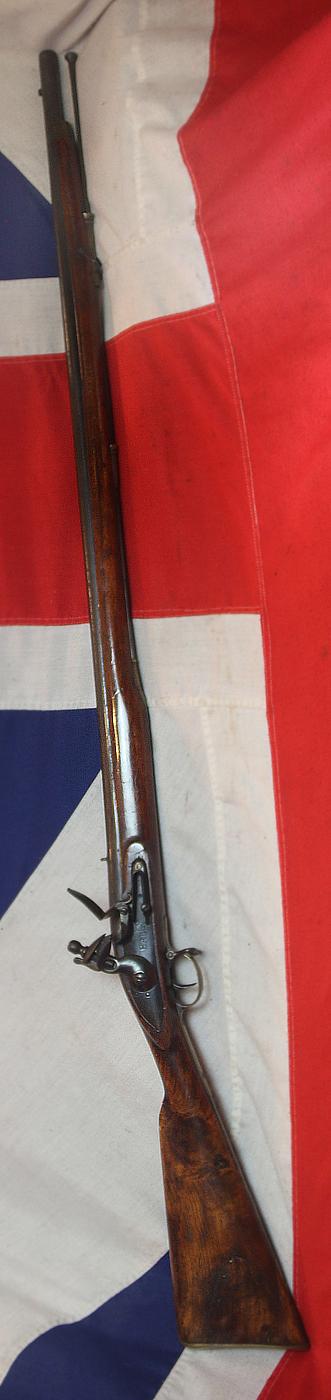

An Early 19th Century Infantryman Volunteer's 'Brown Bess' Musket, In Super Condition

With excellent walnut rail stock, very good and tight crisp action, regulation brass mounts and ramrod, with twin steel sling swivels, all original and all present. Likely EIC, with good barrel with bayonet lug and rear sight. Ring neck cock flintlock, maker marked.

The Brown Bess musket was the standard weapon of the British infantry for more than a century. Soldiers on both sides of the War of 1812 employed it in battle, staring down its barrel at opponents across distances of less than a hundred yards.

Flintlock musket

The Brown Bess musket was the standard weapon of the British for more than a century.

British foot soldiers marched into battle with this musket—nicknamed “Brown Bess”—for more than 100 years. British redcoats used the Brown Bess to fight the War of Independence in the colonies, and many of their opponents in the Americans’ Continental army used it as well. British soldiers fighting in the Napoleonic wars carried it into battle, and it was the principal firearm used by the infantrymen who fought the War of 1812.

The Brown Bess had several distinctive features. It was a large-calibre weapon: the bullet it fired was a lead ball from .65 to up to three-quarters of an inch in diameter, three times the diameter of a modern .22-calibre rifle round. The inside of its barrel was smooth: unlike more accurate “rifled” muskets used by the famous rifle regiments, the Brown Bess had a smooth bore with no grooves to make its fire more accurate. Soldiers loaded the musket through the muzzle, which meant that each bullet had to be forced down a longer than three foot barrel before firing. Even trained soldiers could only launch two or three shots per minute.

Because the weapon was slow to load and relatively inaccurate (experienced soldiers generally estimated its range between 50 and 100 yards), armies developed tactics that helped compensate for its shortcomings. The limitations of smoothbore muskets like the Brown Bess forced units employ “linear tactics,” in which a hundreds of soldiers stood in neat lines, shoulder-to-shoulder and out in the open. While such tactics appear decidedly unstealthy to twenty-first century eyes, they proved essential on the battlefields of all the conflicts which Britain was involved.

There, stealth was a low priority. Packing the men into blocs allowed officers to coordinate their troops’ fire into synchronized volleys. Firing a hundred guns in the same direction at once helped ensure that at least some, often most of the inaccurate musket balls found their targets. And grouping the men into neat lines out in the open helped commanders ensure that few of their troops gave in to the natural instinct to flee.

Of course, packing troops into blocks and fighting in the open required tremendous discipline from the individual soldiers. Infantrymen had to stand exposed to enemy fire as they loaded and fired their own muskets. And in some situations, soldiers learned the grisly dangers of fighting in lines—as at the Battle of New Orleans in the 1812 war, where American artillery attacked the exposed British formations with devastating effect. Small contemporary wooden field repair at the base of the buttplate

40" barrel .65 calibre

Code: 24875

Price

on

Request