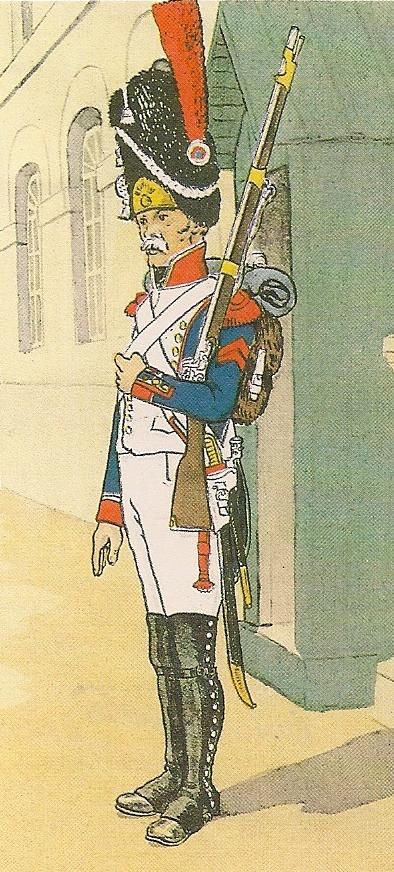

A Most Scarce and Desirable, French, 1767 to the Napoleonic Wars Period, French Grenadier of Infantry Sword

Used from the revolution right through the Napoleonic Wars by French grenadiers.

With brass hilt and steel blade. A scarce sword from a most turbulent era of French history. Used from the era of France's alliance to America in the Revolutionary War of 1777, right through the French Revolution 1792, and then in the Napoleonic Wars till 1815.

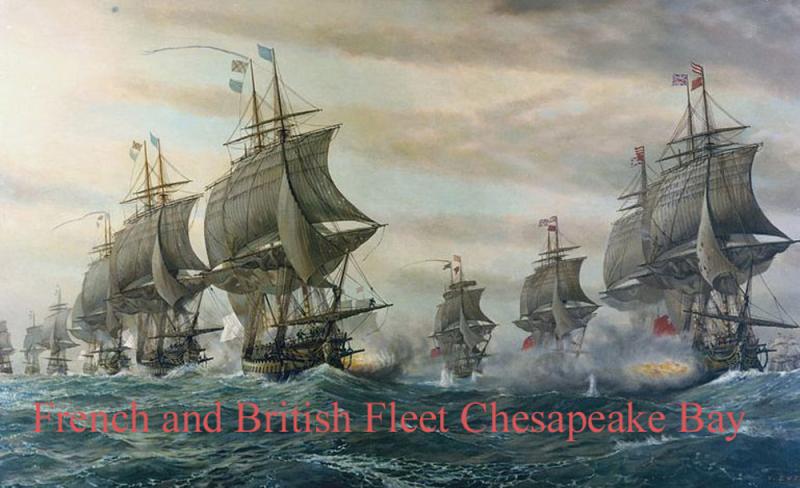

There are several such swords in Smithsonian in America. French participation in North America was initially maritime in nature and marked by some indecision on the part of its military leaders. In 1778 American and French planners organized an attempt to capture Newport, Rhode Island, then under British occupation. The attempt failed, in part because Admiral d'Estaing did not land French troops prior to sailing out of Narragansett Bay to meet the British fleet, and then sailed for Boston after his fleet was damaged in a storm. In 1779, d'Estaing again led his fleet to North America for joint operations, this time against British-held Savannah, Georgia. About 3,000 French joined with 2,000 Americans in the Siege of Savannah, in which a naval bombardment was unsuccessful, and then an attempted assault of the entrenched British position was repulsed with heavy losses.

Support became more notable when in 1780; 6,000 soldiers led by Rochambeau were landed at Newport, abandoned in 1779 by the British, and they established a naval base there. Rochambeau and Washington met at Wethersfield, Connecticut in May 1781 to discuss their options. Washington wanted to drive the British from New York City, and the British force in Virginia, led first by turncoat Benedict Arnold, then by Brigadier William Phillips, and eventually by Charles Cornwallis, was also seen as a potent threat that could be fought with naval assistance. These two options were dispatched to the Caribbean along with the requested pilots; Rochambeau, in a separate letter, urged de Grasse to come to the Chesapeake Bay for operations in Virginia. Following the Wethersfield conference, Rochambeau moved his army to White Plains, New York and placed his command under Washington.

De Grasse received these letters in July, at roughly the same time Cornwallis was preparing to occupy Yorktown, Virginia. De Grasse concurred with Rochambeau, and sent back a dispatch indicating that he would reach the Chesapeake at the end of August, but that agreements with the Spanish meant he could only stay until mid-October. The arrival of his dispatches prompted the Franco-American army to begin a march for Virginia. De Grasse reached the Chesapeake as planned, and disembarked troops to assist Lafayette's army in the blockade of Cornwallis. The arrival of a British fleet sent to dispute de Grasse's control of the Chesapeake was defeated on September 5 at the Battle of the Chesapeake, and the Newport fleet delivered the French siege train to complete the allied military arrival. The Siege of Yorktown and following surrender by Cornwallis on October 19 were decisive in ending major hostilities in North America.Starting with the Siege of Yorktown, Benjamin Franklin never informed France of the secret negotiations that took place directly between Britain and the United States. Britain relinquished her rule over the Thirteen Colonies and granted them all the land south of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi River. However, since France was not included in the American-British peace discussions, the alliance between France and the colonies was broken. Thus the influence of France and Spain in future negotiations was limited. Last photo in the gallery is of the depiction of the Second Battle of the Virginia Capes (Battle of the Chesapeake).

Code: 24437

695.00 GBP