enemy's ranks. However, the shell might have accidentally exploded while it was being manouvered, it might also have ignited the powder within the breech of the cannon, or, the fizzing mortar might have not have been ejected at all due to a cannon miss-fire. Any one of these horrifying events would be catastrophic, and the resulting explosion would be of of such magnitude it would likely have killed most on board, and probably sunk the vessel entirely with all hands. This a series of events that any ships captain or admiral would not consider to be entirely advantageous

The previous two 10” mortar bombs, that we had two years ago, were the very first we had had in 50 years. The first of those two we sold to an esteemed private museum in Florida USA, the other to an American private collector

We are not expecting ever to see any more of their like again. It would make a fabulous and impressive historical display piece of significant and particular Royal Naval and early American history interest

These 10" mortars explosive balls were fired by the 10" mortars used by Admiral Cochrane's fleet {with Commander John Sheridan aboard HMS Terror} against Fort McHenry, Baltimore Harbour, September 12–14, 1814, and the resulting 10" mortar bomb shell's mid air explosions, against the backdrop of the US flag flying at Fort McHenry, Baltimore Harbour, inspired the patriotic anthem, the

"Star Spangled Banner".

It was the sight of these very 10" mortar bombshells, that originally weighed around 90 pounds each, including powder therein, that when they exploded over Fort McHenry in Harbour, it inspired Francis Scott Key to write his poem that became the US anthem.

Naturally, this is a perfectly intact surviving example, and one of the 10" mortar shells that either wasn't fired, or, failed to explode.

With Washington in ruins, the British next set their sights on Baltimore, then America’s third-largest city. Moving up the Chesapeake Bay to the mouth of the Patapsco River, they plotted a joint attack on Baltimore by land and water. On the morning of September 12, General Ross’s troops landed at North Point, Maryland, and progressed towards the city. They soon encountered the American forward line, part of an extensive network of defences established around Baltimore in anticipation of the British assault. During the skirmish with American troops, General Ross, so successful in the attack on Washington, was killed by a sharpshooter. Surprised by the strength of the American defences, British forces camped on the battlefield and waited for nightfall on September 13, 1814, planning to attempt another attack under cover of darkness.

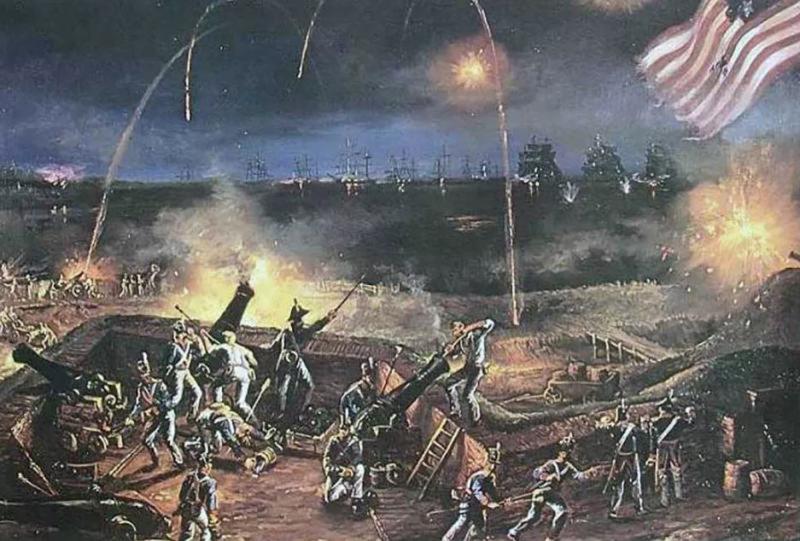

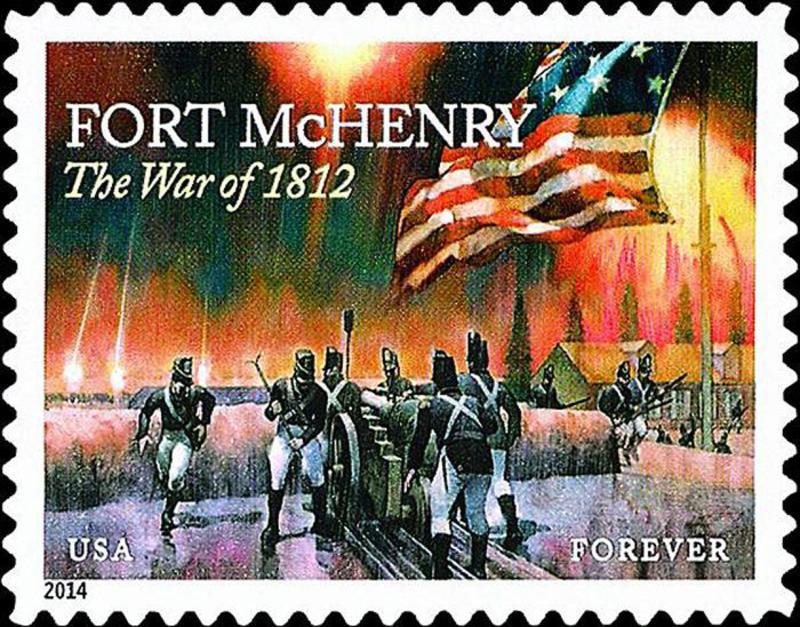

Meanwhile, Britain’s naval force, buoyed by its earlier successful attack on Alexandria, Virginia, was poised to strike Fort McHenry and enter Baltimore Harbour. At 6:30 AM on September 13, 1814, Admiral Cochrane’s ships began a 25-hour bombardment of the fort. Rockets whistled through the air and burst into flame wherever they struck. Mortars fired 10- and 13-inch bombshells that exploded overhead in showers of fiery shrapnel. It is said many exploded too soon as the fuses were set too short, which created the firework effect. Major Armistead, commander of Fort McHenry and its defending force of one thousand troops, ordered his men to return fire, but their guns couldn’t reach the enemy’s ships. When British ships advanced on the afternoon of the 13th, however, American gunners badly damaged them, forcing them to pull back out of range. All through the night, Armistead’s men continued to hold the fort, refusing to surrender. That night British attempts at a diversionary attack also failed, and by dawn they had given up hope of taking the city. At 7:30 on the morning of September 14, Admiral Cochrane called an end to the bombardment, and the British fleet withdrew. The successful defense of Baltimore marked a turning point in the War of 1812. Three months later, on December 24, 1814, the Treaty of Ghent formally ended the war. "The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British ships of the Royal Navy in Baltimore Harbour during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. Key was inspired by the large U.S. flag, with 15 stars and 15 stripes, known as the Star-Spangled Banner, flying triumphantly above the fort during the U.S. victory. During the bombardment, HMS Terror and HMS Meteor provided some of the "bombs bursting in air".

The 15-star, 15-stripe "Star-Spangled Banner" that inspired the poem

Key was inspired by the U.S. victory and the sight of the large U.S. flag flying triumphantly above the fort. This flag, with fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, had been made by Mary Young Pickersgill together with other workers in her home on Baltimore's Pratt Street. The flag later came to be known as the Star-Spangled Banner, and is today on display in the National Museum of American History, a treasure of the Smithsonian Institution. It was restored in 1914 by Amelia Fowler, and again in 1998 as part of an ongoing conservation program. Pictures in the gallery of the siege from contemporary paintings and engravings, a commemorative stamp issued in 2014, and an original War of 1812 bronze British mortar now kept at Yorktown Visitor Centre, and a photo of the flag in the National Museum of American History, 1989. The original flag that was illuminated by these very 10" mortar shells.

Sir Alexander Cochrane was born into a Scottish aristocratic family as a younger son, and like many in this position made a career out of military service. Cochrane joined the Royal Navy as a boy and fought in the American Revolution. Following this war he rose quickly in the Napoleonic Wars, earning renown in the Battle of San Domingo and the Conquest of Martinique in 1809.

By the beginning of the War of 1812, Cochrane was a well-seasoned and high-ranking officer. As a vice admiral, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the new North American naval station in Bermuda. He devised a clever plan to weaken the American defenses and turn America’s slaves against the country by inviting any American – slave or free – to join the British Navy. Many slaves took this offer, escaping to British lines for military service in exchange for their freedom.

By the summer of 1814, Cochrane had returned to the waters of the United States, overseeing the raids of the Chesapeake. Lieutenant General Sir George Prevost, governor of Upper Canada, suggested launching an invasion somewhere in the United States in retaliation against the sack of York and to weaken the American forces, relieving pressure on Canada. Cochrane landed the ground troops to invade Washington, and presided over the bombardment of Fort McHenry in the Battle of Baltimore.

After only moderate success in the Chesapeake, Cochrane wanted to push toward New Orleans in order to cement the British position in the United States. He orchestrated an amphibious attack on the city via Lake Borgne, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico that could bring troops close to the city.

Although Cochrane was successful in the Battle of Lake Borgne, allowing the British Army to advance toward New Orleans, the disastrous defeat at the Battle of New Orleans damaged his reputation. The influential Napoleonic War hero the Duke of Wellington in particular blamed Cochrane of the death of his brother-in-law, Sir Edward Michael Pakenham, the British general overseeing land troops at the Battle of New Orleans.

However, despite the criticisms and ultimate failure to get a foothold in the United States, Cochrane was promoted to admiral after the war, and served out the rest of his military career as Commander-in-Chief of the naval base in Plymouth, England.

The fictional nautical adventures of Captain Horatio Hornblower were supposedly based on Cochrane’s notable maritime achievements.

HMS Terror had a most remarkable later history, alongside HMS Erebus

Franklin's lost expedition was a failed British voyage of Arctic exploration led by Captain Sir John Franklin that departed England in 1845 aboard two ships, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, and was assigned to traverse the last un-navigated sections of the Northwest Passage in the Canadian Arctic and to record magnetic data to help determine whether a better understanding could aid navigation.The expedition met with disaster after both ships and their crews, a total of 129 officers and men, became icebound in Victoria Strait near King William Island in what is today the Canadian territory of Nunavut. After being icebound for more than a year, Erebus and Terror were abandoned in April 1848, by which point two dozen men, including Franklin, had died. The survivors, now led by Franklin's second-in-command, Francis Crozier, and Erebus's captain, James Fitzjames, set out for the Canadian mainland and disappeared, presumably having perished

The mortar is empty, inert and completely safe.

The mortar is empty, inert and completely safe. Seated on an old iron ring for the photograph, not included with the mortar

Code: 25058

1650.00 GBP