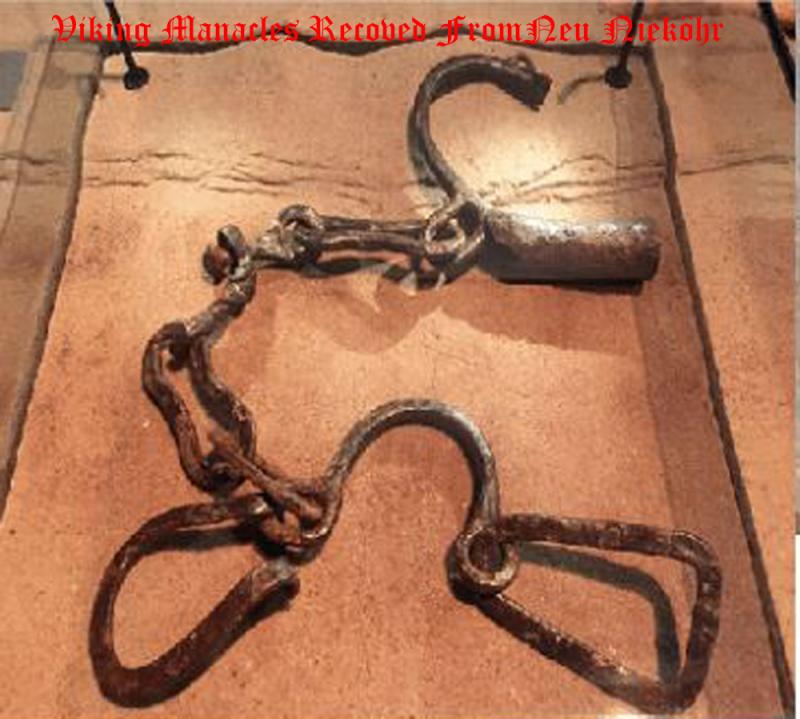

Very Rare Original Viking Prisoner Shackles. Near Identical to a Viking Set Discovered in a Former Viking Town Neu Nieköhr, Germany

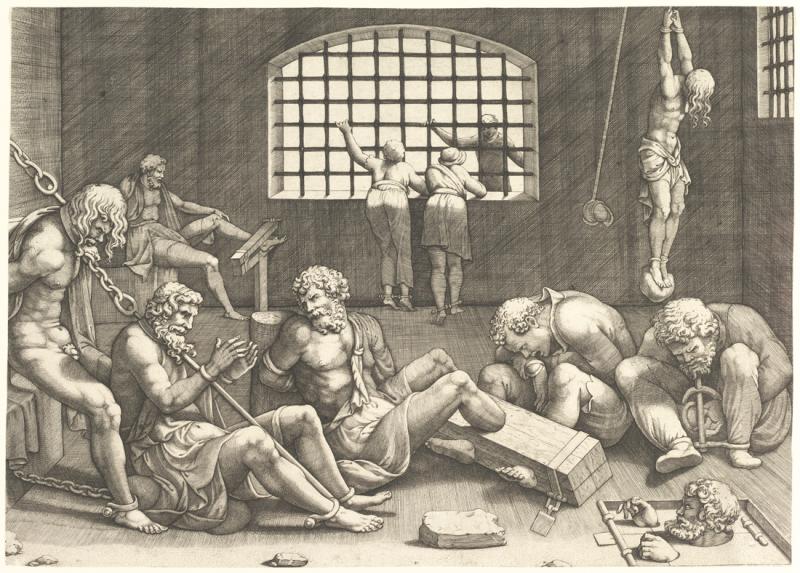

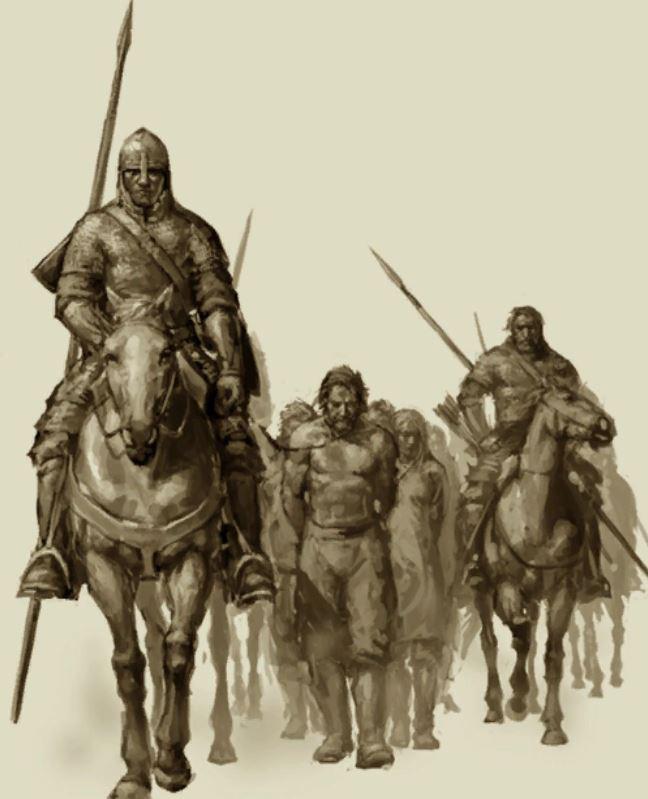

Viking prisoners, encased in these shackles, and captured, were especially taken from England and many from Ireland

Many of those captives taken in western Europe, especially the British Isles, their eventual destination might have been the Norse colonies of the North Atlantic. Others might have been taken to the Continent; in 1047, for example, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records a Viking raiding fleet as selling a

cargo of English captives in Flanders before sailing home. It is also possible that captives were taken to Scandinavia in order to be sold or exploited among their captors’ communities, as suggested by the lives of Anskar and Rimbert, which mention captives living in and being transported through the major market centres of Birka, Neu Nieköhr, and Hedeby during the ninth century.

In Laxdæla saga, we similarly find a number of women, including an Irish captive named Melkorka, being sold by a Viking Rūs trader at a market associated with a public assembly in the Brenno Islands.

Evidence for the long-distance trafficking of captives along the eastern trade routes of the Viking world is provided by numerous sources, including the tenth-century Byzantine source, De Administrando Imperio, which describes Viking Rūs merchants transporting captives by boat along the Dniepr river. Also of note is the famous account of the Arabic diplomat Ahmad ibn Fadlān, who encountered a group of Viking Rūs slavers and a number of female captives on the Volga river in 922.

While written sources provide a relative wealth of information on captive taking

and sale during the Viking Age, slaving is often considered to be an archaeologically ‘invisible’ practice. As such, it is not surprising that the material record allows only fragmentary insights into this activity. Perhaps the most evocative evidence for slave trading is a corpus of what appear to be iron shackles and collars, most of which have been recovered during excavations at urban centres thought to be associated with the slave trade, such as Dublin, Birka, and Hedeby

For refe see; Ben Raffield (2019): The slave markets of the Viking world:

comparative perspectives on an ‘invisible archaeology’, Slavery & Abolition,

Code: 24791