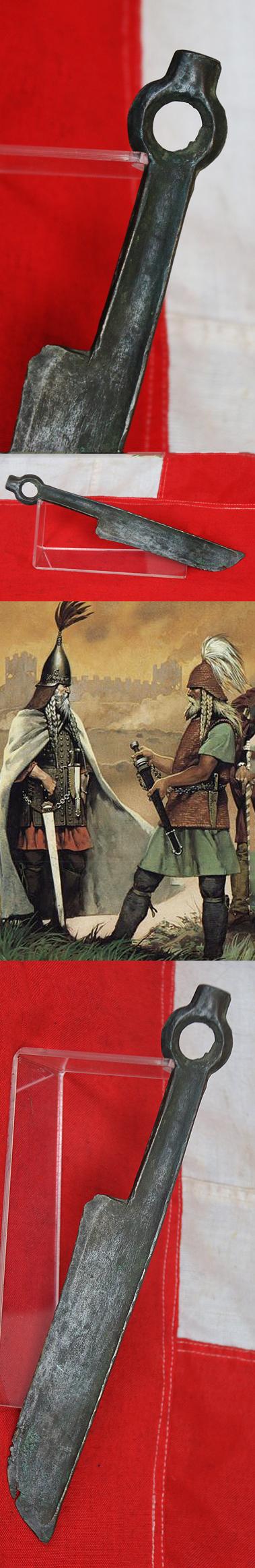

A Most Rare Bronze Age 'Celtic' Ring Dagger Knife Around 2500 Years Old. In Superb Excavated Condition.

A mid-European cast bronze knife. The blade is formed as a curved casting, thickening towards the outside of the curve, and with an edge to the inside. The handle has a depression on each side with a ring pommel typical of the ancient celts. It is particularly rare in that most Celtic ring knives found in the past 250 years have been Iron Age examples, certainly the ones we have had in the past 30 years have been so, thus this being bronze, although made in the Iron Age, makes it a most scarce knife.

From a collection of antiquities, swords daggers, and rings, that arrived , many pieces sold for the part benefit of the Westminster Abbey fund, and the Metropolitan Museum fund

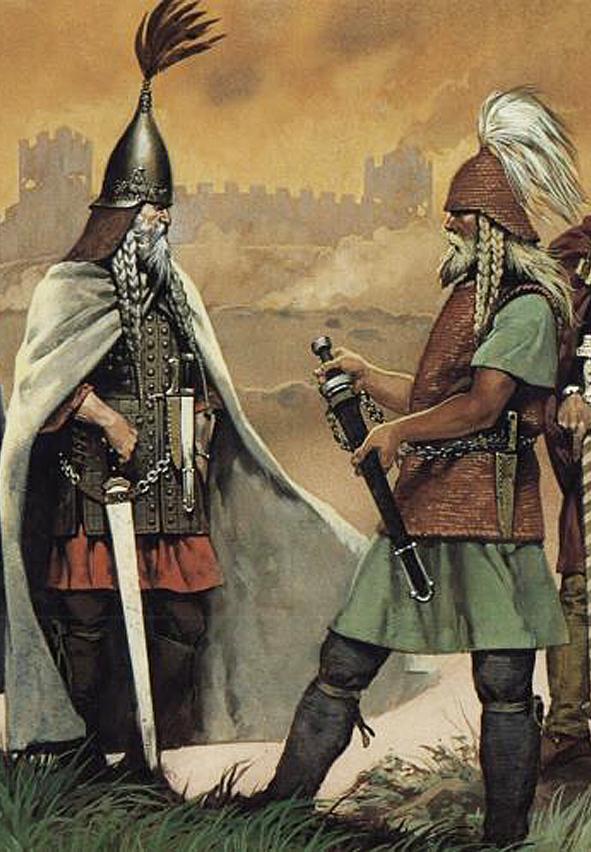

the ancient Celtic tribes are far too often overlooked in favour of Romans and Vikings and Anglo-Saxons, their stories stripped away to Boudicca, the Iceni and failed revolt.

Yet the reality was rather more complex, with the ultimately victorious Romans deliberately misrepresenting the Celts as noble savages in order to provide a contrast with “the idea of Rome as a disciplined, ordered, civilising presence”. History might well be written by the victors

The Romans seem to have used the term “Celt” very similarly to how the Greeks used it. They applied the term to a large collection of tribes covering huge portions of western Europe. All the Gallic tribes — the tribes of Gaul — were called Celts by the Romans. We clearly see this in Julius Caesar’s De Bello Gallico (1.1):

“All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in ours Gauls, the third.”

But beyond just using the term “Celts” to refer to the Gallic tribes, other Roman writings show that they also used the term to refer to some of the inhabitants of Iberia. For example, Strabo (3.4.5) refers to Celts in that region who became the Celtiberians and the Berones. Many other tribes in Iberia were also considered to be Celtic. In other words, we see that the Romans considered the Celts to cover several large portions of Western Europe. This is consistent with Greek description of the Celts being the single most notable people to the west.

It is important to note that the material culture of the Celtiberians was very different from the material culture of the Gallic Celts. This being so, it is evident that archaeology cannot determine which nation was or was not Celtic. It is evidently not the style of artwork or design of houses or type of pottery that determines whether one is or is not a Celt. Regarding genetics, there does not appear to be any evidence of large-scale migration from Gaul to Iberia. Yet, that does not stop the Celts of Iberia from being considered Celts, either in ancient or modern sources.

On the other hand, the genetics of the population of England is known to be primarily made up of genes from the pre-Saxon inhabitants. Yet despite that, no one would call the English a “Brythonic” nation. So it does not seem very useful to use genetics as the main criterion for determining whether a nation was or was not Celtic.

Therefore, using language as the main basis for determining that ancient populations of Europe does seem to be the most useful method, even if it is not perfect. On this basis, it is very reasonable indeed to refer to the Britons as “Celts”.

Part of the proceeds of this piece were to benefit the Acquisition Fund of the Arms and Armor department, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Overall 11 inches long, blade 6 3/4 inches

Code: 24841

875.00 GBP