An Imperial Roman 2nd Century Bronze Ring, Excellent Condition and Still Wearable Today

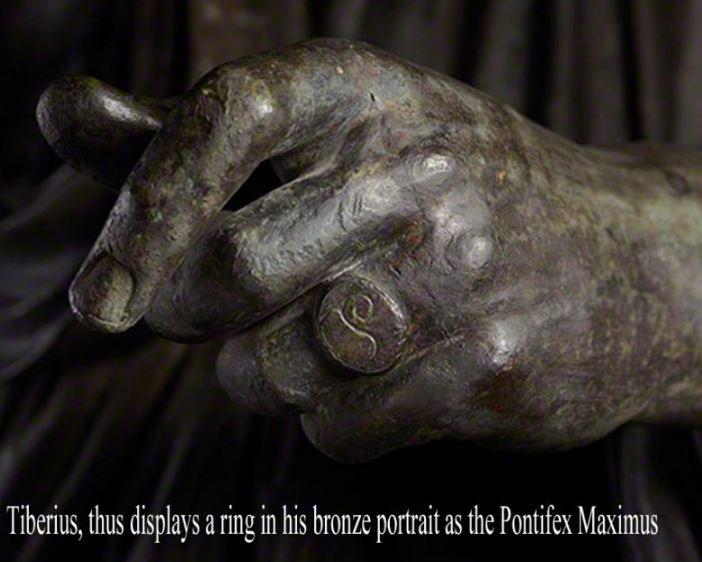

The same size, shape and form of unadorned ring worn by two of the Imperial Ceaser's, both Augustus and Tiberius. Part of a superb original museum grade collection we have acquired of Roman rings, also with some medieval and Norman rings as well. They are both clearly wearing their identical size and shaped rings on both of the surviving original Roman bronze statues of the emperors. Augustus Caeser and Tiberius Caeser both wore that ring type, engraved with the the symbol of a lituus, the mark of a Roman Augur a type of sorcerer. Augustus Caeser was indeed an auger himself, as was Pompey. The complete Roman Empire had around a 60 million population and a census more perfect than many parts of the world (to collect taxes, of course) but identification was still quite difficult and aggravated even more because there were a maximum of 17 men names and the women received the name of the family in feminine and a number (Prima for First, Secunda for Second…). A lot of people had the same exact name.

So the Roman proved the citizenship by inscribing themselves (or the slaves when they freed them) in the census, usually accompanied with two witnesses. Roman inscribed in the census were citizens and used an iron or bronze ring to prove it. With Augustus, those that could prove a wealth of more than 400,000 sesterces were part of a privileged class called Equites (knights) that came from the original nobles that could afford a horse. The Equites were middle-high class and wore a bronze or gold ring to prove it, with the famous Angusticlavia (a tunic with an expensive red-purple twin line). Senators (those with a wealth of more than 1,000,000 sesterces) also used the gold ring and the Laticlave, a broad band of purple in the tunic.

So the rings were very important to tell from a glimpse of eye if a traveller was a citizen, an equites or a senator, or legionary. People sealed and signed letters with the rings and its falsification could bring death.

The fugitive slaves didn’t have rings but iron collars with texts like “If found, return me to X” which also helped to recognize them. The domesticus slaves (the ones that lived in houses) didn’t wore the collar but sometimes were marked. A ring discovered 50 years ago is now believed to possibly be the ring of Pontius Pilate himself, and it was the same copper-bronze form ring as is this one. Classified as Guiraud type 4. Guiraud Ring Types A categorisation of 1st to 5th century ce Roman and provincial Gallo-Roman ring types devised by the 20th century French scholar Hélène Guiraud.

Like many of our selection of antiquities, many originally arrived in England as souvenirs of a Grand Tour, from around 200 years ago,

Richard Lassels, an expatriate Roman Catholic priest, first used the phrase “Grand Tour” in his 1670 book Voyage to Italy, published posthumously in Paris in 1670. In its introduction, Lassels listed four areas in which travel furnished "an accomplished, consummate traveler" with opportunities to experience first hand the intellectual, the social, the ethical, and the political life of the Continent.

The English gentry of the 17th century believed that what a person knew came from the physical stimuli to which he or she has been exposed. Thus, being on-site and seeing famous works of art and history was an all important part of the Grand Tour. So most Grand Tourists spent the majority of their time visiting museums and historic sites.

Once young men began embarking on these journeys, additional guidebooks and tour guides began to appear to meet the needs of the 20-something male and female travelers and their tutors traveling a standard European itinerary. They carried letters of reference and introduction with them as they departed from southern England, enabling them to access money and invitations along the way.

With nearly unlimited funds, aristocratic connections and months or years to roam, these wealthy young tourists commissioned paintings, perfected their language skills and mingled with the upper crust of the Continent.

The wealthy believed the primary value of the Grand Tour lay in the exposure both to classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and to the aristocratic and fashionably polite society of the European continent. In addition, it provided the only opportunity to view specific works of art, and possibly the only chance to hear certain music. A Grand Tour could last from several months to several years. The youthful Grand Tourists usually traveled in the company of a Cicerone, a knowledgeable guide or tutor.

The ‘Grand Tour’ era of classical acquisitions from history existed up to around the 1850’s, and extended around the whole of Europe, Egypt, the Ottoman Empire, and the Holy Land.

Code: 24363